In this episode, Emily explores the topic of credit: what is it, why it matters, how to establish it, how to improve it, and when you can stop thinking about it so much. Near the end, she also reveal the biggest credit killer that she sees among the PhD community and how to overcome it. As ever, the content is tailored to the PhD experience of finances in the US, including that of international students, postdocs, and workers.

Links Mentioned in the Episode

- Investopedia definition of creditworthiness

- What Is a Good Credit Score? How Do I Get a Good Credit Score? [Nerdwallet]

- Sam Hogan’s Zillow Profile

- Council of Graduate Schools, Financial Education: Developing High Impact Programs for Graduate and Undergraduate Students

- Personal Finance for PhDs Community

- How to Up-Level Your Cash Flow as an Early-Career PhD

- How to Pay Off Debt as an Early-Career PhD

- Hub for the Personal Finance for PhDs Podcast

Intro

Welcome to the Personal Finance for PhDs Podcast: A Higher Education in Personal Finance. I’m your host, Dr. Emily Roberts.

This is Season 10, Episode 6, and I don’t have a guest today, but rather I’m exploring the topic of credit: what is it, why it matters, how to establish it, how to improve it, and when you can stop thinking about it so much. Near the end, I also reveal the biggest credit killer that I see among our community and how to overcome it. As ever, I have tailored the content in this episode to the PhD experience of finances in the US, including that of international students, postdocs, and workers.

I’m eager to devote time to this important topic because many PhDs, especially those who grew up outside the US or are from underprivileged backgrounds, don’t have credit or have poor credit or are concerned about their credit. If you have good credit, it’s not something you have to pay much attention to. But if you have poor credit or no credit, it can really hold you back financially and limit your life choices.

The credit bureaus start tracking our financial actions as soon as we start taking any. For many of us, that starts when we’re minors or college students, long before we may have the financial acuity to safeguard and foster our credit. Very sadly, some children and adults are victims of financial fraud, which can destroy your credit through absolutely no fault of your own, and it can be very difficult and painful to rectify.

I expect listeners of this episode to run the gamut, from PhDs and graduate students with great credit to those with poor credit to those with no credit. You will all find great information in this episode, including what steps you should take to establish or improve your credit, if necessary, and some reassurance as to when you can put your credit out of your mind.

What Is Credit?

Asking the question “What is credit?” seems like a basic place to start this episode, but I actually had to search a little harder for a good definition than I was expecting. In fact, the best definition I found was for the term creditworthiness rather than credit, and it’s from Investopedia.

“Creditworthiness is… how worthy you are to receive new credit. Your creditworthiness is what creditors look at before they approve any new credit to you. Creditworthiness is determined by several factors including your repayment history and credit score.”

Basically, credit is a tool that lenders use to evaluate how risky you are to lend to, which affects whether whether they will work with you at all and what interest rate you’ll be offered. This evaluation is based on your past use of credit.

All of your credit-related activity is tabulated in your credit report. Actually, you have multiple credit reports, each prepared by a different credit bureau. There are three main credit bureaus: Equifax, Experian, and Transunion. In theory, they are all working off of the same information.

The information that is included in each of your credit reports is 1) personally identifiable information, such as your name, social security number, and address; 2) lines of credit and payment history, which is all of the loans and credit that have been extended to you and your repayment history with each, going back approximately seven years; 3) credit inquiries, which is a record of each time your credit is viewed by a potential lender; and 4) public record and collections, which is a record of bankruptcies or bills that have gone to collections because you neglected to pay them.

Your credit reports are used to calculate credit scores. You actually have many credit scores calculated in different ways by different bodies for different purposes. The most popular credit score for mortgages and similar loans is the FICO credit score. A close second is the VantageScore. We’ll return in a few minutes to how those scores are calculated and what they mean.

The main points I want you to take from this section are that your credit scores are based on your credit reports, which are records of all of your credit-related activity.

Why Credit Matters

Why should you or anyone else care about your credit or your credit score in particular? You can see that your credit is based on how you’ve treated your debt and some other financial obligations in the past, and it was developed to help lenders asses whether they should lend to you under the assumption that you will behave in the future as you have in the past. So clearly your credit matters if you are trying to take out a loan, like a mortgage or car loan, or a line of credit, like a credit card.

Rather strangely, your credit score is also often referenced when someone wants to quickly judge how financially responsible you are. Landlords, utility companies, and insurance companies often access credit scores, and some employers and even governments do as well. It is a big leap to assume that how you’ve treated debts in the past is predictive of general financial responsibility in the future, and I think it’s quite unfair.

People who have no credit are often quite financially responsible because they have managed to run their lives without the use of debt, but that’s not reflected in their nonexistent credit score. Also, credit you may have had in your home country does not translate to the US; you have to start over. And for anyone with poor credit, the actions and/or circumstances that created that low credit score are not ones that will necessarily be repeated in the future. You can change your financial behavior on a dime, but it takes a long time for your credit score to catch up.

The Equal Credit Opportunity Act of 1974 ostensibly prohibits discrimination based on race alongside other factors, but in practice there is a credit gap. A recent study by Credit Sesame found that 54% of Black Americans had no credit score or a poor or fair credit score, while only 41% of Hispanic Americans, 37% of white Americans, and 18% of Asian Americans had the same. The credit gap stems from the Black-white wealth gap, homeownership gap, employment gap, and income gap, and perpetuates the wealth gap and homeownership gap.

The credit gap is caused by systemic problems, and systemic solutions are warranted. However, in this episode, I’m going to focus on what you can do as an individual to impact your own credit score.

What is a good credit score and how is it calculated?

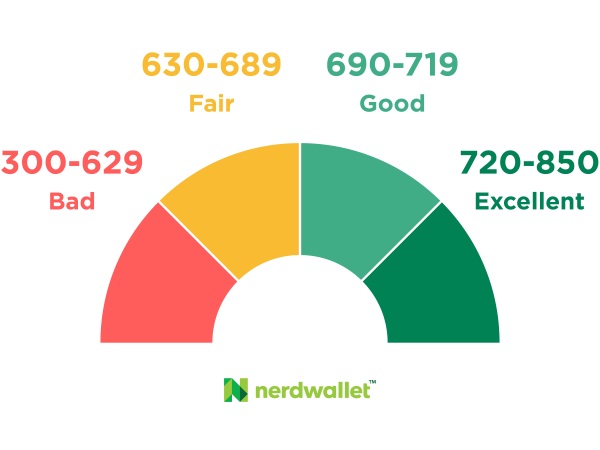

The FICO credit score and VantageScore range from 300 to 850. According to a lovely Nerdwallet graphic linked in the show notes, a score of 720 to 850 is considered excellent, 690 to 719 is good, 630 to 689 is fair, and 300 to 629 is poor. For another reference point, a FICO credit score of 760 and above will get you the best interest rates on a mortgage.

While the exact algorithm for calculating FICO credit scores is proprietary, we know that 35% of the FICO score is based on payment history, 30% on amounts owed, 10% on new credit inquiries, 15% on the length of your credit history, and 10% on the mix of credit. We’ll get into what actions you can take in each of these areas to improve your credit score momentarily.

How do I establish credit?

Before we get there, I want to speak to those of you who do not have any credit history in the US. I do think it’s worthwhile to establish credit history and a credit score if you are not yet financially independent. A good credit score is useful as a renter and a virtual necessary when taking out a mortgage.

As I explained earlier, credit is self-referential. To have credit, you must have had credit. So how do you get your foot in the door?

The simple and free way to do so is to take out a secured credit card. This is a special kind of credit card designed to help people establish credit. You turn over a deposit, which becomes your line of credit. You borrow against that line of credit and then pay it back. After about six months, you should have a credit score and be able to move on to more conventional debt products, if you want to. These credit cards are often marketed as student cards.

Alternatively, if you have a family member who is very responsible with credit, you could ask to be added as an authorized user on one of their credit cards. In this way, their good credit sort of rubs off on you. You don’t actually have to even have or use your authorized user card. Just make sure that the person you ask to do this pays off their credit card balance in full every statement period. As soon as your credit score is established and high enough, take out your own credit card to establish your independent credit history. As I learned from Sam Hogan, a mortgage originator with PrimeLending (Note: Sam now works at Movement Mortgage) and an advertiser with Personal Finance for PhDs, in one of the live Q&A calls we’ve held, your credit score may look good with only an authorized user card in your history, but you won’t qualify for a mortgage on that alone.

There are two other solid ways to establish credit, but they are not usually free, and therefore I suggest you only undertake one of them if it is very financially important to you to establish the highest possible credit score quickly. That’s not usually necessary, so these are sort of extreme steps.

Method #1 is to take out a loan with a bank, sometimes specifically called a credit builder loan. This is an installment loan, so it’s a good complement to the revolving line of credit you likely already have with a credit card. It’s not enough to take out the loan, but rather the point is to make the minimum payments consistently to demonstrate that you are capable of repaying debt responsibly. The cost here is the interest you’ll pay throughout the repayment period, so you should shop around for the best rate available to you. You could also consider doing this with a student loan if you are a student, but since the loan won’t go immediately into repayment, I’m not certain it will have as positive an effect on your score as a credit builder loan would. Plus, student loans are not dischargeable in bankruptcy, if it came to that, so that’s a strike against them in comparison with a bank loan.

Method #2 is to pay a service to report the payments you are already consistently making to the credit bureaus. For example, the service might report your rent payment, which would not normally be included in your credit report. The cost here is the fee for the service, so again, shop around. You won’t have to keep the service up indefinitely, only long enough to qualify for another debt product.

This last tactic of reporting rent payments to credit bureaus and having them be calculated into credit scores is, from what I can tell, the top method being pursued to address the credit gap. A few landlords are starting to report rent payments to the credit bureaus on behalf of their tenants for free. The newest versions of the FICO and VantageScore algorithms do take rent payments into consideration, but most lenders still rely on older versions of the algorithms.

How do I improve my credit?

Now that we’ve covered establishing credit, let’s go deep into how to improve credit. Please take note from the outset here that improving your credit score is a long game. You must practice good credit behavior consistently for years. Since the length of your credit history is taken into account, you really can’t attain a top credit score until you’ve been using credit for at least a handful of years.

I’m going to give you at least one suggestion from each category that goes into the FICO credit score. Don’t be shocked when one or two of the suggestions contradict each other!

35% of the FICO score is based on payment history. This is the key category. Make your payments on time and in full every time. For years.

30% of the FICO score is based on amounts owed. Pay down your debt. Pay off your debt. For a specific hack, keep your credit card utilization rate low. Your utilization ratio is the balance you owe across all your credit cards divided by the sum of your credit limits. You should keep this ratio below 30% or ideally below 10%. Please note that your utilization ratio can be viewed at any point in your statement period. So even if you pay off your credit cards in full every period, as you should, having a high utilization ratio at some point earlier in the period will still ding your score. You can keep your utilization ratio low without changing your spending by 1) requesting credit limit increases across all of your cards, 2) applying for new credit cards to increase your overall credit limit, and 3) paying off your cards multiple times each statement period instead of just at the end.

10% of the FICO score is based on new credit inquiries. Don’t apply for any new loans or lines of credit. I warned you that some suggestions would be contradictory!

15% of the FICO score is based on the length of your credit history. Basically, you just need to let time pass. It helps to keep your oldest credit card open indefinitely and to close newer accounts if you want to close any. If you haven’t opened a credit card yet, choose one without an annual fee to be that first card.

10% of the FICO score is based on the mix of credit. Specifically, this means having both revolving lines of credit, like credit cards and home equity lines of credit, and installment loans, like a mortgage, car loan, student loan, etc. If it was really important to you to improve your credit score and you didn’t have any installment loans, you could take one out, like the credit builder loan I mentioned earlier, but it will cost you.

Another great, general step to take is to check your credit reports for accuracy once per year through annualcreditreport.com, which is the government-sponsored website where you can order one credit report per year from each credit bureau. During the pandemic, that limit was increased to once per week. Keeping tabs on your credit reports is part of your basic good credit behavior.

Credit killers

Now I’d like to explore the main credit killer that I see PhDs and particularly graduate students falling into. And it’s not student loans! Believe it or not, as long as you’re current on your payments and your balance isn’t inordinately high, student loans are kinda good for your credit score. No, the big credit killer, and killer of your finances overall, is credit card debt.

According to the Council of Graduate Schools’ recent report, Financial Education: Developing High Impact Programs for Graduate and Undergraduate Students, 85% of graduate students have a credit card. Forty-five percent of those carry a balance on their cards, with 9% only making the minimum payment.

Everyone listening to this podcast episode knows that finances in graduate school are challenging at best. We can all understand how readily an emergency or unexpected expense could result in a carried balance on a credit card. But, I implore you, instead of accepting that your credit card balance will be with you until and through graduation, get aggressive about ridding your balance sheet of this most toxic kind of debt.

Ideally, you would pay your balance off by increasing your income and/or decreasing your expenses and throwing all available cash—outside of a starter emergency fund—at the debt. Depending on how high that balance is, you may not have to make these sacrifices for long.

If it is absolutely impossible for you to increase your income or decrease your expenses before you finish graduate school, you could at least mitigate the negative effects of your credit card debt. If your credit card debt resulted from the hard reality that your stipend is insufficient to pay for basic living expenses, please consider taking out a student loan to pay off the past debt and supplement your income going forward so you stay out of credit card debt. While it’s not great to be in student loan debt either, at least you can defer the payments until after you graduate. If your credit card debt resulted from an unexpected expense that is unlikely to recur, you might consider paying off your credit card debt with a personal loan from a bank or with a balance transfer credit card. That way, you can at least get a break on the interest you would have paid while you’re paying down the balance.

If you’d like to learn more about increasing your cash flow and paying down debt, please join the Personal Finance for PhDs Community at PFforPhDs.community. Inside the Community, you will find the recordings of two workshops I gave in August, titled How to Up-Level Your Cash Flow as an Early-Career PhD and Whether and How to Pay Off Debt as an Early-Career PhD. After working through the materials, you will have a plan for how to handle your credit card balance in the short and long term.

When your credit doesn’t matter

The final credit topic I’ll address in this episode is when your credit doesn’t matter and when it does. Once you have attained a great credit score of approximately 740 or above and you keep up your good credit habits, you don’t need to pay much attention to your credit. Keep paying your bills on time and in full, use your credit cards as you would debit cards, chip away at your debt, and check your credit reports for accuracy once per year. You don’t have to actively work on increasing your credit at that point—with one exception. If you are planning to take out a loan in about the next year, it would behoove you to get a little more protective about your credit. I’m particularly speaking about taking out a mortgage, but this would also help you with a car loan or similar. For example, you might stop opening credit cards months or a year in advance of applying for your new loan so that you don’t have any recent hard credit inquiries. You might pay off a smaller debt in its entirety. You might pay special attention to your utilization ratio. Above all, when you start working with a mortgage loan officer, listen to that person’s advice about what to do regarding your credit. They might instruct you to make absolutely no changes. I know that Sam Hogan, the mortgage originator I mentioned earlier, advises his clients all the time about their credit in the lead-up to taking out a mortgage. If you are looking to take out a mortgage in the near future and you want to work with someone who understands PhD income, please reach out to Sam over text or a call at 540-478-5803.

Conclusion

I hope this episode was instructive for you and clarified what steps, if any, you should take regarding your credit as a graduate student, postdoc, or PhD with a “Real Job!”

Outro

Listeners, thank you for joining me for this episode!

pfforphds.com/podcast/ is the hub for the Personal Finance for PhDs podcast. On that page are links to all the episodes’ show notes, which include full transcripts and videos of the interviews. There is also a form to volunteer to be interviewed on the podcast. I’d love for you to check it out and get more involved!

If you’ve been enjoying the podcast, here are 4 ways you can help it grow:

- Subscribe to the podcast and rate and review it on Apple Podcasts, Stitcher, or whatever platform you use.

- Share an episode you found particularly valuable on social media, with a email list-serv, or as a link from your website.

- Recommend me as a speaker to your university or association. My seminars cover the personal finance topics PhDs are most interested in, like investing, debt repayment, and effective budgeting. I also license pre-recorded workshops on taxes.

- Subscribe to my mailing list at PFforPhDs.com/subscribe/. Through that list, you’ll keep up with all the new content and special opportunities for Personal Finance for PhDs.

See you in the next episode, and remember: You don’t have to have a PhD to succeed with personal finance… but it helps!

The music is “Stages of Awakening” by Podington Bear from the Free Music Archive and is shared under CC by NC.

Podcast editing by Lourdes Bobbio and show notes creation by Meryem Ok.