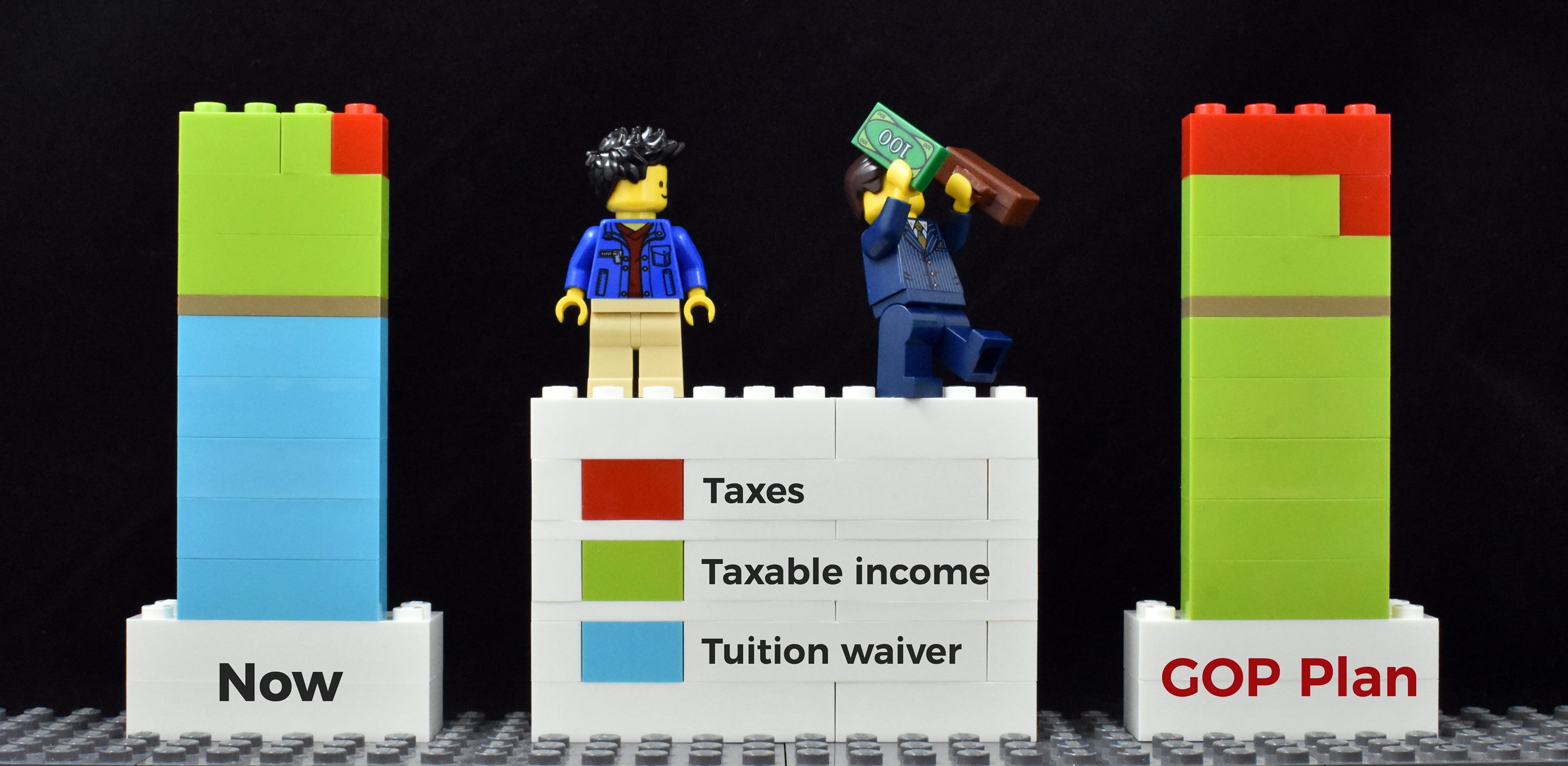

I hope that this is news to no one in the US: Grad student stipends are taxable and so is postdoc income, even if you don’t have taxes withheld or receive an official tax form! You may feel that it’s adding insult to injury to have to pay tax on a lower income, and it is possible that you will not owe any tax if your income is low enough and/or you have enough credits and deductions, but you should still prepare a tax return every year. You need to start from the assumption that all of your income is taxable and use your tax return to reduce your tax burden as much as you can. (This post focuses on US federal taxes for citizens/residents, though international students and postdocs paid in the US will benefit as well.)

A version of this post first appeared on GradHacker.

Further reading:

- Do I Have to Pay Income Tax?

- Grad Student Tax Lie #4: You Don’t Owe Any Taxes Because You Didn’t Receive Any Official Tax Forms

- Grad Student Tax Lie #5: If Nothing Was Withheld, You Don’t Owe Any Tax

Early-career PhDs can turn to one of four sources to prepare their tax returns: themselves, tax software, a relative or friend, or a professional tax preparer. There are pros and cons to each method, and the ultimate choice of which method(s) to use will depend on the complexity of your tax situation, the resources available to you, and your willingness to learn about this important subject.

Further reading: How Do I Prepare My Taxes during Filing Season?

One very important point to know about your tax return is that you are ultimately responsible for its accuracy. That means that whatever method you use, you must check your tax return through to make sure everything is correct. If you have no knowledge of taxes or have been misled by common tax lies told to graduate students, that will be very difficult; identifying all your income sources properly will be challenging and incompetence on the part of your tax preparer may slip by you.

Further reading: Grad Students, Don’t Believe these Tax Lies!

Your tax return is also only as good as the data you provide to it (GIGO!). If you overlook a part of your income, for instance because you received no official tax form for it, it doesn’t matter what method you use – your tax return will be inaccurate. This is particularly a problem for grad students. Take the time before you even choose your method to assess what sources of income you had and what forms you have or have not received for them. You can learn all about how to handle your various sources of grad student and postdoc income in my free tax webinar this week, which will be helpful no matter which method you ultimately use to prepare your tax return.

Further reading: How to Prepare Your Grad Student Tax Return

Receive Your Tax "Cheat Sheet"

Subscribe to the Personal Finance for PhDs mailing list for essential information to help funded US graduate students (citizens/residents) with their federal tax returns

Prepare Your Tax Return Manually

Believe it or not, often the quickest and easiest way to prepare your tax return is to just do it yourself, manually. This is particularly true if you have a simple tax situation, as many young people do. It will probably take an investment of several hours to understand the tax code at a high level and how your income and expenses fit into it the first time you prepare your own tax return. However, subsequent simple or slightly more complicated tax returns should be very quick! (Tip: Instead of using paper and ink, prepare your tax return with the IRS’s Free Fillable Forms.)

Pros:

- If you learn about the tax code well enough to prepare a simple return (and really, all it takes is the ability to follow instructions and do arithmetic), you will go through your life with far more knowledge about income taxes than the average citizen. Taxes do not have to be mystifying.

- Only costs your time.

Cons:

- You don’t know what you don’t know. Without a knowledgeable source keeping an eye on your return, you may miss details such as a credit or deduction that you are eligible for.

- You may make a mistake, either because of your lack of knowledge and experience or simply a math error.

Prepare Your Tax Return Using Tax Software

I’d bet that the majority of early-career PhDs use tax software (e.g., TurboTax, TaxACT, H&R Block) to prepare their returns. It’s a low-cost way of generating a meticulously prepared return. (Tip: The IRS provides free tax software to individuals who earned less than $66,000 in 2017.)

This is the trickiest method to use if you don’t understand your various sources of income well because without tax forms associated with some of the you may accidentally omit or misrepresent them. Software also tends to misinterpret some forms grad students commonly receive, such as categorizing grad students who receive 1099-MISCs as self-employed. Graduate students and postdocs will probably struggle the most with understanding how to enter their non-compensatory pay (fellowships and scholarships), depending on the documentation they receive.

Further reading: Grad Student Tax Lie #2: You Received a 1099-MISC; You Are Self-Employed

Pros:

- Often free, and if not still relatively low-cost.

- Generally thorough and trustworthy if you enter your data correctly.

Cons:

- Can be more time-consuming to answer the software’s thorough questioning than just skipping to the relevant data entry points if you have a simple situation.

- The software is not designed with grad student income in mind, so it can be difficult or confusing to enter non-compensatory pay, depending on the forms or lack of forms your university sends you.

- Perhaps not sufficient for complicated tax situations.

Get a Relative or Friend to Prepare Your Tax Return

It’s fairly common for parents or relatives to (help) prepare children’s tax returns while they are dependents, and it may be tempting to continue that trend into grad school (or beyond!). However, this method suffers from the combined downsides of all the other methods while removing your direct oversight of the situation.

Pros:

- Likely free and a low time investment.

- He/she is probably more generally knowledgeable about the tax code than you are.

Cons:

- While your parents may be competent in preparing their own tax returns as employees or business owners and yours as a college student, they have likely never been exposed to the unusual income reporting strategies employed by universities with respect to their grad students and postdocs.

- You still have to know enough about the tax code to check their work.

Outsource Your Tax Return to a Professional Tax Preparer

I have to admit a bit of bias against using a professional tax preparer as a grad student, unless your life is so complicated that you need one and you have been assured that they know how to handle grad student income. For postdocs and early-career PhDs who receive compensatory pay, professional tax preparers should be quite competent, and probably more needed as your financial life gains complexity. As a person who speaks and writes about personal finance professionally, I have heard many, many horror stories of professional tax preparers bungling grad student income tax returns, causing the grad student to radically over- or underpay their taxes and forcing them to file amended returns once they catch the mistake – and those are just from the grad students who did catch the mistake (or who described the situation well enough for me to catch it)! I’m sure there are also many cases where everything went perfectly with the return, but I don’t tend to hear about those. The point is that grad students are not a common client type for professional tax preparers, so they are not necessarily knowledgeable about the special situation and may not notice the nuances or take the time to learn about them. Again, the responsibility is still on your shoulders to ensure the correctness of the return.

Further reading: How to Work with a Tax Preparer when You Have Fellowship and/or Scholarship Income

Pros:

- Thorough, and possibly the best option for complicated tax situations.

- Low time investment.

Cons:

- Most expensive option unless you use some sort of free clinic.

- As they are usually unfamiliar with grad student taxes (unless you screened for this), you still have to know enough about the tax code to check their work.

Free Tax Webinar for Grad Students and Postdocs

Emily Roberts presented a tax webinar for funded grad students and postdocs (US domestic) on March 9, 2018.

Register for the webinar to receive a replay!

Conclusion

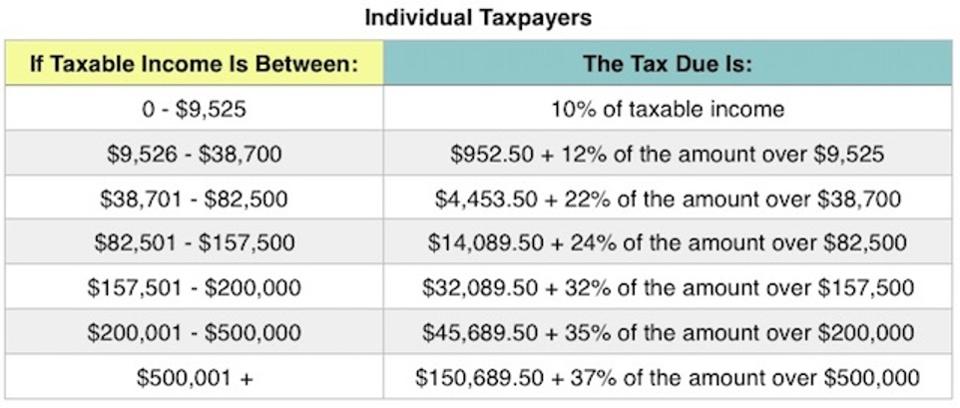

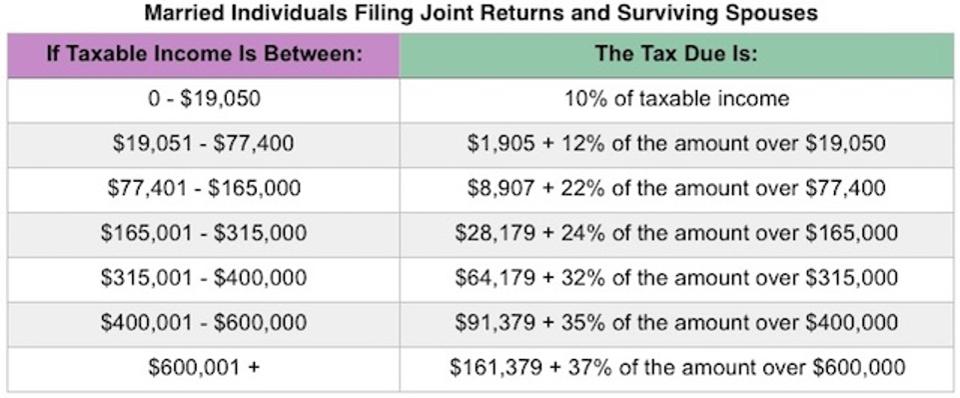

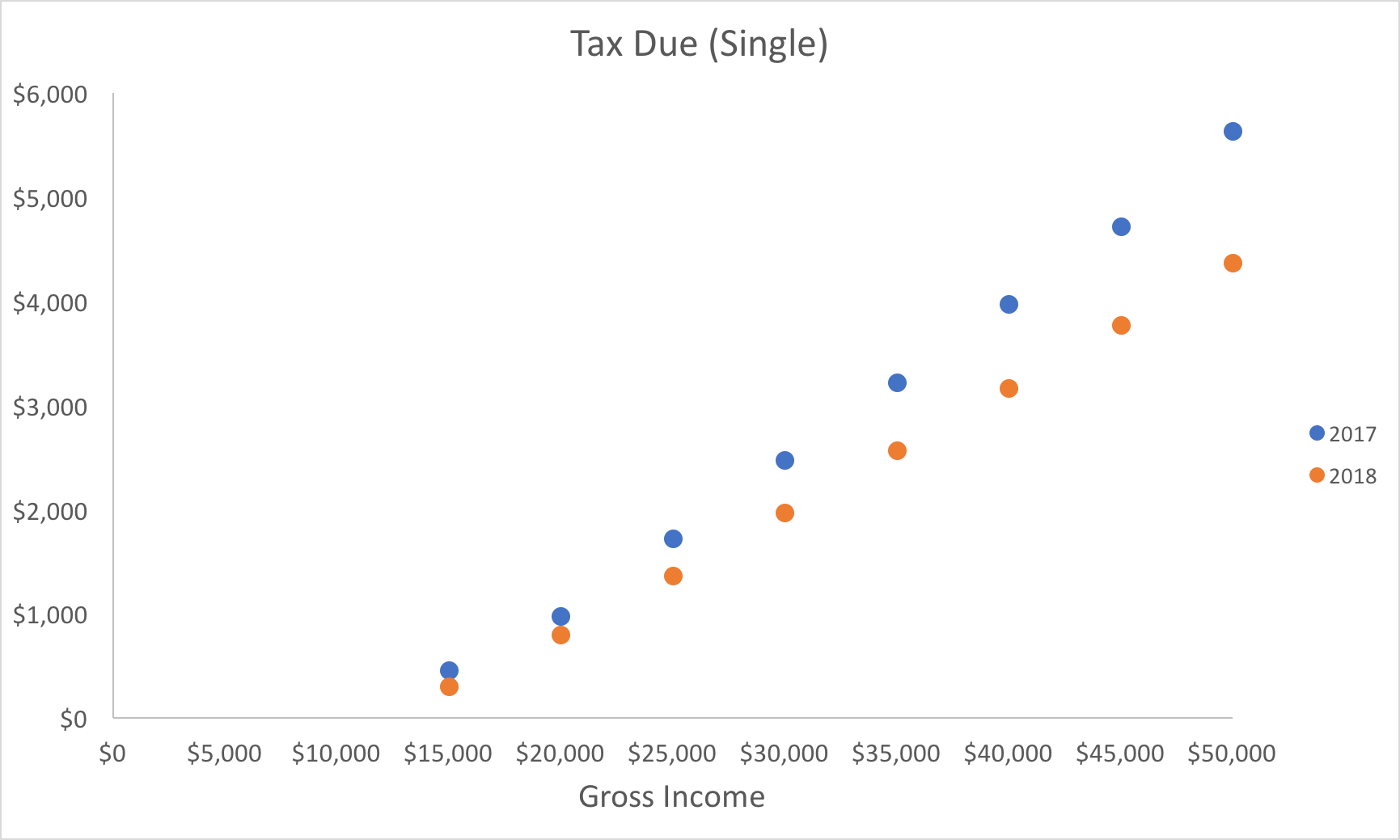

Everyone should know what information should be included in their tax returns, roughly how to calculate their taxable income, and where their income should be reported on a 1040 (or equivalent). This is the basic amount of information needed to generate and check a tax return with respect to your income. I’ll add on here that to be an informed citizen you should also know the difference between a deduction and credit and how marginal tax brackets work.

Further reading: Marginal Tax Brackets, Deductions, and Credits Explained Graphically

If you have a simple life (e.g., not itemizing deductions, not self-employed), it may be worthwhile to invest the time necessary to prepare your return manually this year, because learning that much will be a real time-saver in years to come. Alternatively, you can use tax software in an early year to help you learn about the tax code, and once you’ve grasped the concepts, use them in future years to prepare your return manually.

If you have a complicated life (e.g., itemizing deductions, marriage and children, home ownership, self-employment, investment income, traditional retirement accounts), it’s probably not worth your time to prepare your return yourself with confidence that you haven’t missed anything (unless you enjoy doing it yourself), so paying for tax software or a tax preparer is likely the better choice.

Whatever you do, don’t wait until April 16 to start preparing your taxes using any of these methods!

Further reading: How to Prepare Your Grad Student Tax Return

My Choice

My method of choice during grad school and since has been to prepare my tax return manually and using tax software each year. First, I draft my return myself, which necessitates learning a little something new about the tax code. Second, I use tax software to prepare my return, which alerts me to anything I overlooked that I could incorporate into my manual return. Third, I submit the manual return I prepared – I have more confidence in the correctness of that version!