Update: Please fill out this survey on how your university handles your tuition benefit. I and some colleagues are trying to determine which universities use the method slated for elimination in the House bill.

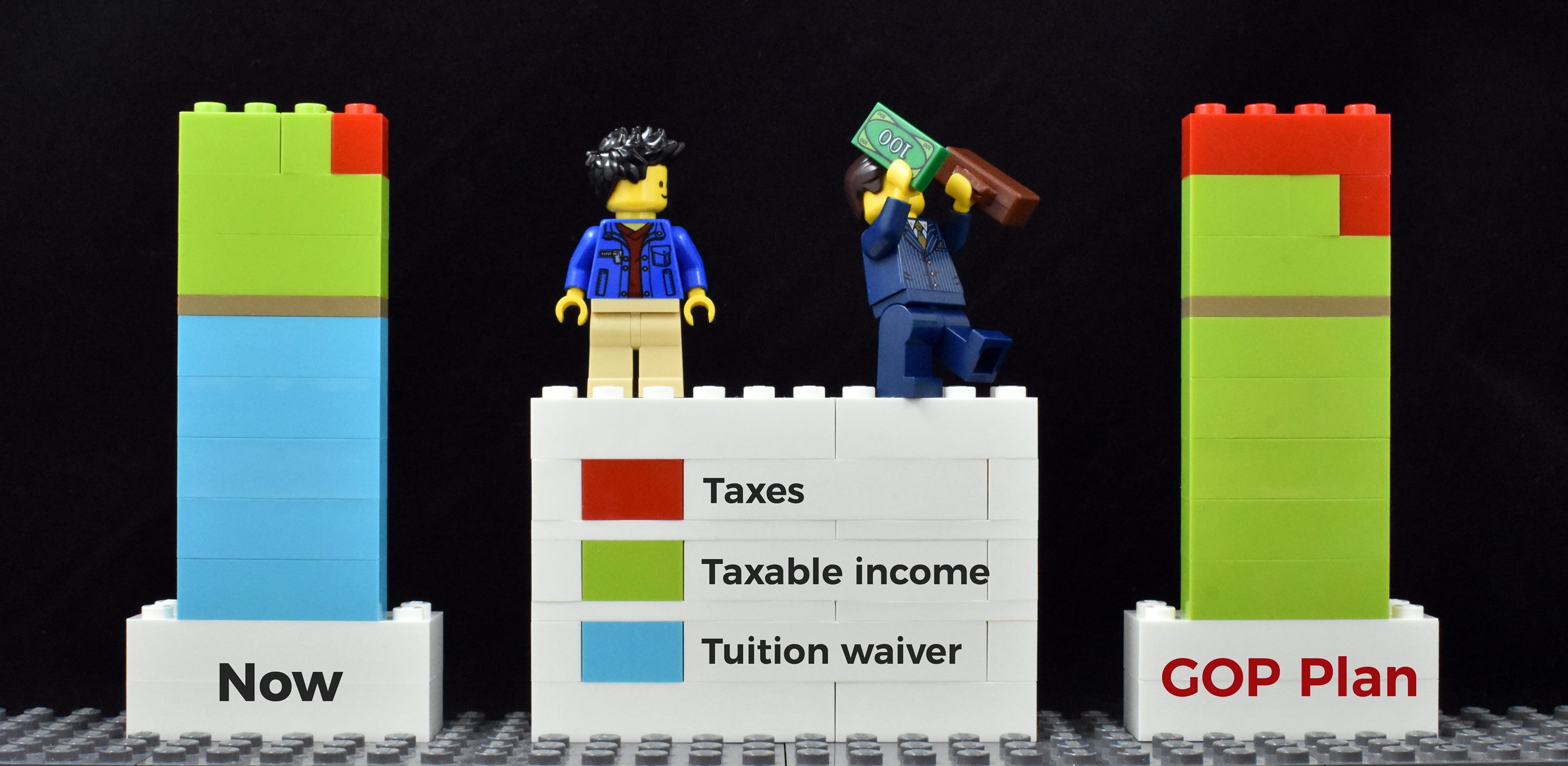

The House GOP released their proposed tax bill (The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act) last week. Over the last several days numerous media outlets have covered the effect the bill would have on graduate students who receive “tuition waivers,” and graduate students have started organizing responses. Students at Carnegie Mellon, for example, calculated how much more tax students in various schools would have to pay if they lost their tuition tax benefits.

Here are articles I read that are most focused on the bill’s effect on graduate students:

- The GOP Tax Plan Will Destroy Graduate Education

- Grad Students Are Freaking Out about the GOP Tax Plan. They Should Be

- The Republican Tax Plan Could Financially Devastate Graduate Students

- The GOP Tax Bill Could Be a Disaster for PhD Students

- ‘Taxing a Coupon’

When I first started reading about this issue, I got the impression that under the bill all graduate students would see a large increase in their tax burden based on the reversal of their previously untaxed tuition benefits. The strongly worded headlines above certainly imply that graduate students would see such an increase in tax that continuing their educations would be impossible.

However, after spending many hours reading the current tax code, Publication 970, the proposed bill, university websites, news articles, and social media, I think that there is some confused information and hyperbole in the early reports, or at least what the articles are saying is being taken out of context by scared graduate students. However, I haven’t fully figured out what the implications of the new bill are, and I have several questions that are still outstanding. This post details my current thoughts on the issue. My intention is to calm some of the extreme fear I’m observing (in those who do not need to be so fearful), while still imploring you to voice your opposition to the proposed changes to tuition benefits and other effects on higher education funding.

To be clear, I don’t wish to see the net (after-tax) income of any graduate students drop as a result of tax reform. I believe all graduate students who have assistantships or who receive fellowships should be paid at bare minimum a living wage. Honestly, that’s a pretty low bar that not all universities currently meet. If a new tax bill is passed that increases the tax burden on graduate students, the universities should take steps to ensure that current graduate students’ net pay does not decrease. Otherwise, they do risk losing students they have already invested in or putting the students who remain in such a precarious financial position that they are distracted from their research.

But before you panic about your own personal finances, I think you should look carefully at how exactly you are paid. Not all graduate students will be negatively affected by this direct changes made by this bill (should it pass); I think the effects are going to be less widespread and less extreme than what the current coverage and conversations imply.

However, I do think you should lobby your representatives to maintain (more of) the current education benefits. (You just may not be able to use yourself as an example.) This is a moment in which graduate students and academics can band together to advocate for ourselves and academic research in general, whether or not we will be affected in our individual finances. The end of this post lists a few action steps. If the bill does pass, there will be more advocacy to be accomplished within your state and at your university to mitigate the bill’s effect on your and your classmates’ bottom lines.

A disclaimer: I’m using a lot of secondary source information for this post. I did read sections of the current tax code and the proposed bill, but as I’m not a policy wonk or lawyer I freely admit that they are difficult for me to parse. If you find any mistakes, wrong conclusions, or omissions, please let me know so I can update the post. Accuracy is very important to me.

What Tuition Benefits Do Graduate Students Currently Receive?

We have to get technical for a bit here because the devil is in the details. I’ve seen students and articles using the terms “tuition waiver” and “tuition remission,” which do not appear in the proposed bill, Publication 970, or (as far as I’ve read) in the current tax code. So I’m going to avoid drawing conclusions from the common terms that are used in academia in favor of figuring out what is actually in the current tax code and bill.

There are three broad tuition benefits that I’ve known graduate students to use:

- tax-free scholarships, fellowships, and tuition reductions (the most common)

- the Lifetime Learning Credit

- the Tuition and Fees Deduction

Basically, if you have any qualified education expenses such as tuition and required fees (the precise definition is not consistent), you can get some kind of tax break.

The proposed tax bill eliminates the Lifetime Learning Credit and the Tuition and Fees Deduction in favor of an expanded American Opportunities Credit (which can only be used in the first five calendar years of post-secondary education and therefore pretty much doesn’t apply to graduate students). This change will increase the tax burden on the students who previously used the Lifetime Learning Credit or Tuition and Fees Deduction, but that hasn’t been the main concern I’ve seen expressed by graduate students in the media.

The big kahuna here are the tax-free scholarships, fellowships, and tuition reductions. There are no monetary limits on these benefits like there are on the Lifetime Learning Credit and Tuition and Fees Deduction. Currently, any scholarship or fellowship that goes toward paying your tuition or qualified fees is not taxed. Also not taxed is any “tuition reduction” you receive. A tuition reduction is the difference between the sticker price tuition and the tuition you are charged.

Scholarships, fellowships, and tuition reductions are all lumped together in Chapter 1 of Publication 970 and Section 117 of the tax code, so I’ve never paid much mind to which is which exactly since they were all tax-free. But the proposed tax bill specifically targets one benefit and not the other.

Which Tuition Benefits May Be Lost and Which May Be Maintained?

The benefits are delineated in Section 117 of the tax code as qualified scholarships (117(a-b)) vs. qualified tuition reductions (117(d)). The tax bill proposes “striking subsection (d) of section 117” (p. 96), presumably leaving intact the other sections.

117(a-b): Gross income does not include any amount received as a qualified scholarship by an individual who is a candidate for a degree at an educational organization described in section 170(b)(1)(A)(ii). The term “qualified scholarship” means any amount received by an individual as a scholarship or fellowship grant to the extent the individual establishes that, in accordance with the conditions of the grant, such amount was used for qualified tuition and related expenses.

117(d): Gross income shall not include any qualified tuition reduction. For purposes of this subsection, the term “qualified tuition reduction” means the amount of any reduction in tuition provided to an employee of an organization described in section 170(b)(1)(A)(ii) for the education (below the graduate level) at such organization… In the case of the education of an individual who is a graduate student at an educational organization described in section 170(b)(1)(A)(ii) and who is engaged in teaching or research activities for such organization, [the above] paragraph shall be applied as if it did not contain the phrase “(below the graduate level)”.

How Can You Tell What Type of Tuition Benefit You Receive?

Section 117(d) explicitly applies only to university employees, which in the case of graduate students means teaching or research assistants. So if you are currently not a student-employee, i.e., you do not receive a W-2 at tax time, your tuition benefit should not change (which further argues for the superiority of fellowship funding over assistantship funding). (An analysis from a Berkeley student concurs this point.) However, I think it’s pretty unusual for a PhD student to complete her degree supported only by fellowships and training grants; most students serve as TAs or RAs for at least a few (if not all) of their semesters.

For student-employees, the question becomes: How do you know if your tuition and fees are paid by a qualified scholarship or a qualified tuition reduction? I do not have a good answer, and I’m hoping a reader can provide one. I don’t know that there is a different reporting mechanism, for example, for qualified scholarships vs. tuition reductions. (The 1098-T, if one is issued, should reflect the required tuition and fees charged to the students and the scholarships applied, but I don’t know if or how a tuition reduction would be reflected in that document. A qualified tuition reduction would not appear on a W-2.)

The best suggestions I can make at this point to figure this out for your situation are:

- Re-read your offer letter and any employment contract you have with your university for the keywords “tuition reduction” vs. “scholarship,”

- Check your Bursar/Cashier’s/Financial Aid account for the term “reduction,” and

- Ask administrators at your university whether you receive a tuition reduction (e.g., the Bursar/Cashier’s office), pressing them to consult the university attorneys if they can’t point you to an answer.

How Common Is the Use of Section 117(d) for Graduate Students on Stipends?

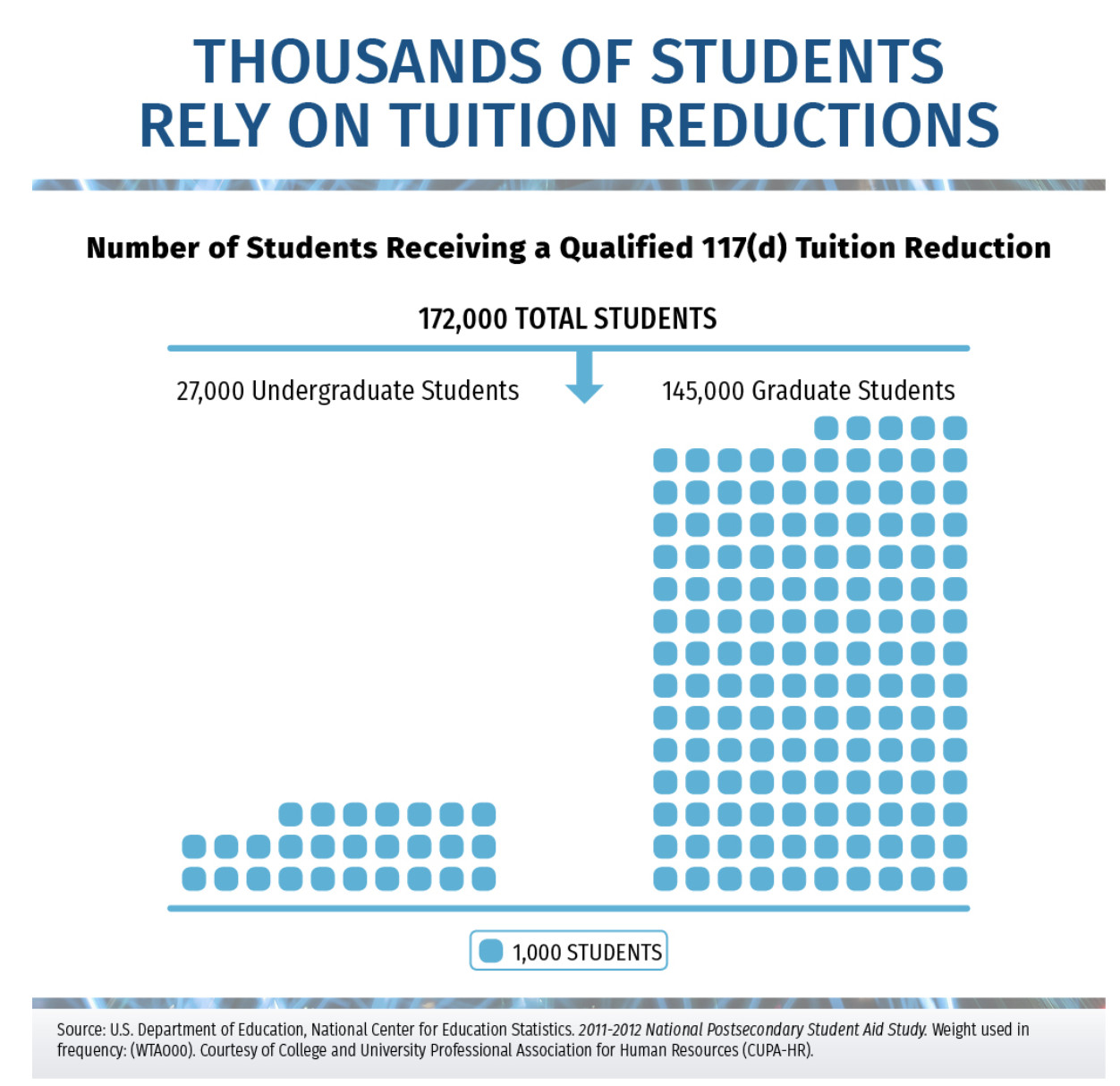

One of the popular articles circulating by Vox pulled a figure from an infographic sheet the College and University Professional Association for Human Resources. (CUPA-HA also created this summary bulletin on Section 117, which makes it clear that section 117(d) is used by many types of university employees beyond TAs and RAs). In turn, the infographic is based on the 2011-12 National Postsecondary Student Aid Study.

The relevant number that the Vox article and CUPA-HA cite is that 145,000 graduate students benefit from section 117(d). (I was very curious about how they determined this number as it seems so wonky and specific to help with the unanswered question above, but the version of the 2011-12 National Postsecondary Student Aid Study that I could access did not contain this data. So I would like to dive further into those numbers, but I’m stuck for now.)

Taking the 145,000 students at face value (50% of whom earn more than $50,000/year, so not exactly traditional graduate students who would be unable to continue their studies due to an increased tax bill), what fraction of the total graduate student population is that?

I couldn’t find the answer directly, but the recent NSF survey of earned doctorates cites 54,070 doctorates awarded in 2014. Approximately 50% of PhD students never complete their degrees, so I would peg the current number of doctoral students in the US between 250,000 and 500,000. The 145,000 figure probably also includes master’s students, making the relevant pool of graduate students in the US even larger.

145,000 students using section 117(d) is certainly a large fraction of that total, but definitely not everybody as was my first impression. (Keep in mind, though, that an individual student may use section 117(d) during part of her time in graduate school, so the number using it at any given time is less than the total number who use it at any point.)

As far as how the proposed legislation will affect students at individual universities goes, I have two data points so far (please let me know if you’ve received a definitive answer from your university!):

The Dean of the Graduate School at Cornell released a statement regarding their policies. It reads in part:

Cornell University does not rely on 117(d) for favorable tuition-related tax treatment of funded graduate students, who are considered students, not employees, at Cornell.

Because Cornell pays graduate students reasonable compensation for teaching, research, or other services they provide to the university, Cornell graduate students receiving a tuition scholarship are receiving a qualified scholarship as described under sections 117(a), 117(b), and 117(c) of the current tax code, provisions which are not proposed for repeal in H.R. 1. Thus, the proposed repeal of section 117(d), if passed into law, will not have an impact on how Cornell graduate students’ tuition scholarships are handled.

While the stipend for graduate students may be taxable under the current tax code, the tuition scholarship is not, and would not be affected by repeal of 117(d). As H.R. 1 is written, Cornell graduate tuition scholarships will continue to be treated as qualifying (tax free) scholarships under 117 (a), thus, there would be no change from current tax law that treats these tuition scholarships for students as tax free.

I graduated from Duke University three years ago, and my understanding was that my tuition and fees were paid by scholarship. In my Bursar account, for example, I would see a tuition charge posted and then a payment posted on my behalf. I assume that payment was a scholarship, and I don’t know how a tuition reduction would have appeared. My recollection was (I think) confirmed by this page that discusses how graduate students are supported: “Full or partial scholarships: Cover tuition and fee expenses.” Tuition reductions are not mentioned. So I think that Duke students, like Cornell students, also do not depend on section 117(d) for their tuition tax benefit.

A Tentative Guess as to the Impact of the Proposed Bill

Here is my intuition on the matter, and I’m curious if it bears out or not. I formed it based on the scantest impressions and it involves far too much extrapolation.

I think perhaps tuition reductions are used mostly by public institutions, whereas qualified scholarships more so by private institutions. Therefore, eliminating the non-taxable status of tuition reductions may disproportionately affect public school students.

However, the large numbers I’ve seen in the media of the “devastating” effect of the tax bill on graduate students are based on tuition charged at private universities and by public universities for out-of-state students. (State policies regarding residency status for the purpose of in-state tuition vary. In some states, students are eligible for in-state residency after the first year. In others, such as Georgia, out-of-state students maintain their status for the duration of their degree.) Public, in-state students might see their taxes increase by hundreds of dollars or a thousand dollars, not the multiple thousands or $10,000+ I’ve seen quoted (except perhaps in the year when they are considered out-of-state students), which is if the full tuition and fees at some private universities were taxed at 12 or (partially) 25%.

I think that if tuition reductions are being used by private universities, they will have more wiggle room to pivot to either compensate their students differently or to pay them more. Well-funded departments and universities may also be able to increase their students’ pay to make up for the additional tax due (perhaps a one-time grant in the first year for out-of-state public university students). Therefore, I hope that the negative effects of the bill will be smaller and more limited in scope than currently anticipated.

Steps You Can Take to Advocate for Higher Education

All that notwithstanding, this is the time for advocacy. I fear that if the proposed tax bill passes as written, the additional tax burden will fall largely upon the students who are least financially secure, namely students in underfunded departments at public universities (earning, for example, less than $20,000/year). A $1,000 increase in their tax bill could easily push them into (further) credit card or student loan debt because their finances are so precarious to begin with. Even if your university does not rely on section 117(d) or you have a fellowship, please stand up for your fellow PhD students who are at risk.

- The NAGPS Call Congress Day is TODAY, November 8. You can find all the details about action steps on their Facebook event and website. You can still use their talking points as guidance after November 8.

- If you are represented by a union, participate in their lobbying efforts, or consult them on how to organize your own.

- Talk with your peers about advocacy steps you can take as a group at the national level and, if this provision of the bill passes, at the state, university, and department levels.

- Tell your family members, neighbors, college friends, mentors, etc. about this issue and ask them to advocate for PhD students as well.

In all of this, if you are currently taking advantage of a tuition reduction I encourage you to use your personal numbers (by what absolute amount and percentage your tax bill would increase) like this student did. These numbers are shocking and powerful.

Do you benefit from a tuition reduction or is your tuition paid by scholarship (or both)? Do you expect your tax burden to increase or decrease if the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act passes as written and by how much? How are you advocating for section 117(d) to remain in the tax code?

Join Our Phinancially Distinct Community

Receive 1-2 emails per week to help you take the next step with your finances.

Texas A&M University is a public institution. The ledger says my tuition was “payed” by 4 “TAMU related 3rd party payments.” I know the department had something to do with that as I know who needs to do the paperwork to make that happen. That money showed up on my 1098-T field 5: Scholarships or Grants. I wonder if the definition of what goes in that field would be illuminating if section 117(d) applies or 117(a-c) applies.

I did a video on how it effects me personally for my 2015 taxes, and I checked both ways there: youtu.be/u-Sqk5zC4FE. I’m in a different more difficult boat this year.

Thanks for your comment and linking to your video!

It sounds like those may be scholarships, but I’m not sure yet until I hear from more people on how tuition reductions are reported. Perhaps you can check with your university?

It would be my understanding, given the 117(d) requirement that the university pays for the reduction/waiver, that your situation would not qualify as a “qualified tuition reduction”. If it’s actually a tuition waiver/reduction, paid for by an outside source, it would not qualify for exclusion from income. Since it’s not reported as income, it would almost have to be via the definition of a qualified scholarship

One error in your analysis. An out of state student is forever considered an out of state student for the duration of their entire enrollment. There may be a state that has a generous exception to this rule but I doubt it. Otherwise we would have out of state second year MBAs, second and third year law students and med students in years two through four all getting bargain rate in state tuition rates. Even being an employee of the university and paying taxes will not change ones status, if you start out out of state, you stay that way. And the nature and specialization of PhD programs generally means most grads are from out of the state.

Thanks for your comment! To which state(s) are you referring that don’t offer in-state tuition to PhD students after 1 year (or so)? I do think the general rule is that students after one year can establish residency if they are financially independent (perhaps that is the difference between PhD and professional students?), but perhaps there are some exceptions. For example, I heard from my friend who went to Georgia Tech for his PhD from out of state that his status changed after a year, and I know at the University of North Carolina students can petition for residency after a year (though I think it’s not always granted).

This article is mostly for prospective grad students but it does say: “It takes around 12 months for a grad student to establish residency in state, but some states are more lenient.”

https://www.usnews.com/education/best-graduate-schools/paying/articles/2016-06-15/get-set-up-for-in-state-tuition-as-a-grad-student

The rules for residency are all over the map, as is the willingness of a university to help students get in-state status. In Tennessee, while the rules seem onerous, the universities will go out of their way to help you establish residency (and for most out of state students, that also means making it their tax home–a bonus given there’s no state income tax).

I’m also a Georgia tech student (who actually grew up in Georgia but spent a year working out of state before starting at GaTech) who has been in the PhD program over 5 years and am still paying out of state tuition. According to the documents I read residency in Georgia during enrollment does not count towards getting in state tuition at any public university including GaTech. (No student shall gain or acquire in-state classification while attending any postsecondary educational institution in this state without clear evidence of having established domicile in Georgia for purposes other than attending a postsecondary educational institution in this state.)(http://www.usg.edu/policymanual/section4/C329/) So it seems your friend got lucky but

GaTech policy is not normally that lenient on residency.

Thanks for your comment! Yes, the link you gave is quite clear. Perhaps the policy has changed recently; my friend started grad school at GT over 10 years ago. I actually spoke to another friend about this who started his PhD at UCLA 10 years ago; he changed his residency to in-state in his first year, but based on his sibling’s more recent experience starting grad school he thinks the state has made residency changes more difficult in the intervening years. I wonder if this is part of a wider pattern.

I did undergrad in Texas and am in grad school in Virginia, and both states make it very hard to claim residency if you are a full-time student. Honestly, I’m surprised Georgia Tech and UNC will let second-years apply for in-state residency status given that they are also very competitive public universities. However, at UVA, tuition goes down as you go farther in a PhD program to recognize that fewer of your hours come from professor-led lectures, though at different rates for in-state vs out-of-state.

Looking at my financial aid statements, I see both “tuition adjustments” and the tuition remission both categorized as “waivers”, so I’m not entirely sure what to make of that. And to make it more confusing, my department also has internal (non-competitive) fellowships it will put students on to help smooth over gaps in research assistantship funding, but those are taxable.

Thanks for your comment!

Would you please comment with a link on the residency requirements for UVA (and in Texas if you can find them) if you know of one? I’d like to read more about this!

Yeah this is a confusing issue. “Adjustment” sounds like “reduction” maybe… Does it look like you were charged the full out-of-state tuition amount and then were given these waivers to cover it all? And does either the remission or adjustment correspond to the difference between in and out of state tuition? Thanks for checking this out if you have a moment!

I think that the money provided to graduate students cannot be considered tax-exempt scholarship funding, since it usually comes with the condition of employment (research or teaching services. 117(c)c says “subsections (a) and (d) shall not apply to that portion of any amount received which represents payment for teaching, research, or other services by the student required as a condition for receiving the qualified scholarship or qualified tuition reduction”. 117(d) then has a statement exempting graduate students from paying taxes on tuition waivers, even though they are employees rendering services. If 117(d) is repealed, it doesn’t seem obvious that graduate student tuition can fall under 117(a).

I think what this section refers to – and this is based on reading examples provided by the IRS from just after this legislation was passed – is the stipend rather than the money that pays tuition. The big change from the 1986 tax reform was that stipends became included in gross income. So the IRS started to differentiate between money that was payment for services like teaching and research and money that paid qualified education expenses, with the former starting to be taxed and the latter remaining tax-free. So the portion of a “scholarship” that is payment for services is the stipend and it is compensatory pay (in academia we don’t even refer to it as a scholarship anymore). But it’s not talking about the money that pays for tuition, etc. even if the person also has a work requirement like a TA or RA position. So the tax-free status (subsections (a) and (d) does not apply to “that portion of any amount received which represents payment for teaching, research, or other services,” but it still does apply to the portion that pays qualified education expenses. The work requirement condition, to me, is a bit of a red herring, because really what’s at issue is the stipend.

But I think the best argument for the legitimacy of tuition scholarships is that universities such as Cornell and Notre Dame use them, as clarified by their statements to their students http://pfforphds.com/tuition-tax-results/.

I haven’t had anyone at your university take our survey yet; would you consider doing it if you have a few minutes? http://pfforphds.com/tuition-tax-survey/