Perhaps you’ve never put it in these terms, but you’ve likely experienced some degree of financial fear of missing out (financial FOMO) during your PhD training, such as when you:

- peruse Instagram photos from your friend’s latest vacation

- read about young professionals maxing out their 401(k) contributions

- receive a LinkedIn notification about your college classmate’s recent promotion

- congratulate a friend on buying a home

Becoming a PhD-level researcher takes a lot of time. The PhD itself is usually at least five years long (the average in the US is closer to 8 years), and then you might do a multi-year postdoc (or two) before you finally get a Real Job, inside or outside of academia. And in all that time – for many students, the bulk of their 20s and into their 30s – you see your friends and former classmates walking down your Road Not Taken. Namely, they’re earning more money than you. Perhaps you start thinking that even though you’re both aging at the same rate, they are progressing financially while you are not. And that gives you financial FOMO.

PhD-Induced Financial FOMO

You can’t live the same lifestyle on a grad student stipend or postdoc salary that you could on a real job salary. Frugality is going to be your constant companion until you’re done with your training! So there are some obvious day-to-day sacrifices that you make to pursue your academic goals.

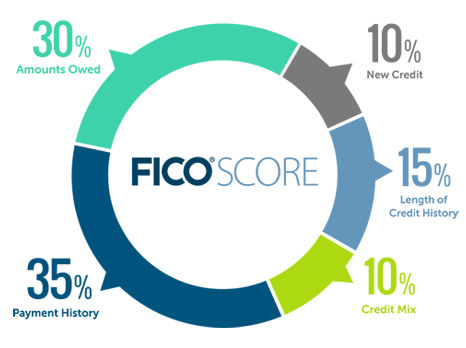

On top of that, if you’re becoming savvy about personal finance, you know the importance of paying off debt and beginning to invest early in life. As a PhD student, not only do you lack the income to save tens of thousands of dollars each year, you don’t even have a 401(k) or 403(b) in which to save it! Some postdocs have access to 403(b)s, but have a similar problem on the income side as PhD students when it comes to saving.

Further reading: My Realistic Earnings Expectations Push Me to Save Aggressively

So yes, objectively, you are almost certainly missing out on some income that you would have earned if you had worked a real job instead of going to grad school. But that does not mean you should let financial FOMO overwhelm you or cause you anxiety.

Below are five simple steps to take to fight financial FOMO through mindset changes and good financial practices.

Don’t Dwell on Facebook/Instagram/Pinterest Jealousies

“Comparison is the thief of joy.” – Theodore Roosevelt (attributed)

“Don’t waste your time on jealousy. Sometimes you’re ahead; sometimes you’re behind. The race is long, and in the end, it’s only with yourself.” – Baz Luhrmann

If looking at other people’s picture-perfect (for the amount of time it took to snap the picture!) homes, vacations, toys, etc. bums you out, stop looking! It’s a waste of time and detrimental to your mental health.

End Grad School with A Higher Net Worth than the One You Started with

When it comes to building wealth, how much money you earn doesn’t matter; what matters is how much money you put to work for you. A 10% savings rate on a $30k/year salary amasses more than a 0% savings rate on a $1M/year salary. So don’t worry about people who have higher salaries – unless you talk about it, you have no idea if they are actually building wealth.

To the extent that you are able (and still live a reasonable lifestyle), use part of your income to repay debt or invest. Investing even modest amounts of money during your training can have a massive effect on your net worth in your golden years. If you can end grad school with a higher net worth than you started, even by a small amount, that is financial progress.

Free Email Course: Investing for Early-Career PhDs

Sign up for the mailing list to receive the free 10,000-word email course designed for graduate students, postdocs, and PhDs in their first Real Jobs.

Practice Percentage-Based Budgeting

The best thing I did to alleviate my financial FOMO during grad school was to practice percentage-based budgeting. Basically, instead of paying attention to the amount of money I was putting into my Roth IRA (my primary financial goal), I tracked its percentage of my gross income. My initial goal was to save 10% of my gross income, which sounds a heck of a lot better than $200/month. By slowly inching up the percentage over time, my husband and I increased our combined savings rate to 17.5% by the time we finished our PhDs, and then we continued to save at that percentage rate as our income increased as we transitioned out of academia.

The great thing about percentage-based budgeting (loosely based on the Balanced Money Formula) is that it scales with your income. So if your overall goal in life is to save X% of your income (or pay off debt, etc.), practice that during your training as well as after, even though the amounts of money will be quite different. You’re creating the firm habit of saving, which will serve you very well now and throughout your life.

Build Your Career (Don’t Just Work on Your Dissertation)

Just because you’re a grad student or postdoc doesn’t mean you’re not also a career-building professional. You do not have to limit your professional growth during your training to academia-sanctioned activities like publishing papers and attending conferences (though you should definitely do those). You can also gain real work experience and network, which increase your ability to land that first post-PhD Real Job.

Two excellent activities to engage in are a side job and networking.

Side job: Your eligibility for side work depends on your contract or the terms of your fellowship, so check on that and consider your advisor’s stance on outside work before you jump into anything. You will fight your financial FOMO if you can devote a few hours each month or each week to a part-time or freelance job that gives you new skills or an opportunity to demonstrate your existing skills, a larger/better-quality network, and additional money.

Further reading: Can a Graduate Student Have a Side Income?

Networking: Networking doesn’t have to be unnatural or awkward. One easy-access high-quality network is to befriend (or at least be friendly with) and keep up with your peers who exit academia before you, e.g., your labmates/groupmates, other trainees in your department, peers you interviewed with on your prospective students visit weekends, and people you meet socially through the university. (Keep in mind that some people who are “behind” you in training – undergrads, master’s students, and PhD students who started after you – may exit academia before you!) You will have indirect access to the networks they build when they get Real Jobs.

Remember What Brought You to Grad School

Perhaps the most powerful step you can take to fight your financial FOMO is to do some introspection. Identify and reflect on your top life values. Something within those values pushed you to pursue your PhD training. Perhaps it was: making a difference, curiosity, achievement, learning, growth, creativity, service, or knowledge.

Your values are what you hold most dear, presumably more dear than lifestyle elements or wealth (unless those also play into your values). You must find something about your research or career path more compelling than the perks that a Real Job would confer. If not, your issue is not financial FOMO, but rather you need to re-evaluate why you are continuing your training at all.

You can also take some time to enumerate the good things that grad school or your postdoc have brought into your life, such as friends and colleagues, your city, and gratifying (elements of) work. A gratitude journal is a great way to shift your mindset away from experiencing financial FOMO.