In this episode, I break down my own budget from 2017. My husband and I earn about $100,000 per year and live in Seattle, WA with our two small children. I detail our top five expenses (rent, groceries, travel, kid spending, and transportation) as well as the financial goals that we’re currently working toward. I give some advice for a budget-conscious person moving to Seattle. Finally, I share what it’s like to be a renter in Seattle’s rapidly inflating housing market, spending nearly $20,000 per year on rent and feeling shut out of the housing market.

Links mentioned in episode

- Podcast Season 1 Episode 1

- Avoiding an Expensive 401(k) Plan through Self-Employment

- Frugal Blitz

- Frugal Month

- Volunteer as a guest in Season 2

1:05 Q1: Where do you live and what is your income?

My husband, Kyle, and I live in Seattle, WA, with our two daughters, a 2-year-old and a newborn. We moved here in 2015 for Kyle to take a job at a biotech start-up. I am self-employed; Personal Finance for PhDs is my main business, and I also have a side hustle. Our household income in 2017 was around $100,000.

Further reading:

- Why I Still Side Hustle Even Though I’m Self-Employed

- $100K Doesn’t Feel Like Enough in Seattle, Survey Shows

1:40 Budgeting Background Info

- Kyle and I practice percentage-based budgeting, which means that from our gross income we:

- Pay income and FICA tax

- through payroll deductions on Kyle’s income.

- through quarterly estimated tax on my self-employment income.

- Tithe (donate 10% to our church).

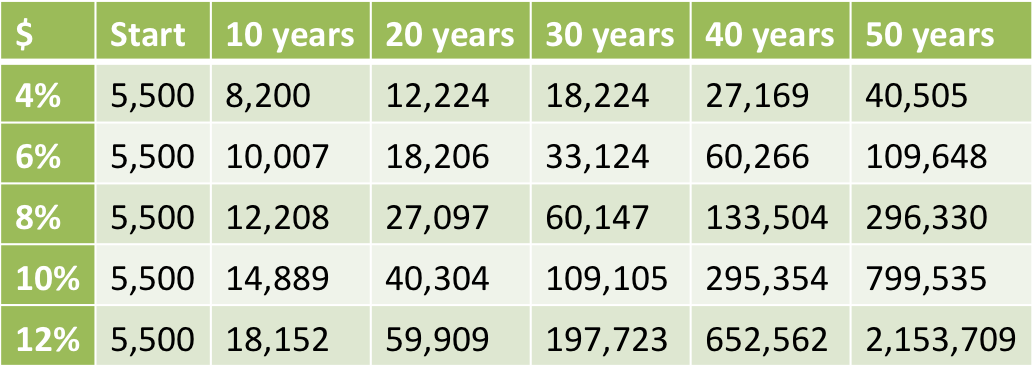

- Save into retirement accounts (20% in 2018, 18% in 2017).

- Pay income and FICA tax

- We live on one income. Kyle earns most of household income and has a regular salary, so we base our budget entirely off of his income after the percentage-based allocations. All of my income after the percentage-based allocations goes to savings. This helped a lot when my self-employment income was irregular, although now I pay myself a salary.

- We budget for our regular (monthly) and irregular (yearly) expenses. More details about this system can be found in Season 1 Episode 1.

Further reading: How to Pay Tax on Your PhD Side Hustle

Join the Mailing List to Download Frugal Tips for PhDs-in-Training

The download includes 30+ frugal tips for PhDs-in-Training with links to video and additional written content.

You'll receive 1-2 emails per week to help you make the most of your money during your PhD training.

4:19 Q2: What are your five largest expenses each month?

Our total spending in 2017 was approximately $47,500 (excluding the above percentage-based allocations and health insurance premium paid as a payroll deduction).

5:09 #1 Expense: Rent

In 2017, we spent $18,870 on rent, which is a monthly average $1,570 and 40% of our total spending.

Our rent went from $1495 per month to $1645 per month.

We live inside Seattle city limits. Our apartment in older building with no amenities. The apartment is approximately 850 square feet and has two bedrooms and one bathroom. We chose the apartment based almost solely on location and price.

When we next move, we definitely want to get a place with a dishwasher! Our kitchen is pretty small. We cook and eat in a lot and with two little kids so we wash a lot of dishes every day.

6:38 #2 Expense: Groceries and Household Consumables

In 2017, we spent $7,733.54 on groceries and household consumables, which is a monthly average of $644.46 and 16% of our total spending.

This amount of spending feels high to me, and this is a category that I keep a close eye on.

We meal plan, eat virtually every meal out of our own kitchen, and usually buy food on the less processed side of the spectrum. We shop mostly at Costco and Fred Meyer and also a little at QFC. We don’t seek out organic or similar food except when we buy directly from the from farmer’s market.

Most likely the reason we spend a lot in this category is simply that we eat a lot, and the food we eat is on the more expensive side of the spectrum. These days, we alternate between eating low carb/Whole30-ish and eating the standard American diet, which means we are consistently eating meat and often dairy, which are both more expensive categories.

Our typical meals are:

- Breakfast: Egg casserole with sausage, sweet potato, onion, and spinach.

- Lunch: Chicken yellow curry, chili, sausage and eggplant hash, fish plus sautéed spinach or zucchini.

- Dinner: Meat with vegetable, e.g., balsamic vinegar chicken and roasted asparagus. Kyle’s favorite meal: Brussels sprouts bowls. One of my favorite meals: Mexican breakfast bowls.

- Snack: PB and almonds

Our toddler is a very good eater. We followed the baby led weaning technique, and now she eats the food we do plus more milk, fruit, and cheese.

9:57 #3 Expense: Travel

In 2017, we spent $3,482.47 on travel, which is a monthly average of $290.21 and 7% of our total spending.

I was surprised that travel ended up in our top 5 because I perceive that we travel much less than before we had children.

In 2017 we traveled on five occasions: two weddings, our 10-year college reunion, a memorial service, and to one of our parents’ homes for Christmas.

In addition to the flights, on various of these trips we paid for hotels, rental cars, meals, entertainment, and registration.

We definitely spend more per trip than when we were in grad school. Flying with a baby has spurred us to take direct flights at convenient times of day instead of purchasing the lowest fare available.

Our current frugal practice regarding travel is to rewards credit cards; we currently have the Alaska Airlines credit card and the Chase Sapphire Reserve credit card.

12:10 #4 Expense: Miscellaneous Kid Spending

In 2017, we spent $2,688.66 on miscellaneous expenses for our oldest daughter, which is a monthly average of $224.06 and 6% of our total income.

This is the category I have the least handle on as it is so unpredictable.

Our one regular expense included in this category was preschool tuition, but that only applied for a few months

Our spending out of this category was all over the place

- Medical copays, occupational therapy copays, breastfeeding medicine.

- Travel car seat and travel stroller (in addition to the ones we use at home).

- Bookcase, mattresses for grandparents’ houses, jacket, and teether.

- Toddler class at the local community center and zoo membership

This is a fly-by-the-seat-of-your-pants category.

I was surprised these miscellaneous kid expenses as a category cracked top 5 because our first-time-parent start-up expenses hit in 2016.

14:30 #5: Transportation

In 2017, we spent $2385.77, which is a monthly average of $197.98 and 5% of our total spending.

I really thought transportation expenses wouldn’t be in our top five; low transportation spending is a point of pride for me!

It turns out that 30% of the spending was from our regular monthly budget, and 70% was from our irregular expenses budget. Our regular expenses included gas and parking, whereas our irregular expenses included car insurance, registration, and maintentance.

We own one older car and don’t use it for commuting. Kyle has a sub-10 minute bike commute and I work from home. We generally just use the car for errands, activities with the kids, church, grocery shopping, etc.

Those irregular expenses hit in only 3 months of the entire year, which is why I sort of forgot about them. We pay our car insurance once every 6 months, and it’s inexpensive. We spent over $1000 in car repairs/maintenance in 2017, which was unusually high and not a yearly occurrence.

All of our top 5 expense categories together accounted for 74% of total yearly spending.

17:20 Q3: What are you currently doing to further your financial goals?

1: Retirement Savings

We save a fixed 20% of our gross income into our retirement accounts.

We actually don’t use Kyle’s 401(k) through work at all because of high fees. Instead, we put our retirement savings into our two Roth IRAs and my individual 401(k), which we had total control over. Kyle’s 401(k) is the account of last resort because there is no match.

Details on Emily's Roth IRA

Sign up for the mailing list to receive a 700-word letter on which brokerage firm I use for my Roth IRA and what it's invested in.

2: Down Payment Savings

In 2017, we saved 21.7% of my income and all of our self-tax refund for a down payment on a home.

Further reading: Creating Our Self-Tax Refund

In early 2018, paused our down payment savings to save into a fund to help with expenses and lost income associated with the birth of our 2nd daughter’s.

Once those expenses have settled, we’ll resume saving for our down payment. In the remainder of 2018, we plan to save a fixed rate from Kyle’s income plus 22.7% of my income.

Our initial down payment goal was $60,000, but now that we’re getting close to that number, we want to keep saving and perhaps make $100,000 our next goal. We’re not necessarily shooting for a 20% down payment, but having a lot of money available for the down payment, other fees and expenses, and moving costs will be good.

3: Kids’ College

We save a nominal amount of money toward our children’s college expenses. We plan to hit this goal harder after we buy our first home.

4: Paying Down Student Loan Debt

We are currently making only the minimum payments on a standard 10-year repayment plan on my student loans. Episode 1 explains why we have not yet paid off these loans. However, as of the day of the recording, we received an update on the loans and decided to pay them off completely.

20:47 Q4: What don’t you spend money on that might surprise people?

1: Kid Expenses

A: Childcare

We don’t spend much money on childcare because of the way we have structured our life. Kyle has a regular job, and I’m self- employed. I’m also our children’s primary daytime caregiver. I work when Kyle is home with the kids and when they are sleeping. In 2017, I worked around 20 hours per week with this system. When I travel for speaking engagements, we hire sitters through a service we subscribe to, but this is irregular. We don’t have any regular childcare as of now. We are considering hiring a part-time nanny this fall since we now have two kids to help keep my work hours up.

B: Diapering and Clothing

We cloth diaper, which means we paid a bunch of money for diapers in 2016 but not in 2017. We use disposable diapers when we travel and disposable wipes sometimes.

Further reading: Cloth Diapering in an Apartment

We didn’t have to spend any money on clothes in 2017. The communities we’re plugged into gave us lots of gifts, hand-me-downs, and borrowed clothes.

Further reading: Outfitting Our Baby with Hand-Me-Down, Borrowed, and Used Stuff

When we buy stuff for our kids, we often look to the secondhand market first.

2: Eating Out

We only spent $254.38 on eating out in 2017, which is an average of $21.20 per month. This is a shockingly low figure to me. Since having our first child, we basically don’t go out to eat or get take-out any more!

We don’t drink coffee, which many people pay for out of the house.

Kyle does buy a beer at occasional happy hours with his coworkers, which probably accounts for a good fraction of the spending in this category. I’m in a non-drinking phase of life due to breastfeeding and pregnancy.

3: Entertainment

Our only recurring entertainment expense is Netflix. We are still avid Duke basketball fans, but as we’re not attending games anymore that is an inexpensive hobby.

This low spending is a big change from before we had kids. We used to have season tickets to the Broadway musicals series our local theater, which is not something we’re doing now.

Most of our entertainment now revolves around our toddler: going out doing activities or playing with friends and even at home. We attend lots of free activities around Seattle: parks, toddler rooms and gyms at community centers, and libraries. We also hang out with her toddler friends and our kids tag along to game nights with our friends.

I’m chalking this low spending up to this being a unique phase of life! We expect to spend more in this category again later.

26:31 Q5: What are you happy with in your spending and what would you like to change?

Overall I am quite happy with our spending and progress toward our financial goals.

I don’t love that we spend almost $20,000 per year on rent, but it is reasonable for this city.

I’m not so happy with the grocery and kid expenses.

I feel like we’re spending a lot on groceries. I have some frugal practices, but could do more. During the Frugal Blitz this coming September, I will focus on frugalizing my groceries.

I don’t mind spending what we do on the children, I just want it to be more predictable! Perhaps we will institute a monthly cap on spending or try to anticipate the larger expenses as they grow.

28:11 Q6: What is your best advice for someone new to your city who is budget-conscious?

Focus on housing and transportation: Do your research in advance about where to live and what your commute will be like.

Renting and buying in Seattle is on a quick timeline. Places listed for rent are available immediately or like one week out, and little notice is required when you move out of a place. In 2015 when we moved to Seattle, the rental market was quite competitive. We had to make quick decisions on where to apply and compete with others.

We handled this market by researching the prices in the neighborhoods of interest before we started our moving trip, even though we were not expecting that any of those same rentals would be available when we arrived. This gave us the ability to spot a good deal.

Further reading: Apartment Search in Seattle

You should factor in your commute if you know where you’ll be working. A lot of people avoid the higher housing prices by living outside of Seattle, but that usually increases their commute time. We chose to eliminate the commute and pay the higher housing cost so that we could have more time together.

Don’t assume you’ll commute by car. Over 50% of people in Seattle commute by other methods: bus, biking, walking.

30:52: Q7: Would you like to make any other comments on what it takes to get by where you live on what you earn?

In Seattle, the high tech industry is quite dominant. Those positions are very well paid, and housing costs are being driven up quickly.

In 2017 and the first half of 2018, Seattle had the fastest-appreciating housing market.

Housing prices are heading up quickly, and it’s very discouraging for renters/first-time buyers.

Purchasing a home in our current neighborhood (maintaining that short commute) would be very difficult for us. Even earning $100,000 per year, the most we could afford in our neighborhood is the lowest priced condo possible. The median home value in our neighborhood is almost $1,000,000. The median condo price in Seattle is nearly $550,000. It’s also very hard to not get swept up in the hype of the market.

We are leaning against ever buying in Seattle. Housing is quite a struggle for first-time home buyers.

I’d love to hear from other PhDs (in training) who make less than what we do on how you manage your expenses!

Join the Mailing List to Download Frugal Tips for PhDs-in-Training

The download includes 30+ frugal tips for PhDs-in-Training with links to video and additional written content.

You'll receive 1-2 emails per week to help you make the most of your money during your PhD training.