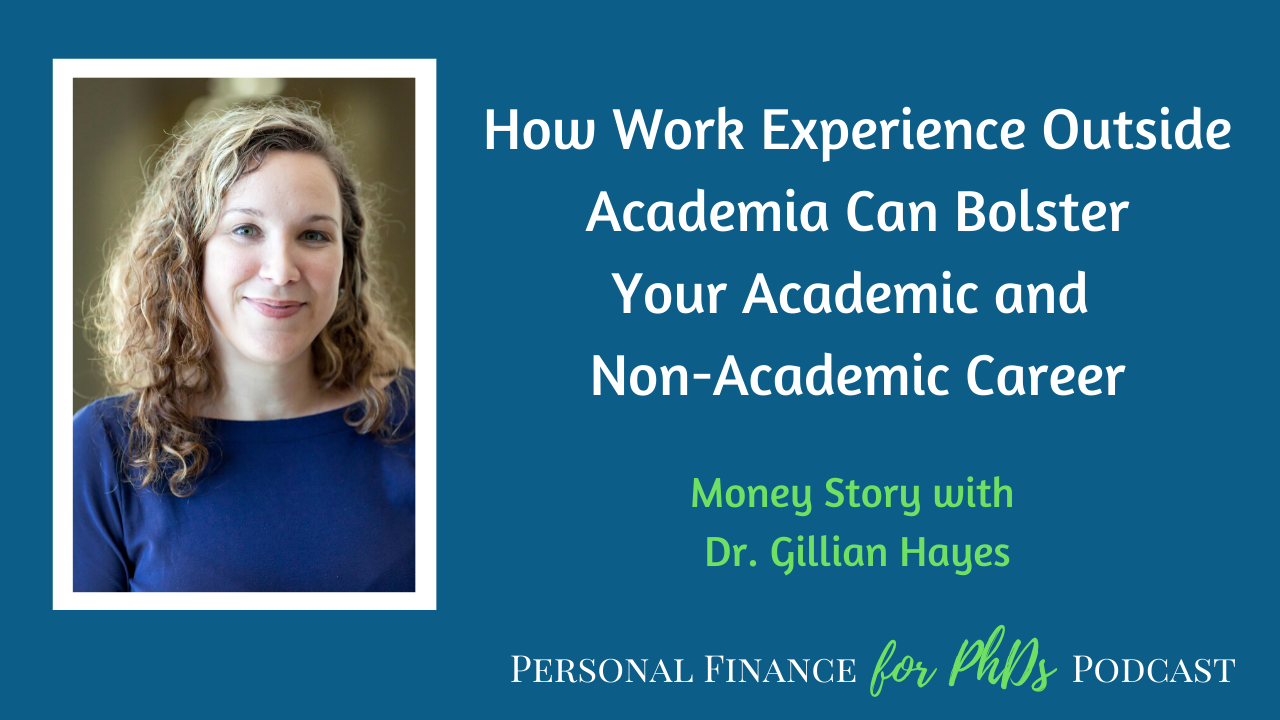

In this episode, Emily interviews Dr. Gillian Hayes, the Vice Provost for Graduate Studies and Dean of the Graduate Division at UC Irvine. Throughout her career as a computer scientist, Gillian has moved back and forth between roles in academia and industry; she argues that the division between the two is more porous than is commonly perceived inside academia and should become even more so for PhDs. Gillian consulted and completed internships as a PhD student and engaged in an even broader range of side hustles as a faculty member. We discuss the real and perceived barriers to side work that PhD trainees encounter in other disciplines. We conclude with why PhD trainees should consider non-academic careers and how to prepare for them.

Links Mentioned

- Find Dr. Gillian Hayes on Twitter

- Related episode: How to Find and Apply for Fellowships (with ProFellow founder Dr. Vicki Johnson)

- Personal Finance for PhDs: Financial Coaching

- Personal Finance for PhDs: Podcast Hub

- Personal Finance for PhDs: Subscribe to the mailing list

Teaser

00:00 Gillian: They’re not linear. People take all kinds of curving paths and I would very much like to see the university and academia in general, be a sort of lifelong learning and scholarship partner to people, for moments when they’re both in and out of where we are. Academia will always be here. Go do interesting things, come back. Let’s reconnect. And let’s find ways that we can make those boundaries a little bit more porous.

Introduction

00:32 Emily: Welcome to the Personal Finance for PhDs podcast, a higher education in personal finance. I’m your host, Dr. Emily Roberts. This is season six, episode six and today my guest is Dr. Gillian Hayes, the Vice Provost for Graduate Studies and Dean of the Graduate Division at UC Irvine. Throughout her career as a computer scientist, Gillian has moved back and forth between roles in academia and industry. She argues that the division between the two is more porous than is commonly perceived inside academia and should become even more so for PhDs. Gillian consulted and completed internships as a PhD student and engaged in an even broader range of side work as a faculty member, and we discussed the real and perceived barriers to side work that PhD trainees encounter in other disciplines. Don’t miss a minute of this fascinating conversation recorded in February, 2020. Without further ado. Here’s my interview with Dr. Gillian Hayes.

Will You Please Introduce Yourself Further?

01:31 Emily: I have joining me on the podcast today, Dr. Gillian Hayes, who is a Vice Provost and Dean at the University of California at Irvine. We’re going to be discussing side hustling and career development, both what Gillian has done in her own professional development and how she works with students on the same subject. It’s really pleasure to have you on today, Gillian. Will you please introduce yourself a little bit further to our audience?

01:55 Gillian: Sure. Thanks so much, Emily. I’m so glad to be able to be with you all today. I think you’re doing a wonderful service for our students. Just some quick background on me. My training is actually as a computer scientist. Both my undergraduate and PhD work was in computer science. I have a lot of background in working in industry and other places that I’m sure we’re going to talk about later. And the bulk of my research is actually focused on how do we help people who may not be included in the tech world, normally — so kids, underrepresented groups, elderly individuals — how do we help them get involved in the design process and really make responsible, ethical technologies. Here at UCI, since September, I have taken on the role of Vice Provost of Grad Education and Dean of the Graduate Division, which is a very long, convoluted way of saying that I get to be in charge of all the grad students here on campus and help them be as successful as they can be.

02:54 Emily: Yeah. So one big component of that is not only academic success, but success in their future careers. Obviously it reflects very well on your university and program if people go on to have careers success.

Career Path: Grad School to Faculty

03:06 Emily: Let’s start talking a little bit more about your own personal journey. Can you talk us through the work experience that you had prior to graduate school, if any, and then the side hustling that you did during graduate school?

03:18 Gillian: Yeah, absolutely. I should confess, I’m the child of two academics. Both have doctorates, were professors, so I understood academia in a way that I think, it’s important to contextualize the kind of privilege that comes with that. I think I always knew I wanted to go do a doctorate at some point, but beyond that, I was deeply confused when I finished undergraduate and I didn’t know what to do. And I did like all people who don’t know what to do and I went and worked for Deloitte, and sort of got the basic training of how do you be a consultant? How do you be a professional out in the world? I then worked for another company called Avanade, which was a spin-off of Accenture and Microsoft at the time, and just spent a lot of time learning the basics of being a professional before I went back to grad school. Then, while I was in grad school, I also continued to work. I’ve sort of, throughout my career, had this one foot in academia, one foot in industry kind of life. I worked for both Intel and IBM in internships. I also had a side gig driving the golf cart that serves people beer at a wonderful golf course in Georgia called Chateau Alon, which is probably my favorite job that I had in grad school. And then did some additional consulting for a company called Roundarch. So that was sort of all what I was doing while I was in grad school and before grad school, and I think they were all great experiences and can’t recommend it all enough.

Side Hustling During Grad School

04:44 Emily: Yeah. Let’s take a pause there because I think you were in not only a unique position because of your familial upbringing, but also because of your field, computer science, which is so highly employable with just a bachelor’s. Maybe the most of any academic field of any of my guests. So you got some great jobs right after undergrad, and then also continued to side hustle in graduate school. Now I’ve noticed — this is anecdotal, you can tell me if this has been in your observation as well — that computer science is the field that is maybe tied with engineering, but most likely to allow internships and encourage internships and other kinds of consulting and side work during graduate school. So there’s a very big, in my opinion, cultural difference between computer science and perhaps engineering, and then like the biological sciences, the humanities. Can you elaborate on that a little bit?

05:37 Gillian: Yeah. I think that’s a great observation, Emily, and it’s actually something I didn’t even realize was unique until I became a professor because I just thought, well, of course that’s what you would do. You go off to industry. It’s very much encouraged. It’s very much a part of the culture. There are industrial research labs, which I think is a piece that helps alot. So when you talk about interning as a PhD student in computer science or information science or other related fields, you’re typically going to a company that’s going to allow you, and in fact, encourage you to publish the work that you do while you’re there. And so not only are you making lots of money, typically more money in the summer, then you’ll make throughout the entire rest of the year, working at the university, but you’re also doing it in a way that advances your career and helps you publish and helps you build a network with researchers outside of the Academy. And I do think that you’re right, that’s quite unique, although growing a little bit more in other fields, but certainly not to the extent that you see in computing.

06:35 Emily: Yeah. And I don’t mean at all to set this up, like this can only happen inside computer science and never happens elsewhere. I just think that, yeah, in other disciplines, we need to take a page out of what’s going on inside computer science and engineering. And maybe it’s not formal internships, like maybe the structure isn’t quite there yet inside academia to allow for that. Like you said, maybe there aren’t publishing opportunities outside of academia in other fields, the way there possibly is in computer science, but I just think that people in other disciplines, it helps to open your mind a little bit to what’s possible in terms of internships or, you also mentioned consulting, like, can you elaborate a little bit more about that? These kinds of things that are potentially possible, even for people in other fields, if they seek out the opportunities. It might not be presented to them in the way that it is inside computer science, but doesn’t mean it’s not there.

07:21 Gillian: Yeah, I think that’s a great point. What I typically hear from faculty who are worried about their students interning, and this is true by the way, within computer science as well. There are some faculty who don’t like their students to intern, although it’s much more rare than other disciplines. But what I typically hear is, “well, how are they going to get their work done? How are they going to finish their dissertation?” All of those kinds of things. What I have seen in my career, and I’m actually trying to collect the data right now to do a study on this at UCI, to see if we can see if my anecdotal experience holds out across more people, is that actually, not interning or interning it doesn’t slow you down or speed you at particularly much. I did three internships at anywhere from three to five months while I was in graduate school and still finished in five years and did not have a master’s going in. And that’s not to say that I’m somehow special or so fast and so wonderful. But actually what I think is happening is you give your brain a little break from the dissertation and it’s amazing how much more quickly you can actually work on it.

08:25 Gillian: When I see students, and I do have them here, who they can’t intern, they can’t go away for whatever reason, perhaps they have family obligations or other things, and they’re not going to just move to the Bay area for the summer, things like that. Those students they’re not any faster. They really aren’t. And what I see them doing is churning a little bit, and really thinking through their dissertation almost too much. So I would encourage people in any field to seek out those consulting opportunities, even if it’s just do something for a few hours a week, write copy for somebody. Do some beautiful graphic design, if you’re an artist. Do some statistics. I mean, the amazing thing is how much people out in industry need consultants to just do basic statistical analyses, which most of our students in both the behavioral and physical sciences are very skilled in doing. Give your brain that break away from the dissertation and I actually think it speeds you up.

09:25 Emily: Yeah, I actually really agree. I did not intern or anything where the long monotony of the six years I spent in graduate school was not broken up by periods of fresh, different work in any way. That is one of my semi regrets of that time. I want to throw another like possibility in here, not just internships, not just consulting, but something that may be a little bit more palatable to academics, which is a fellowship. Doing a professional fellowship is also sometimes possible and may be something that your advisor is more likely to look favorably upon than some of these other kinds of work. For example, after I finished graduate school, I did a three month science policy fellowship at the National Academies in DC. That fellowship is available to current graduate students, as well as recently graduated PhDs. That’s just another kind of thing you can consider. I had a previous interview, which I’ll link in the show notes with Vicky Johnson from Pro fellow. She runs a database where you can look for these kinds of opportunities for professional fellowships, as well as fellowships that might fund you. Go check that out if you’re looking for something, something else to do that’s going to give you this wider network, this different kinds of experience to stimulate your brain in a different way than just the research you’ve been doing.

10:37 Emily: Okay, so very exciting what you were able to do, what other students could potentially be able to do. Can you say a few more words about how these opportunities for side hustling and interning that you took in graduate school, built your career and set you up for your post PhD job or jobs?

10:54 Gillian: Absolutely. They’re really essential and are a big part of my career story. One of my mentors at Intel actually wound up being on my thesis committee in the end and has continued to be a really wonderful mentor to me throughout my time. Lots of other interns — one of the things that’s great about interning is you meet a bunch of other people who are PhD students at other universities, or sometimes undergraduate or master’s students as well, and they become a part of your professional network. Often companies really roll out the red carpet for interns over the summer. And so you’re going to these fun events and you really get to know a lot of other people. That becomes a really essential part of who you are 20 years later, and I look back now and people that I met as part of an internship that aren’t in my field, that I never would have met otherwise, are some of my good friends now and they’re also professional colleagues.

11:51 Gillian: The other thing I would say though, is it’s not just the industry or the research internships or the fellowships or the kinds of things we’ve been talking about. I sort of joked earlier that my favorite job in grad school was driving the beer cart at the golf course. And I think sometimes we can tend to look down on those kinds of jobs or feel like, well, the only reason you’re doing that is to make a little extra money because we don’t pay grad students enough. Sure. Those things are probably all true, but it’s also the case that I drove around in the most beautiful setting you can imagine and brought all of my books and journal articles with me and parked on the side and read. And again, just got a head break. Just got out of my home, got out of my lab, all of those places. Meet interesting people. You never know who you might get to know and think about in these places. So whatever this sort of side hustle is, I think it’s really good for your brain and for your mental health and for your network.

Side Hustling Post-Grad School

12:49 Emily: So in the jobs that you’ve had after your PhD, have you continued to work on the side and still develop and maintain those networks? Or have you been an academic and solely focused on that?

12:02 Gillian: I am apparently not able to focus on one thing at a time ever. I think that’s okay in academia, actually. It’s part of what makes life so interesting. But no, I’ve absolutely continued to do variety of side hustles. So one of the things is, I took a break. As soon as I got my shiny, new assistant professor job, I went and went back to Roundarch and worked as a consultant again, and just really got to…I always talk about it as cleaning my brain. I was in the slog of writing this dissertation and it’s so painful. You finally get it over the line, and back then we had to measure the margins and do all of this painful stuff, and turned it in and went and got to fly around and talk to people about building websites for a while. That felt really good.

13:53 Gillian: Then I remembered why I left consulting in the first place, because I got kind of bored with it, and got to start my assistant professor position. That cycle has been really important throughout my career. I’ve continued to do consulting on the side, in terms of both technology-related consulting and user experience, and so on. But also because of my research in the autism space, I’ve been able to consult with a lot of folks in K-12 and in special education and help shape where the state of California is going in terms of our care and support of people with autism and related conditions. That’s been valuable both in terms of feeding my research and really understanding what’s out there practically, but also in terms of feeding my own ability to exercise different parts of my brain.

14:40 Gillian: I would also say, academics, they won’t always refer to it as a side hustle — we like to be very pure — but writing books is basically the ultimate side hustle, as far as I’m concerned. We get judged on it because it’s part of the tenure and promotion process. But if you write the right book, that generates all kinds of interesting things — speaking opportunities, consulting opportunities, other things that I think can continue to be important no matter what field that you’re in.

15:11 Gillian: I took it a little further than most in terms of side hustling, which is I started out doing a little bit of consulting for a couple of founders that I knew well from a startup and wound up running the entire company. That’s probably more than most people will do, but I did spend a couple of years as a CEO. What I’ll say there is sometimes your side hustle becomes your main gig for a little while. I took some leave from the university so that I could do that. And I would say to people, if that happens, go for it. You can take a leave of absence. So often people think, “Oh, I can’t get off the grad student treadmill” or “I can’t get off the tenure treadmill” or whatever. You can take a leave of absence for a couple of years and academia will always be here. It’s obviously not for everyone, but I really value the time that I had being able to run a small company and watching them now at a distance under someone else’s leadership and continuing to excel is so pleasurable for me.

16:10 Emily: I’m really glad that you brought up there can be these blurred lines between what is your job as an academic and what is stuff you do on the side, because all of it can be related to your area of expertise and just expressed in different ways.

Commercial

16:28 Emily: Hey, social distancers, Emily here. I hope you’re doing okay. It took a few weeks, but I think I have my bearings about me in my new normal. There is a lot of uncertainty and fear right now about our public and personal health and our economy. I would like to help you feel more secure in your personal finances and plan and prepare for whatever financial future may come. You can schedule a free 15 minute call with me at PFforPhDs.com/coaching to determine if financial coaching with me is right for you at this time, I hope you will reach out, if only to speak with someone new for a few minutes. Take care. Now back to our interview.

How Side Hustles Are Viewed in Academia

17:14 Emily: Can you talk to me about structurally, how this has worked for you? You just mentioned you’ve taken official sounds like full time leaves of absence from your job, but do you have, for instance, like an 80% position or have you at some points to allow time for these side things or have you always been kind of a hundred percent at the job and just pursued these outside of…I don’t know, how does this work, time management wise and also official position wise?

17:42 Gillian: Yeah. So official position wise, it really depends as a grad student, it’s fairly easy to sort of zoom in and of things. I did, what’s called an off cycle internship one year and was away for fall semester. Just a matter of filing some paperwork with the university to allow me to do that. That allowed me to be at my internship for five months instead of just sort of the normal three of the summer, which was really, really valuable. It also allowed me a lot of access to people who get a little maxed out in the summertime because there’s so many interns around. I would definitely recommend thinking about being creative with those kinds of things.

18:19 Gillian: Many universities, even if you’re a full time, faculty member have consulting allowances. You can maybe consult X number of hours per year and the university’s not bothered by it. If you do more than that, then they’ll typically want you to take some sort of reduced time or leave of absence, things like that. I would encourage people to really find out what the rules are at their different universities. It may be highly variable. Then the final thing is, my mother always says to me, if you don’t ask, you know, what the answer is. I really tried to take that to heart, and when I was starting working at AVIAA, I was aware that I was also running a master’s program that I was quite attached to, and I didn’t want to let that go. I sort of sat down and tried to think about, okay, if I keep running the master’s program, teach this little bit that will go with that, and I keep supervising the PhD students I have, because you don’t let your PhD students drift, even if you go off to do something else, what does that kind of look like time-wise? I went to my Dean and my department chair and said, I’d like to take a reduced workload. So basically these are the things I’m going to do and not going to do anything else. What does that look like percentage wise? And I’ve talked to a lot of different people who’ve done this. Anywhere from they’re employed at the university 5% time to maybe they’re employed 50%, 80%. You sort of get to different levels and whatever you think is appropriate. My Dean and my Chair looked at that and said, “yeah, that seems about right, we’re good with that,” so I was able to take reduce time, but not a full leave away.

20:02 Gillian: I would just say to people, you never know if you don’t explore it. So think about it and investigate it because you may well be able to do these things, partially. I also was always very upfront with our board of directors and with the founders of the company that I was still going to be doing XYZ things affiliated with the university. And they were good with that. From all of their perspectives, the idea that I would maintain a connection with this wonderful place of scholarship that would potentially bring us excellent new hires and other kinds of people was great. On the surface of it, and before I made those requests, lots of people said to me, “Oh, you can’t do this or you can’t do that,” but I thought, well, maybe. Let’s just ask and find out. So I would encourage people to ask.

20:47 Emily: Yeah, I’m so glad you brought this up and I want to take kind of a grad student or postdoc, spin on that question. Because what I hear a lot from especially graduate students is “I’m not allowed to have a side job or a side income,” and either that’s because of the terms of the assistantship that they have, or the terms of the fellowship that they’ve accepted, or it’s just something cultural that they’ve absorbed, or maybe their advisor said something more explicitly, but I think there’s a range of like, what’s actually permitted, either legally or contractually. And of course, for international students, that’s a whole other discussion of what the visa allows, which is nothing except for like official OPT kind of stuff. But for citizens or residents in the US, can you just talk around this a little bit of is it worth asking, even if you think the answer is going to be no, look at your contract, or what?

21:44 Gillian: I think it’s always worth asking. And I’ll answer that in a couple of ways. One of them is, and I saw some really interesting research, I’ll try to dig it up and send you the link if I can find it. But essentially, if you ask grad students, what do they think their advisor wants of them? They’ll essentially say to get an R1 tenure track position, to have this like life of the mind, to be a mini version of their adviser. And then if you ask the advisors, what do they want of their students, broadly, in a very generic, hypothetical, meta kind of way, they’ll say the same. But if you ask the faculty, think about your last X number of students — I forget what it is, two, three, four, whatever — who’ve graduated with you. What do you think you want for them? Suddenly you start to see industry jobs, government jobs, community colleges, other kinds of two and four year opportunities. Not these sort of tenure track PhD granting institution kinds of jobs. And it’s because we’re sort of inculturated in a broad way to think, yes, we want to create more little faculty that look just like us. But if you think about specific students, you often recognize, well, actually their passion and their strengths lie elsewhere.

23:02 Gillian: It’s that disconnect that I think many of the students are feeling. They know that their advisor, in a broad sense wants this thing, but maybe it’s not for them. If they really open up that conversation, I think most faculty really do want to support them and be open to that. I think it’s always worth asking. Also, the truth is, if you’ve got one of those few faculty that just aren’t interested and aren’t going to want to support you, no matter what, for me, I would want to know that because maybe I need to find a different person to work with, or maybe they stay my primary supervisor, but I find some additional mentorship on the side that can help me get to the places I need to go and that I want to go. I think it’s always worth asking.

23:46 Gillian: The other thing I would say is you can interpret contracts in all kinds of ways, and I’m not an employment lawyer, but what I can say is even if officially our ruling, as the University of California, is that people don’t have jobs outside, we don’t own your life. If I worked at Google or I worked at Deloitte again, or I worked wherever, they don’t get to tell me that I can’t go out on a Saturday morning and be a barista, if I want to. It’s the same here. We don’t own your personal time and your free time. So if it’s not disrupting your job here as a grad student researcher or your job here as a TA, I don’t see that we have a whole lot of standing to tell you that you can’t do it.

24:30 Emily: I’m really glad to have your perspective on, because I think this is something that students…I’ll call it a limiting belief. Like it’s a limiting belief that students have. I can’t, I’m not allowed to have a side job, have a side income. And I, like you, think it’s more important to examine this spirit of that rule or that cultural norm, because really the point is you want to be making progress on your dissertation. You want to put really good energy towards that on a consistent basis. And yeah, your advisor, or you, probably don’t want to be leaving at 5:00 PM every day to go to your second job as a whatever. But there’s so many jobs that you can have now in the internet age that you can do on your own schedule. That’s flexible. It’s not going to interfere with your work. As we talked about earlier, that will give you different kinds of energy and different kinds of stimulation that you aren’t getting through your primary position. I do like to think about the spirit of this. Like, is it interfering with your work? Does are advisor even really need to know about it, if they would never find out naturally. Now for these professional development opportunities, and especially something like interning, obviously you need to involve your advisor, potentially some other people in that conversation, but for a side gig, that’s a few hours a week, maybe they don’t need to know, if it doesn’t interfere.

25:44 Gillian: And you know, you never know. It’s not just that they don’t necessarily interfere, but they can also be argumentative in ways that you could never expect. Actually here’s a great example. I went to grad school with a woman who was a quilter on the side, made absolutely beautiful quilts. And I think sometimes she sold them, but just gorgeous. It takes a lot of time to be a quilter, but it didn’t interfere with her work. In the end, she actually developed this really incredible piece of software that helps teach children geometry, using quilting as a metaphor because of this thing she was doing on the side. Now, if someone had told her stop quilting, it takes up too much time, then she never would have done what she did for her dissertation.

26:29 Emily: Yeah, it is so, so beneficial to have these other areas of your life to give you not only balance, but to help you think about your work in different ways, and just to be like a whole person. You can still be a whole person during your PhD training, while on the tenure track, it’s all encouraged.

Non-Academic Careers

26:44 Emily: So let’s pivot a little bit to talking about non-academic careers. You’ve obviously had an academic career, as well as nonacademic aspects of your career. How can students who, as we were talking about earlier are statistically unlikely to end up in a tenure track position, even if they want to keep their hat in the ring for that sort of thing, how can they simultaneously prepare for a career outside of academia?

27:10 Gillian: Yeah, that’s a great question. The first thing I’ll say is, I think we need an educated workforce and an educated society, and the idea of having loads and loads of people with PhDs that work in places that are not universities is really appealing to me. I think it’s good for the world. I just want to sort of admit to my positionality there. But what I’ll tell you is I know a lot of CEOs of both big and small companies. I know a lot of executive leaders and they come to me and they ask me, where can they find people who can quickly digest an enormous amount of information, write up interesting, analytical thoughts about that. Talk about it with other people, teach it to them, explain it to them and figure out what we do next. And I’m like, that’s someone with a PhD. They’re looking all over business for people with those skills. It’s exactly what we teach, no matter what your field. It’s absolutely the case that the market needs it.

28:10 Gillian: Now we have some work to do to translate and help people understand and help people be marketable and all of those things, but that kind of work and the kind of critical thinking skills that people develop doing a doctorate is absolutely what the highest levels of leadership in the corporate world need desperately. Obviously also in government and nonprofits and other places like that. What I would say to people is just be thinking all the time about how do I translate what I do into something that other people can understand. And I spend a lot of time with people who want to translate an academic CV into a more typical resume, just helping doing that translation work. I would encourage people to seek out people like myself, who’ve had these different kinds of careers. I’m happy for podcast listeners, you can feel free to reach out to me. I might not respond right away, but I’m happy to look at things, and just figure out how do you explain yourself out into the world? That’s the first thing I would say.

29:12 Emily: I actually want to jump in there and plug a colleague of mine, Beyond the Professoriate, Jen Polk and Maren Wood’s business. This is the kind of space that you can join and learn these types of skills, see examples of how other people have made exits from academia into other interesting careers, and have community with other people who are going through the same process. Beyond Prof is one of the places where you can do that.

29:37 Gillian: Absolutely. I direct people to Beyond Prof all the time. That’s actually a better resource than me. They will respond to you more quickly. Definitely check those out. The other thing I would say is, and I’m going to pick on you a tiny bit, Emily, is even using that phrasing of exiting the university, right? One of the things that I sort of bounce up and down on a lot around here is the language of alt-ac, and post-ac, and academic exits, and these kinds of things. I don’t want to take away from people’s feelings. If that’s a helpful way for people to express what they’re going through, then by all means, go ahead, but we don’t have that same language for undergraduates who finish an undergraduate degree. We don’t have that same language for lawyers who finish a JD or medical doctors who finish an MD or any of these other folks.

30:30 Gillian: One of the things that I think is important in culture change, and we need to do this internally at the university, for sure, but also I’d like to do it everywhere is to say careers, they’re not linear. People take all kinds of curving paths and I would very much like to see the university and academia in general be a sort of lifelong learning and scholarship partner to people for moments when they’re both in and out of where we are. Now, I recognize I’m in a place of privilege. This is a much easier thing to do in my field than in others. That is what it is. But I think we need to start with changing some of our language and some of our culture around this notion of, if you don’t get that tenure track job or get that right postdoc right after you’ve finished, that the world is ending for you. No, academia will always be here. Go do interesting things, come back, let’s reconnect, and let’s find ways that we can make those boundaries a little bit more porous.

31:28 Emily: Yeah. I really appreciate that. I totally agree with you. I’ll just leave it at that.

31:34 Emily: Sort of along those lines, what about de-stigmatizing these nonacademic careers? You’ve just mentioned language changes, but are there any other ways that people inside and outside academia cannot be looking down on non-academic careers as the consolation prize for not getting a tenure track position, which for the record is definitely not how I feel about them.

31:59 Gillian: Yeah. Well, you know, I will tell you, again, this is a case where being in computing or engineering is a bit easier. My students go off and make two to three times what I will ever make, and more if they get the right stock options, and money goes a long way for de-stigmatizing all kinds of things. That’s one thing to just kind of know, but I think that’s also true in other fields. There’s lots of ways in which you can have a very healthy, productive, happy, and financially successful career outside of the Academy, and that’s an important thing for people to recognize, and to say that you’re not selling out or failing or any of these other things, if you choose to take that kind of path.

32:43 Gillian: The other piece, I think is academics, faculty tend to the people who’ve been really successful in a very particular model of existing. We’re really good at school, the way school was built. The same is true, by the way in K-12. People who become K-12 teachers are often people who were really good at school, and so it’s very hard to reform a system that’s run by people who are really good at that system. We sort of self select for this reinforcing behavior. Some of it is us taking good, long, hard looks at ourselves. And you start to see this, I think, in the undergraduate and master’s curricular reforms that we’re starting to see, where people are recognizing, hey, maybe Sage on the Stage isn’t the best way to teach. And maybe we should be thinking about active learning. Or in the graduate curriculum for master’s students, maybe we should be thinking about modular learning. That you can do pieces of it now and another piece in a couple of years and so on, and put together a collection of experiences that make the right professional degree for you.

33:50 Gillian: I think that gives me hope that if we’re starting to make reforms in K-12, and we’re making reforms in undergrad, we’re making reforms in our professional degrees, it’s only to some degree a matter of time until we can make some reforms in the PhD world and help people to understand that there are different ways to complete a doctorate, and there are different ways to have a career afterwards. It does take activity. It does take bringing back. We have an alumni speaker series here that we bring back people who did their PhDs here, who have exciting, really cool careers, running science museums, or doing policy or running a startup. And we need to show off more of those success stories too.

34:29 Emily: Yeah, I do see, as I visit universities and speak there for the financial stuff, I’m often included in their conversations around this sort of thing. Well, Emily, you’re in entrepreneurship, how do we encourage our students to consider this path as well? And they show me what they’re already doing. It’s percolating. The idea is there. It’s popping up different places. I don’t know how much it still needs to be included actually in the standard path to doctorate rather than just some side extra thing you might engage in. That would be really great.

Best Financial Advice for PhDs

35:01 Emily: Gillian, I love the ideas you’ve presented in this interview. Thank you so much for giving it. I’m just going to conclude with a question that I ask of all of my guests, which is what is your best financial advice for another early career PhD? Could be related to something we’ve talked about today, or it could be something entirely other,

35:19 Gillian: That is a great question, and I thought this was your hardest question, by the way, that I really had to think about. But I think the first thing I would say is get through whatever you’re going through as fast as you can. You will never recover financially from being out of the workforce for however many years it takes you to do a PhD, even if you are the fastest PhD student in the world. The faster you can go time to degree, get done. I always say the only good dissertation is a done dissertation. Get into the workforce as quickly as you can. And the same thing is true for tenure, or for becoming a full professor, for becoming whatever. Yes, these things take time, but just get through them and don’t worry about making it perfect. Each of these things in academia, it’s a pass/fail exam, so pass and move on to the next thing. That’s the first thing I would say.

36:15 Gillian: The second is make sure your summers are paid. Whether you’re a junior faculty member or a PhD student or whatever, that’s a quarter of your year. And I’m always amazed at how many people take it completely unpaid. There are a variety of ways to get it paid. Whether it’s summer teaching, writing grants, internships, consulting, any of these side hustles we’ve been talking about, but the idea that you would lose a quarter of your income at a very young age, when people are in grad school, postdoc-ing, or as assistant professors, those are your prime earning years, and you’re setting yourself up for the future. So figure out a way to get your summers paid. You work for 12 months, so you should get paid for 12 months, is my general thing.

37:00 Gillian: Then the last thing I would say is be mindful of what free labor you give away. Academia is just chock-full, and I know you’ve talked about this on your podcast before, of free labor. We review for free. We give talks for free. We write for free. And that’s okay. That’s a certain amount of the culture and we should be doing certain things voluntarily, but some things you really should start thinking about getting paid for. And you just need to think about that before you decide, am I going to give up however many hours of my time to this? Well, your time is really, really valuable, so treat it like it’s really valuable.

37:36 Emily: I think it goes back to a point you made earlier, which is just asking. If you’re being asked to do some special thing, like speaking, for example, if you were going to agree to do it for free, like you were just talking about why not just ask, Hey, what can you give me an exchange? Pay, expense reimbursement, some other thing of value to you. Just inquire and know that you’re worthwhile. This goes to imposter syndrome as well. Within academia, we tend to feel that we’re not special. Our skills are not that valuable. Everyone else has the same skills and the same knowledge. That is definitely not true, first of all, even inside academia, but definitely, definitely outside, you will be seen as a unique, special thing, as you were talking about earlier, with your PhD and the skills and knowledge that come along with it.

38:19 Gillian: Absolutely. And every time I say to people, whatever number you’re thinking in your head that you’re worth to give that talk or to consult on that project, double it, and you might be close to the number that’s actually what you’re worth.

38:32 Emily: Yeah. Great, great advice again. The worst they’re going to say is no, or maybe they’ll try to negotiate you down, but if you were going to do it for free or little anyway, hey, that’s not too bad. Gillian, thank you so much for joining me on the podcast today. I really, really enjoyed this conversation.

38:47 Gillian: Thank you, Emily. I did as well, and I look forward to hearing many more wonderful podcasts from you in the future.

38:52 Emily: Oh, thank you so much.

Outtro

38:55 Emily: Listeners, thank you for joining me for this episode. PFforPhDs.com/podcast is the hub for the personal finance for PhDs podcast. There you can find links to all the episode show notes, and a form to volunteer to be interviewed. I’d love for you to check it out and get more involved. If you’ve been enjoying the podcast, please consider joining my mailing list for my behind the scenes commentary about each episode. Register at PFforPhDs.com/subscribe. See you in the next episode, and remember, you don’t have to have a PhD to succeed with personal finance, but it helps. The music is stages of awakening by Poddington Bear from the Free Music Archive and is shared under CC by NC. Podcast editing and show notes creation by Lourdes Bobbio.