Congratulations on being awarded the National Science Foundation (NSF) Graduate Research Fellowship (GRF) (or a similar remunerative, competitive, national fellowship)! Whether you’re a prospective grad student or a current first- or second-year PhD student, this fellowship is a great boon to your research, your CV, and almost certainly your finances. However, you may not yet realize that your finances will become a bit tricky once you start receiving your fellowship. With the help of this article, you can avoid the pitfalls associated with fellowship income and fully capitalize on the benefits.

Further listening: The Financial and Career Opportunities Available to National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellows

The NSF GRFP’s Negotiation Power

I’m sure you didn’t miss this headline info about the NSF GRFP: The fellowship pays you a stipend of $34,000 plus $12,000 of educational expenses to your institution for three years. Awesome! At the majority of universities in the US, that stipend amount is well above what you would be paid if you didn’t receive the fellowship, so you’ve effectively achieved a raise for the next three years.

But the good news doesn’t stop there: Your university/department might confer even more benefits upon you for winning independent funding. If the administration isn’t forthcoming about these additional benefits, it is appropriate to inquire about them.

Independence

Your new outside funding may give you a degree of independence in your research that you wouldn’t otherwise enjoy. This is highly dependent on your field, department, and advisor, but the fellowship may enable you to take your doctoral research in a direction that you advisor couldn’t or wouldn’t have supported without it. Perhaps you could take a risk on a side project, establish a new collaboration, or take extra time to rotate through a lab to gain new skills.

Additional Funding

At many universities, there is a standard offer of additional funding for winning a multi-year, lucrative fellowship like the NSF. This offer could come in one or more forms, such as:

- A guarantee of funding for additional years

- A one-time bonus

- A stipend supplement above $34,000 while you have the fellowship

- A stipend supplement after the fellowship concludes (e.g., up to $34,000/year for your remaining time in graduate school)

Not all departments offer additional funding to NSF GRFP recipients, but it’s worth inquiring about with your advisor, the administration, and current NSF fellows at your university. Stipend supplements during the time that you receive the NSF GRF are more common in high cost-of-living cities where the departmental base stipend is near $34,000/year to begin with. For example, searching “NSF” in the PhD Stipends database reveals stipend supplements awarded during the NSF GRFP years to students at the University of California at Berkeley, Northwestern University, and Columbia University, while a student at the University of California at San Diego writes that he/she received no funding incentive for winning the NSF GRF.

For Prospective Graduate Students

You’ll never have more negotiation power than you do as a prospective graduate student with an outside fellowship in hand. Unfortunately, you don’t have a lot of time to negotiate as the NSF GRFP awards list comes out approximately two weeks before grad school decision day, April 15.

Further reading: Vote with Your Feet, Prospective Graduate Students

As quickly as possible, you need to clarify if the offers from the universities you are still considering are going to be sweetened at all now that you have your fellowship. If the financial package from your preferred university isn’t up to par with your other offers (after considering cost of living differences), you can tactfully ask if a bonus, stipend supplement, or guarantee of future funding is possible.

Join Our Phinancially Distinct Community

Receive 1-2 emails per week to help you take the next step with your finances.

Budgeting with Your Fellowship Income

There are two vital questions you need to ask of your department before you can begin creating a budget for your NSF GRF stipend.

- After the fellowship ends, what will my stipend be?

- How frequently is my fellowship disbursed?

Accelerate Progress on Financial Goals

In my ideal personal finance-oriented world, an NSF fellow would live on (less than) the base stipend from his department and put all the excess income received toward growing his wealth. There are a few advantages to that approach:

- Your lifestyle roughly matches that of your peers in your department.

- You can relatively quickly achieve financial goals such as saving or debt repayment.

- If your income is set to drop once the fellowship ends, you avoid acclimation to the higher, temporary income and don’t have to make major lifestyle sacrifices once the three years are up.

Some financial goals you could work on during the time you receive the additional fellowship funds are:

- Eliminating any troublesome debt (e.g., credit card balances, medical debt, car loan)

- Saving up cash for short-term needs and expenses (e.g., emergency fund, targeted savings accounts)

- Investing for long- and mid-term goals (e.g., retirement, house down payment)

- Pay down student loans

Further reading:

- Options for Paying Down Debt during Grad School

- Why Every Grad Student Should Have a $1,000 Emergency Fund

- Targeted Savings Accounts for Irregular Expenses

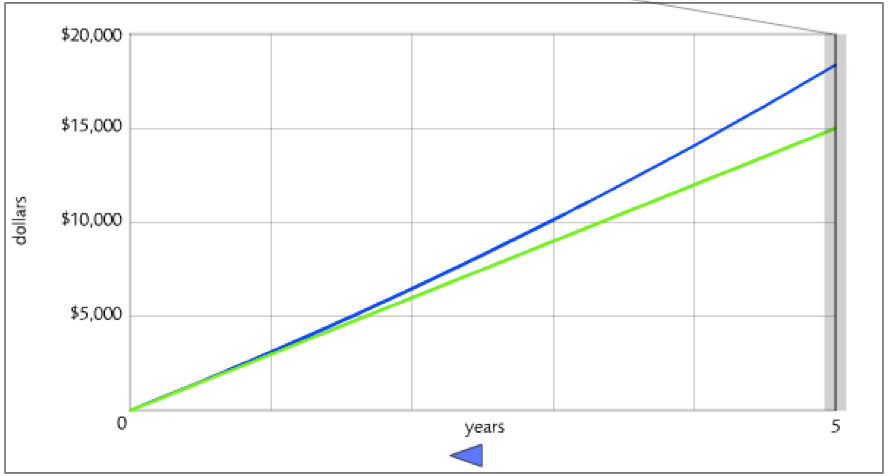

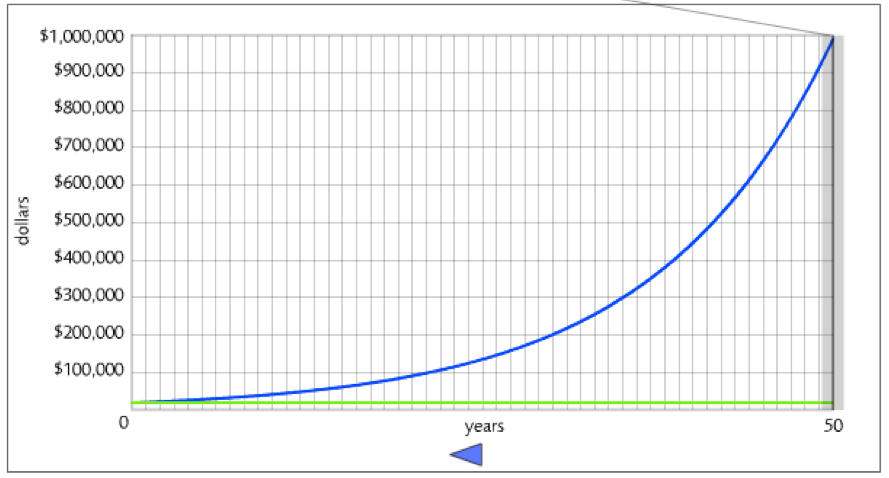

- Whether You Save during Grad School Can Have a $1,000,000 Effect on Your Retirement

- Why the Roth IRA Is the Ideal Long-Term Savings Vehicle for a Grad Student

- Why Pay Down Your Student Loans in Grad School

This strategy is easiest to implement for graduate students who start the NSF GRF after one or more years in grad school. Just put all of your ‘raise’ toward financial goals and don’t change anything about your lifestyle! Prospective grad students will have to be more conscious about setting up their grad student lifestyle on a lower income than they will start out with.

Preparing for the Post-Fellowship Income Drop

If you choose to upgrade your lifestyle with your fellowship stipend, be careful to maintain any long-term financial contracts at a level that will be sustainable for you after your income drops (if it will). The two key areas to watch out for are housing and transportation expenses. While it is possible to reduce your spending in either of these areas during grad school, it is a painful process, so it is preferable to lock in your spending in those areas at a level that you can maintain long-term.

Budgeting with an Irregular Income

Sometimes, fellowships are disbursed to the recipient at a frequency other than monthly, e.g., once per term. This schedule can cause issues for budgeting, which is usually framed as turning over each month.

One of the advantages of an infrequent disbursement schedule is that you are paid at the beginning of the period rather than the end, so the money you need throughout the period is already available to you. However, you may not be able/inclined to use typical budgeting software functions and prefer to set up your own budgeting system.

One of the most useful budgeting concepts for people with irregular incomes is that of fixed vs. variable expenses. At the beginning of your budgeting period, project the fixed expenses that will be paid during the period, such as your rent/mortgage, debt payments, certain utilities, subscriptions, etc. Then allocate your remaining income to your variable expenses at a frequency that is convenient for you. For example, you can estimate the variable utility bills that you may pay monthly during the period, plan to spend no more than a certain amount of money each week on groceries, and give yourself a lump sum of money for entertainment for the entire period to be spent as opportunities arise. In this way, allocate your fellowship disbursement so that you are sure that your expenses won’t exceed your income (leaving some buffer for unexpected expenses).

Income Tax Implications of the NSF GRFP

Your NSF GRFP stipend is subject to federal income tax. (It is usually subject to state and local income tax as well, but there are some exceptions.)

Further reading:

- Grad Student Tax Lie #1: You Don’t Have to Pay Income Tax

- Grad Student Tax Lie #4: You Don’t Owe Any Taxes Because You Didn’t Receive Any Official Tax Forms

- Grad Student Tax Lie #5: If Nothing Was Withheld, You Don’t Owe Any Tax

However, the taxation of fellowship stipends is handled completely differently by universities than assistantship pay.

Tax Reporting

While assistantship pay is reported on a W-2, fellowship stipends are not required to be reported in any particular way.

Receive Your Tax "Cheat Sheet"

Subscribe to the Personal Finance for PhDs mailing list for essential information to help funded US graduate students (citizens/residents) with their federal tax returns

A large fraction of universities, possibly the majority, do not report outside fellowship stipends on any official tax form. At most, the fellow might receive a courtesy letter, which is an informal letter stating the amount of the fellowship stipend received during the calendar year.

Some universities report fellowship stipends on Form 1098-T in Box 5 (along with other scholarship and grant income).

A small minority of universities report fellowship stipends on Form 1099-MISC in Box 3.

Whatever reporting mechanism used or not used, the important information to bring to your tax return preparation process is the amount of fellowship stipend paid to you during the calendar year. From that point, the fellowship stipend income is treated the same as any other fellowship/scholarship/grant income, and (possibly after some adjustments) it will ultimately be taxed as ordinary income.

Further reading:

Quarterly Estimated Tax

While you are required to pay federal and usually state income tax on your fellowship stipend, the vast majority of universities do not offer automatic income tax withholding on your fellowship stipend as they normally do for employee pay. (You should inquire whether automatic withholding is an option and use it if so, but the remainder of this section assumes it is not offered.)

This means that you will receive 100% of your gross fellowship stipend instead of your stipend net of income tax as you would assistantship pay. However, the IRS still expects to receive income tax payments throughout the year, so you will have to look into filing quarterly estimated tax.

Further reading: The Complete Guide to Quarterly Estimated Tax for Fellowship Recipients

As a default position, you should assume you are responsible for paying quarterly estimated tax. It’s possible that you won’t be required to in the year you switch on or off of the fellowship or if you’re married to someone with a high income and high withholding, but even in those cases it’s prudent to check.

The way you calculate your quarterly estimated tax due (and figure out if it’s required of you) is by filling out Form 1040-ES. That form will give you the amount of the payment you are supposed to make four times per year and an estimate of your total tax due for the year. You can make the payment online at IRS.gov/payments or through a host of other mechanisms.

Whether or not you are required to file quarterly estimated tax, it’s a great idea to set up a personal system that simulates automatic tax withholding. Open a separate savings account labeled “Income Tax” and transfer in the fraction of each paycheck you receive that you ultimately expect to pay in tax each time you are paid. Then, draw from that savings account when you make your quarterly or yearly tax payments.

Investing Implications of the NSF GRFP

The upside of receiving the NSF GRF is that your income is most likely higher than it would have been, which means you have an increased ability to achieve financial goals during graduate school such as debt repayment, saving, and/or investing.

Free Email Course: Investing for Early-Career PhDs

Sign up for the mailing list to receive the free 10,000-word email course designed for graduate students, postdocs, and PhDs in their first Real Jobs.

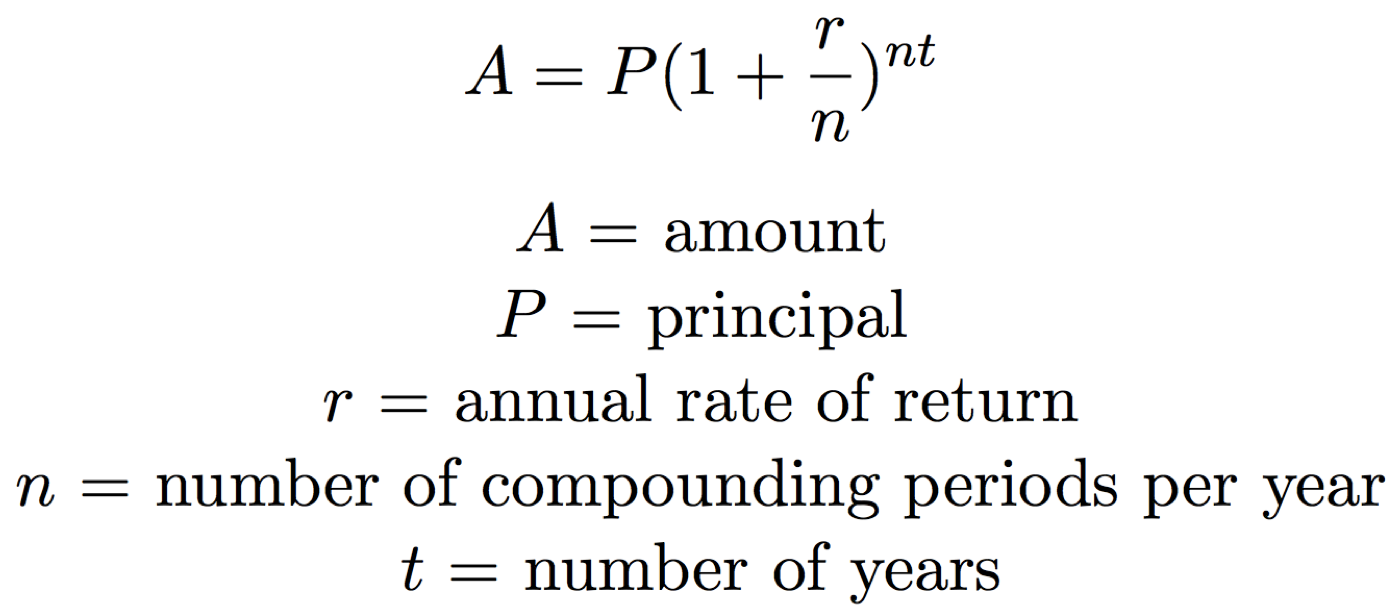

Through 2019, fellowship income, like that of the GRFP, was not eligible to be contributed to an Individual Retirement Arrangement (IRA). However, starting with tax year 2020, fellowship income is eligible to be contributed to an IRA, eliminating the only major downside of receiving fellowship income.

Further listening: Fellowship Income Is Now Eligible to Be Contributed to an IRA!

An IRA is a tax-advantaged retirement savings vehicle. It’s a great idea to use an IRA (or other tax-advantaged retirement vehicle such as a 401(k) or 403(b)) for your retirement savings as it helps you maximize your long-term rate of return by protecting your investments from taxes. As a graduate student, you almost certainly don’t have access to the university 403(b), so the IRA is basically the only game in town for tax-advantaged retirement savings.

Further reading:

- Everything You Need to Know About Roth IRAs in Graduate School

- Why the Roth IRA Is the Ideal Long-Term Savings Vehicle for a Grad Student

- Should a Graduate Student Save for Retirement in a Roth IRA?