Did you start receiving a fellowship this academic year as a graduate student or postdoc? First, congratulations! Second, I must clear up a pernicious misconception about fellowships in the US: you do owe federal income tax (and probably state, too) on your fellowship income. If income tax is not being withheld from your stipend/salary (and the majority of universities do not offer withholding on this type of income), you may be responsible for making quarterly estimated tax payments throughout the year. The next payment is due tomorrow, January 16, 2018! This post will guide you through how to determine whether you owe quarterly estimated tax and how to pay it if so.

Do You Receive Your Gross Income?

The IRS expects to receive income tax payments throughout the year, not just each April. Employees almost always have income tax withheld from their paychecks; instead of receiving their gross (full) income, their employer sends approximately the amount of tax the employee owes from each paycheck to the IRS and the employee receives the rest (net income).

Fellowship recipients (when the term is used conventionally; perhaps not universally) have non-compensatory pay and are not considered employees of their universities. Most universities do not offer income tax withholding on fellowship stipends/salaries. Taxpayers who do not have income tax withheld from their salaries (or who have too little withheld compared to the amount of tax they owe) are sometimes responsible for manually sending money to the IRS. This is called making quarterly estimated tax payments.

If you are a fellowship recipient (e.g., the NSF GRFP), your first step is to confirm that you are in fact not an employee, and your second step is to check whether you are receiving your gross or net income.

Step 1: The easiest way to determine if you are an employee (or rather, confirm that you are not) is to check whether you receive a W-2 for your fellowship income. (If you had an assistantship in this calendar year, you will receive a W-2 for that position, so be sure to check specifically about your fellowship income.) However, if you just started your fellowship in the 2017-2018 academic year, you aren’t due to receive (or not receive) your tax forms until the end of January 2018, and the estimated tax payment is due in mid-January. Your next best option is to inquire into what tax form you will receive for your fellowship stipend/salary. Non-compensatory pay will appear on a 1098-T, 1099-MISC, or courtesy letter or will not be reported in any way. Compensatory pay (indicating that you are an employee) will appear on a W-2. You should try asking your departmental administrative assistant, university fellowship coordinator, Bursar’s Cashier’s office, and/or payroll office. You will most likely be told that they “cannot give tax advice,” but confirming what type of tax form your income generates is not advice.

Step 2: Having confirmed that you are not an employee (if you are, you don’t need this post!), double-check the stipend/salary amount that hits your bank account. If you multiply it by the number of pay periods over which you will receive it, is it equal to the gross fellowship stipend/salary you were told you would receive or is it less? If it is less, did you at any point file a W-4 (e.g., when you had an assistantship)? You may be one of the few students/postdocs who has income tax withheld from a fellowship stipend/salary. As stated earlier, a small minority of universities do offer withholding on fellowship income, and they should use a W-4 to determine the amount of withholding.

If you are not an employee and are not having income tax withheld from your fellowship stipend/salary, you may need to make quarterly estimated tax payments.

Are You Responsible for Paying Quarterly Estimated Tax?

The IRS explains who is responsible for filing quarterly estimated tax on Form 1040-ES p. 1.

Right off the bat, you are not required to pay quarterly estimated tax if in the previous tax year your total income was zero or you did not have to file a tax return (and your return covered all 12 months). For example, if you were a student for all of 2016 and either didn’t have an income or your income was so low that you didn’t have to file a tax return, you aren’t required to make quarterly estimated tax payments.

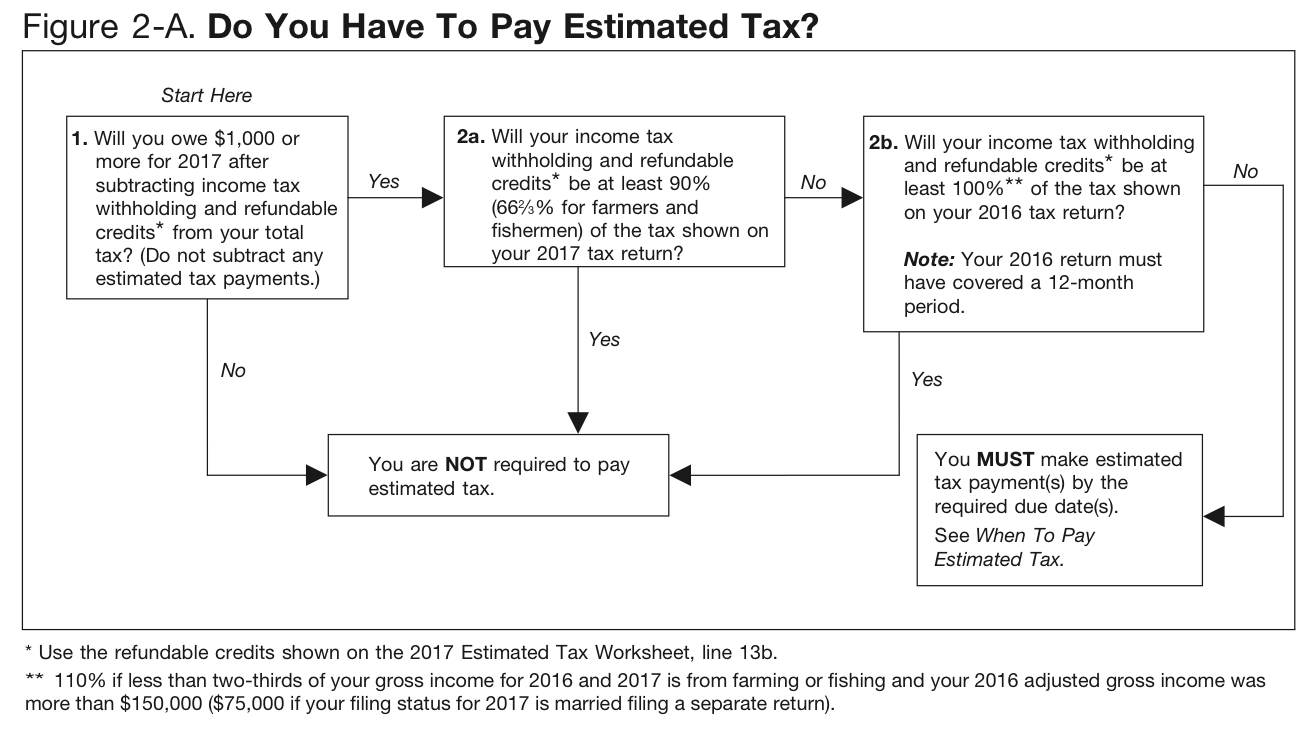

If that first provision doesn’t apply to you, the IRS has a helpful flow chart on Publication 505 p. 24.

At this point, you’re going to have to do a few calculations to determine what amount of additional tax you owe for the year (additional to any withholding you already had). You simply need to fill out the worksheet on Form 1040-ES p. 8 for your household. It looks sort of involved but if you have a simple financial life you won’t actually need to put very many entries into the worksheet. You will need at your fingertips your 2016 tax return (or at least the total amount of tax you paid), your gross income for 2017, the amount of income tax you had withheld in 2017 (if any) and an educated guess as to your 2017 deductions and credits (your 2016 return will be helpful for this).

Once you calculate the amount of tax you owe in total for 2017 (Form 1040-ES line 13c), you can determine whether you are responsible for paying quarterly estimated tax.

First, look up the total amount of tax you paid in 2016. Second, take your total tax due for 2017 and multiply it by 90%. The smaller of these two numbers is the amount of tax you need to pay throughout 2017 to avoid a penalty (Form 1040-ES Line 14c).

Subtract the amount of income tax you had withheld in 2017 (Form 1040-ES Line 15) from the amount you need to pay to avoid a penalty. If the result (Form 1040-ES Line 16) is less than $1,000, you are not required to make a quarterly estimated tax payment. If the result is greater than $1,000, you are required to make a payment.

Please note that just because you are not required to make quarterly estimated tax payments does not mean you will avoid paying tax the whole year, only that the additional tax due does not have to be paid until you file your 2017 tax return this spring. Now that Form 1040-ES has given you some warning, use the next few months to prepare to make that lump sum income tax payment.

How to Pay Quarterly Estimated Tax

If you are required to make a quarterly estimated tax payment, the calculation is pretty simple since this is the last payment due for 2017! You should make a payment for all the additional tax due that you calculated you owe (Form 1040-ES Line 16a). If your calculations were exact, when you file your 2017 tax return in the spring, you won’t receive a refund or owe any additional tax. More likely, filling out your full tax return will bring to light a few adjustments in your calculations, so you may end up receiving a small refund or paying a small amount of additional tax.

The easiest way to make your quarterly estimated tax payment is online at www.IRS.gov/payments (find all your payment options on Form 1040-ES p. 3-4 or Publication 505 p. 32-33).

If you were unaware that you had any income tax liability on your fellowship income and are unprepared to pay what you owe by January 16, 2018, don’t avoid the issue! Give the IRS a call and they may be able to work with you to minimize the penalties you owe (though not the interest).

Calculating your quarterly estimated tax is not very difficult; the most challenging aspect is knowing that you’re supposed to do it! If you are a new fellow and this is your first time making a quarterly estimated tax payment, rest assured that it will be easier going forward. You first quarterly estimated tax payment for 2018 is due on April 17, 2018. You’ll want to freshly fill out the 2018 1040-ES once it’s available, but it should be similar to the form you just worked through.