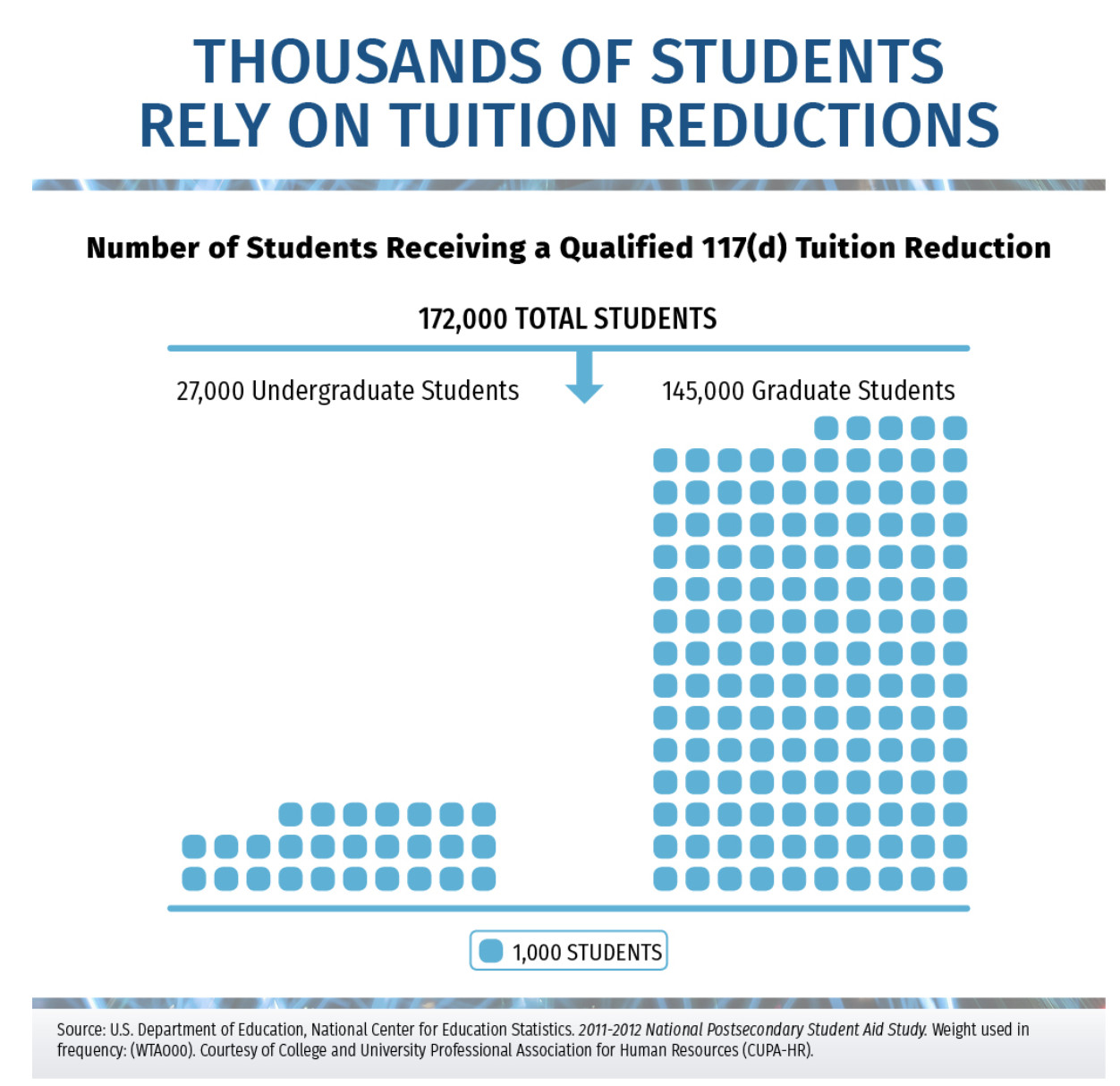

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act has been passed by both the House and Senate and signed by the president, and grad students are rejoicing that their tuition benefits were preserved in the final version. This is really the first opportunity we’ve had to figure out what the changes to the tax code will mean for graduate students and other individuals. In this post I’m running some numbers for a few different income levels and family configurations that are relevant to grad students and postdocs (similar to this article but for lower incomes). The good news is that it does seem that taxpayers at these lower income levels will see a reduction in their tax burdens as long as they take the standard deduction (or their itemized deductions are within about double of the standard deduction).

Download the Tax Spreadsheet

Sign up for our mailing list to receive the spreadsheet I used to write this post, including a 3-question calculator for your own 2018 tax due.

Tax Concepts and Terms

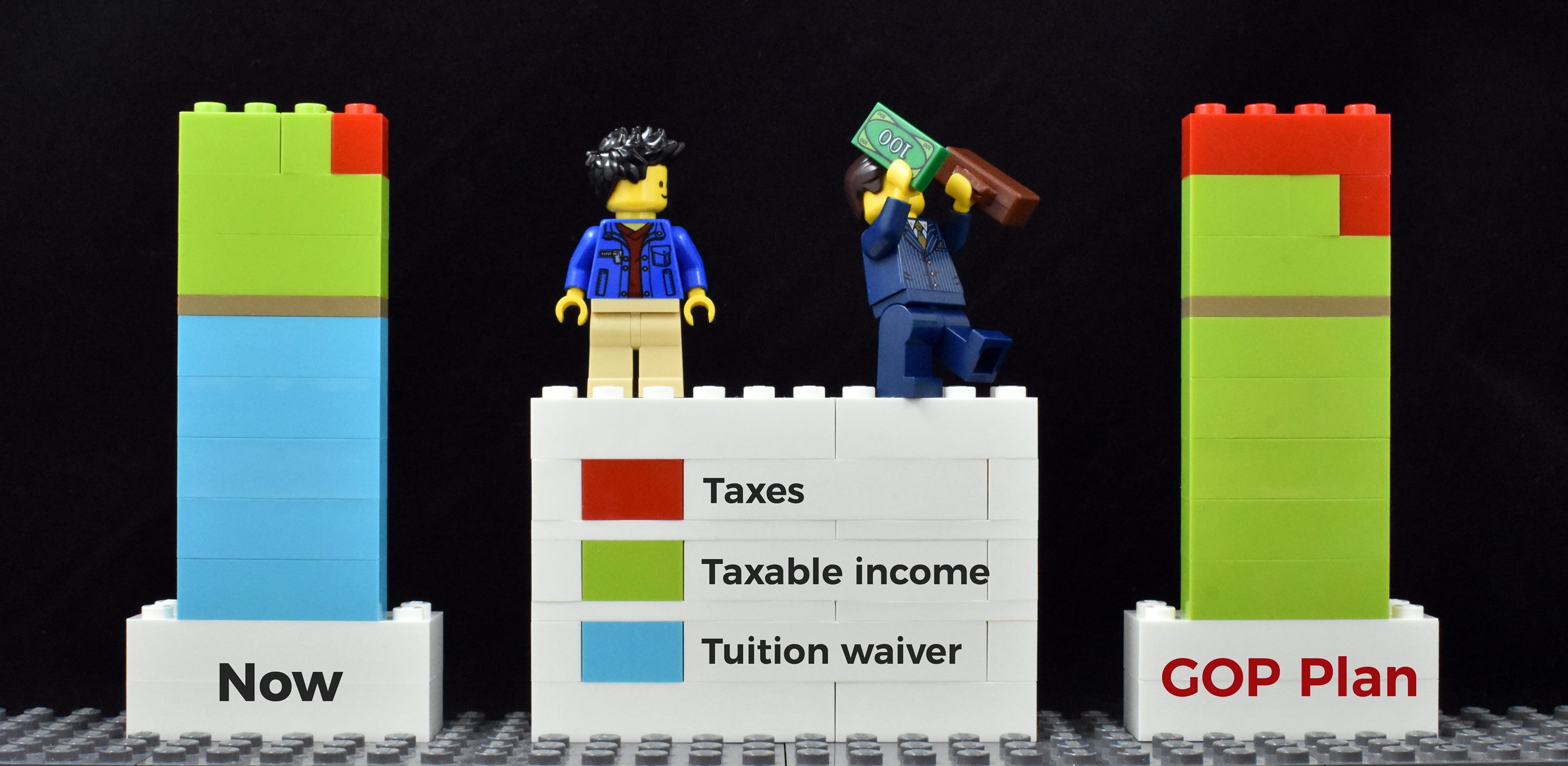

Many Americans don’t realize that our income tax structure is tiered. If your income falls in the 15% marginal tax bracket, for instance, it’s not the case that you pay 15% of your gross income in income tax. Part of your income (the amount that goes into your deductions and (currently) exemption) is not taxed at all. The next chunk of your income is taxed at 10%, and the last chunk is taxed (currently) at 15%. This would continue up the tax brackets if your income were higher.

Further reading: Marginal Tax Brackets, Deductions, and Credits Explained Graphically

A deduction is an amount of money that is excluded from your taxable income. You will choose to take the standard deduction or to itemize your deductions, whichever will give you the larger deduction. There are other deductions that fall outside of the standard/itemized deduction (above-the-line deductions), such as interest paid on student loans (up to $2,500), qualified education expenses if paid out of gross income, and contributions to a traditional IRA. The amount of the deduction multiplied by your marginal tax bracket is the amount that your tax will be reduced due to the deduction. For example, if you are in the 15% tax bracket and apply a deduction worth $1,000, your tax will be reduced by $150.

A credit is an amount of money by which your tax is directly reduced. A credit is worth the same amount no matter what marginal tax bracket you fall in, e.g., a $1,000 credit takes $1,000 off your tax bill. Examples of credits are the child tax credit, childcare expenses credit, and the saver’s credit. Your tax may even be reduced to zero due to credits, and refundable credits allow you to pay negative tax, i.e., receive money instead of paying money at tax time (non-refundable credits stop at a tax liability of $0). Sometimes a credit is applied at a certain percentage, e.g., a 20% credit on an amount up to $1,000 if worth at most $200 but would be less if you spent less on the expense in question.

Changes to the Tax Code in the GOP Bill

There are a few tax policy changes that will affect every American taxpayer, and many more that affect only high-income individuals or individuals in specific scenarios (e.g., taxpayer who previously had a large amount of certain itemized deductions, owners of pass-through businesses). In this post, I’m focusing on changes that will apply to all or many graduate students and postdocs. I have omitted noting at what income levels most of the benefits phase out, instead assuming that graduate students and postdocs will fall under those limits.

In creating this post, I have largely leaned on this great summary of the changes proposed in the GOP tax bill placed side-by-side with the current tax policies. Please note there is a typo in the individual tax rates table ($19,050 is correct, not $19,500).

Standard Deduction

The standard deduction is a set amount of your income that is tax-free. The alternative to the standard deduction is to itemize your deductions, which means documenting one or more types of deductible expenses throughout the year and choosing this deduction type if they add up to more than the standard deduction. (Some of common itemized deductions as of 2017 are medical and dental expenses if over 10% of your adjusted gross income, state and local income or sales tax, property tax, mortgage interest, charitable gifts, and unreimbursed employee expenses.)

One of the stated goals of the GOP with respect to this tax plan was to simplify the tax code, and itemizing deductions is one of the headache-inducing activities that is part of preparing a tax return for some taxpayers (less than 1/3 of households). Raising the standard deduction means that a larger amount of everyone’s income will be tax-free and that many fewer households will have to itemize to receive their largest deduction. However, some types of deductions that previously could be itemized have been eliminated or capped, which could negatively affect taxpayers who heavily relied on them to reduce their tax due. Two of these types of deductions are:

- the state and local income/sales/property tax deduction is limited to $10,000 and

- the mortgage interest deduction is now for loan sizes under $750,000.

Exemptions

In 2017, another amount of income was tax-free for each member of your household, which was your personal exemption. If you are single, you receive one exemption; if you are married filing jointly, you receive two exemptions; you also receive one exemption per dependent child. In 2017, each exemption is worth $4,050.

The GOP tax bill eliminates exemptions in favor of the larger standard deduction discussed above. Because the exemption amount scaled with the number of people in the household whereas the standard deduction is only applied once per household, this change is advantageous for smaller households (single, married couple) and disadvantageous for larger households (married couple with two or more children). However, the expansion of the child tax credit, discussed below, offsets this disadvantage for children up through age 16.

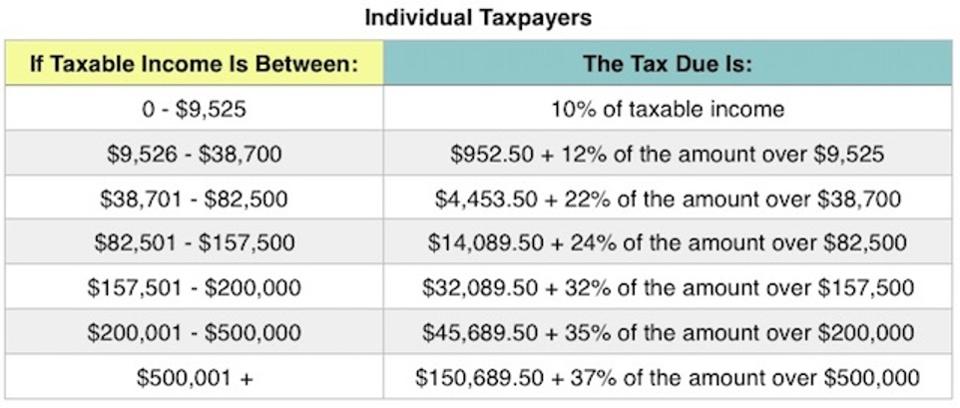

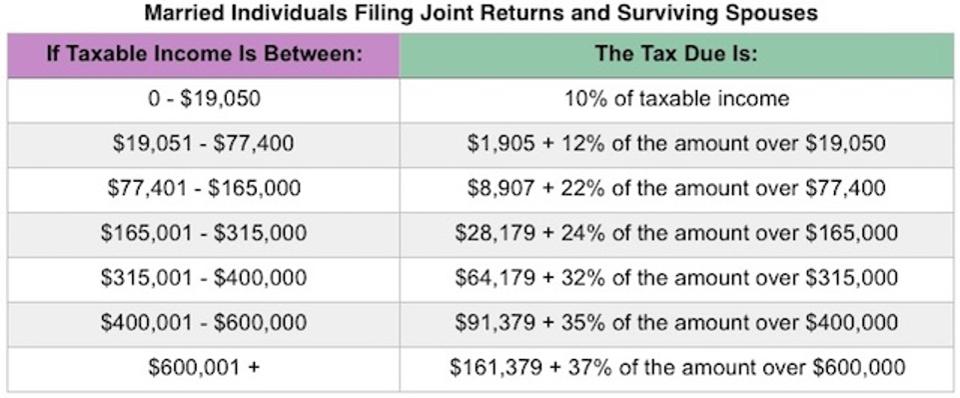

Tax Brackets

The lowest three tax brackets shift slightly under the new GOP plan. Their income ranges remain similar though not exactly the same (they change slightly every year anyway). The 10% bracket will still be taxed at 10%, the 15% bracket will be taxed at 12%, and the 25% bracket will be taxed at 22%.

Keep in mind that when you find your marginal tax bracket (the highest tax bracket your income falls into) in these tables, you will use your taxable income less deductions and exemptions.

Child Tax Credit

The 2017 child tax credit is $1,000 per child for households under certain income limits and is partially refundable for some low-income households. In 2018, the child tax credit will be $2,000 under higher income limits and is fully refundable up to $1,400. The child tax credit applies to children up through age 16.

Income Tax Charts

For Single People and Married Couples Filing Jointly

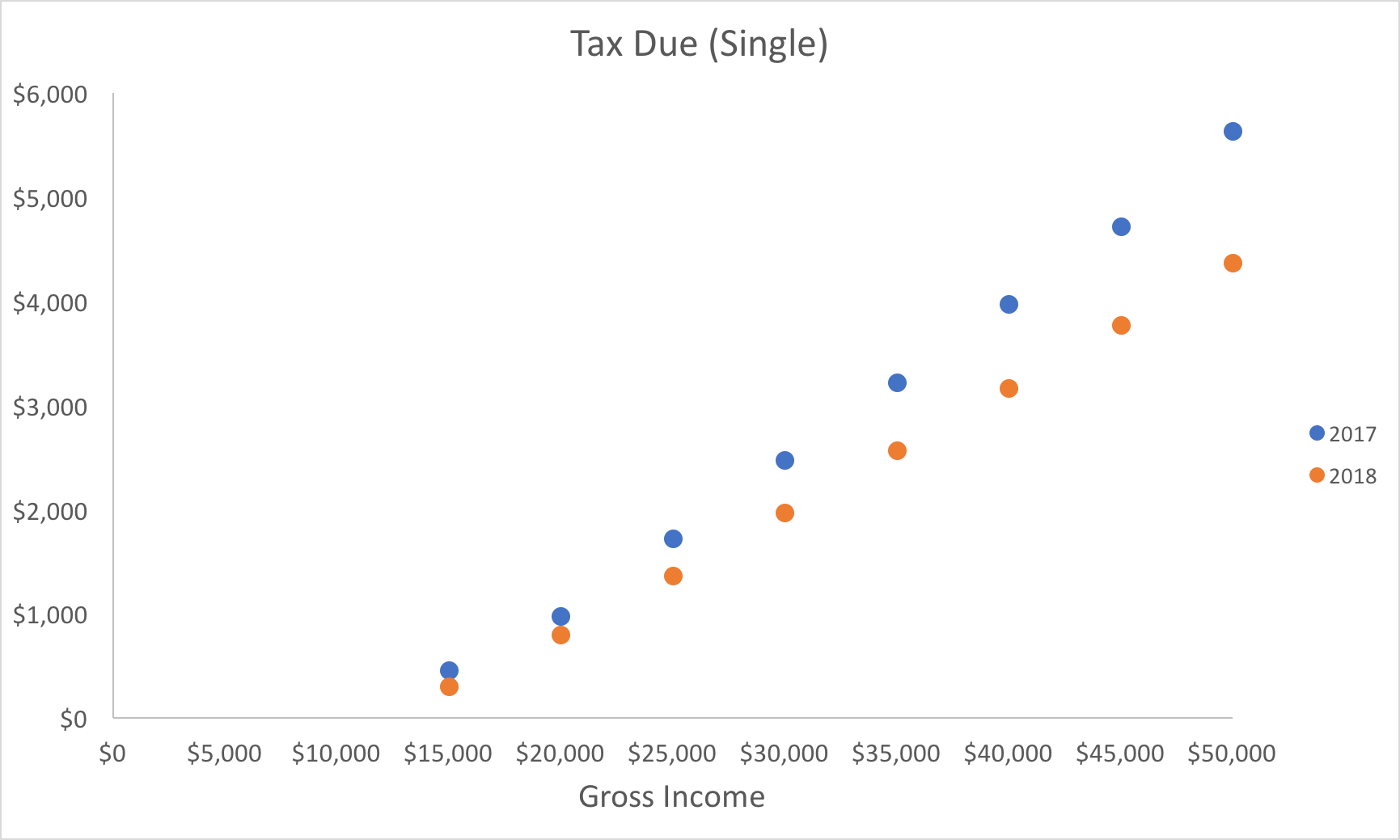

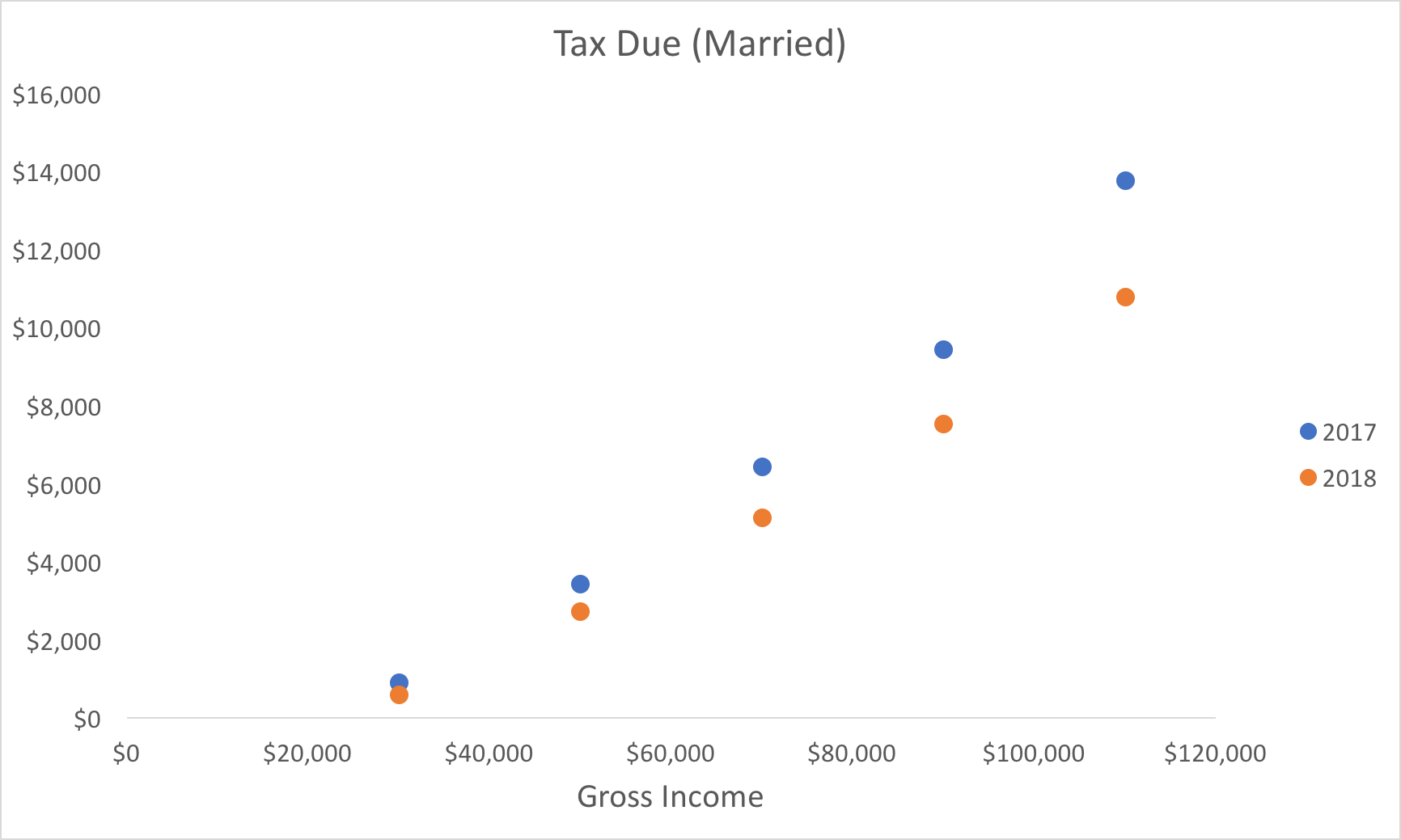

I have created charts of the tax due for individuals and couples with various incomes under the 2017 and 2018 tax laws (assuming no children for now). I assumed the filers would take the standard deduction and no additional deductions (such as student loan interest or qualified education expenses).

Keeping in mind the income ranges of graduate students and postdocs, the ‘single’ table incomes range from $15,000/year to $50,000 with increments of $5,000, and the ‘married’ table incomes range from $30,000 to $110,000 with increments of $20,000.

| Income (x $1,000) | 15 | 20 | 25 | 30 | 35 | 40 | 45 | 50 |

| 2017 Tax Due ($) | 460 | 974 | 1,724 | 2,474 | 3,224 | 3,974 | 4,724 | 5,639 |

| 2018 Tax Due ($) | 300 | 800 | 1,370 | 1,970 | 2,570 | 3,170 | 3,770 | 4,370 |

| Income (x $1,000) | 30 | 50 | 70 | 90 | 110 |

| 2017 Tax Due ($) | 920 | 3,448 | 6,448 | 9,448 | 13,778 |

| 2018 Tax Due ($) | 600 | 2,739 | 5,139 | 7,539 | 10,799 |

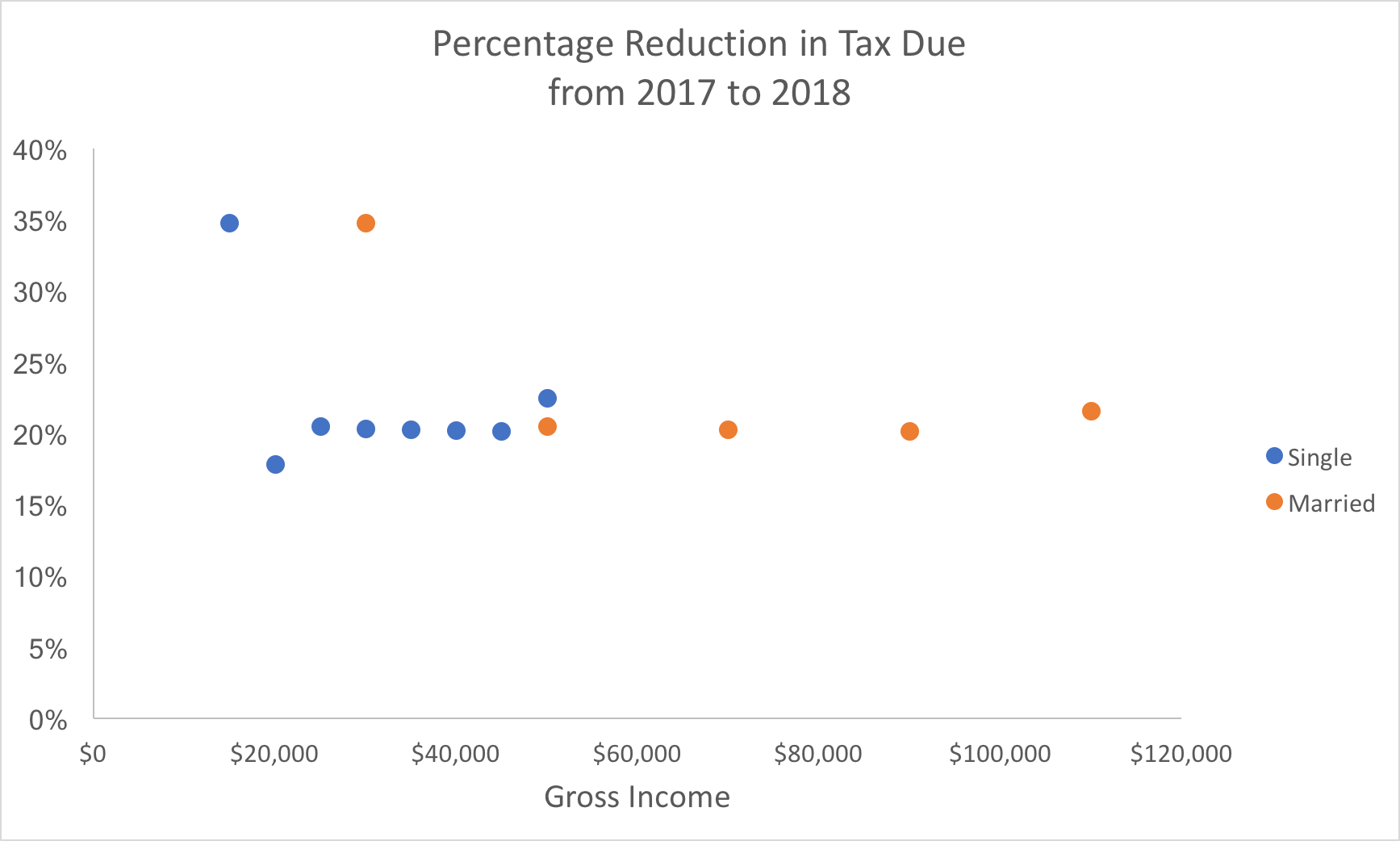

| Income (x $1,000) | 15 | 20 | 25 | 30 | 35 | 40 | 45 | 50 |

| Single Absolute Reduction ($) | 160 | 174 | 354 | 504 | 654 | 804 | 954 | 1,269 |

| Single % Reduction | 35 | 18 | 21 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 23 |

| Income (x $1,000) | 30 | 50 | 70 | 90 | 110 |

| Married Absolute Reduction ($) | 320 | 708 | 1,308 | 1,908 | 2,978 |

| Married % Reduction | 35 | 21 | 20 | 20 | 22 |

Under the above assumptions, graduate students and postdocs across these income levels will see a reduction in their tax burdens between 20 and 35%.

Download the Tax Spreadsheet

Sign up for our mailing list to receive the spreadsheet I used to write this post, including a 3-question calculator for your own 2018 tax due.

Adjustments for Children

In 2017, if you have a dependent child under the age of 17, you can take the child tax credit for $1,000 per child. A credit is worth the same across the tax brackets because it directly reduces your tax due. In addition, you can also take an exemption for your dependent child (possibly up to age 23). In terms of the effect on your final tax burden, if you are in the 10% tax bracket the exemption is worth $405.00, if you are in the 15% tax bracket the exemption is worth $607.50, and if you are in the 25% tax bracket the exemption is worth $1012.50.

In 2018, the child tax credit has been expanded to $2,000 per child, but only up through age 16.

Download My Spreadsheet

You can download the spreadsheet I used to make the above charts with the complete tables. I have also included a sheet where you can estimate your own tax due by answering three questions.

Download the Tax Spreadsheet

Sign up for our mailing list to receive the spreadsheet I used to write this post, including a 3-question calculator for your own 2018 tax due.

Do Your Own Calculations

This post skips over many of the nuances of the current and new tax law, so it does not substitute for plugging your numbers into a calculator (once full ones become available) or the math you will do in preparing your tax return. It is only intended to give an estimate of the tax due for ordinary wage earners (and, I presume, fellowship recipients) in the income ranges relevant to graduate students and postdocs. If you have automatic withholding on your paycheck, you should see changes to your take-home pay in early 2018. If you file quarterly estimated tax, your first payment is due in mid-April, so you have a few months for the IRS to adjust Form 1040-ES and to calculate your new tax burden.