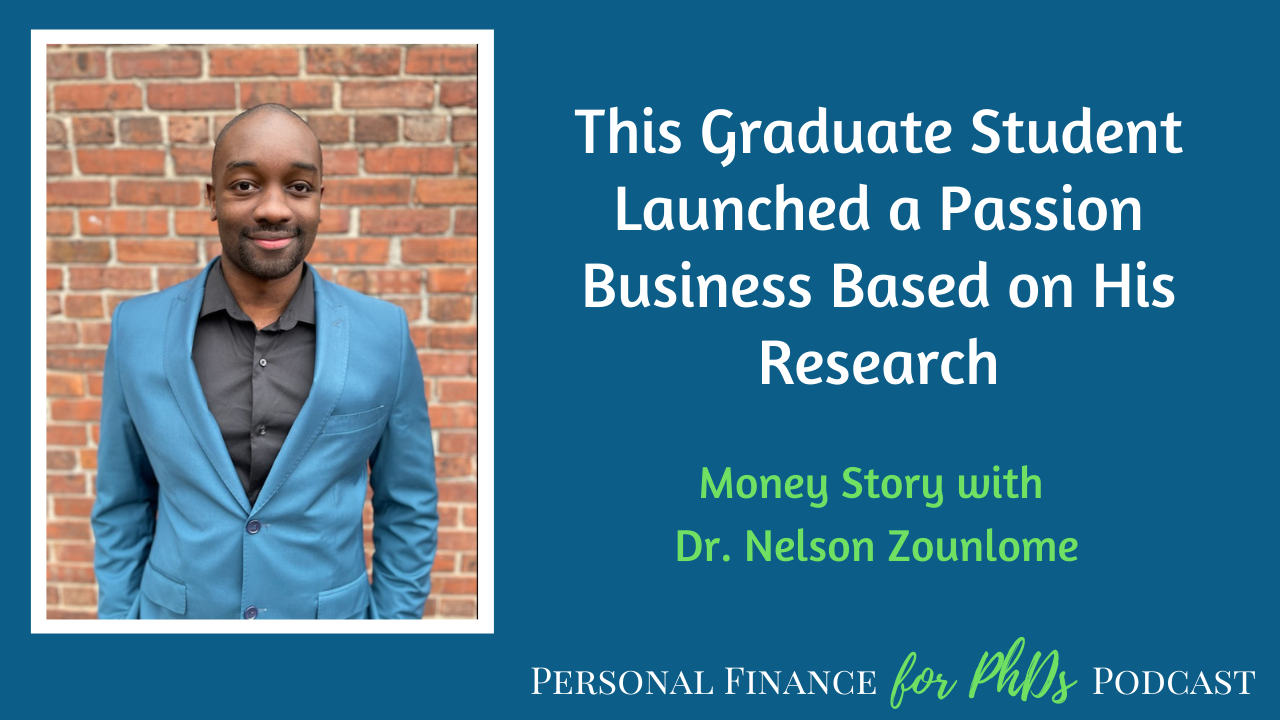

In this episode, Emily interviews Dr. Nelson Zounlome, a recent PhD in counseling psychology from Indiana University and assistant professor at the University of Kentucky. Nelson started graduate school with a negative net worth, but over the six years of his PhD he increased his net worth to nearly six figures, including investments in both a Roth IRA and taxable brokerage account. Nelson practiced intentional frugality, particularly with respect to his large, fixed expenses and high-ticket purchases. However, what really moved the needle in Nelson’s finances was increasing his income, both through winning an external fellowship and starting a business. Nelson and Emily discuss in detail how his business complements his research and became an asset during his recent hiring process.

Links Mentioned in the Episode

- The Millionaire Next Door (Book by Thomas J. Stanley and William D. Danko)

- The Automatic Millionaire (Book by David Bach)

- Liberate the Block, LLC

- Letters To My Sisters & Brothers (Book by Nelson Zounlome)

- PF for PhDs Community

- PF for PhDs: Podcast Hub

- PF for PhDs: Subscribe to Mailing List

- Nelson’s Twitter (@Nooz25)

Teaser

00:00 Nelson: I didn’t have an advisor who was seeing this work as a conflict, right? And instead, actually, seeing it as an asset and a complement to my research in a lot of ways. Because a lot of the work that I do is focused around my research, right? So using my skills and my expertise in a way to give back to communities in a different way, aside from writing articles and getting grants and things like that, which is, you know, often what we focus on in academia.

Introduction

00:32 Emily: Welcome to the Personal Finance for PhDs Podcast: A Higher Education in Personal Finance. I’m your host, Dr. Emily Roberts. This is Season 10, Episode 16, and today my guest is Dr. Nelson Zounlome, a recent PhD in counseling psychology from Indiana University and assistant professor at the University of Kentucky. Nelson started graduate school with a negative net worth, but over the six years of his PhD he increased his net worth to nearly six figures, including investments in both a Roth IRA and taxable brokerage account. Nelson practiced intentional frugality, particularly with respect to his large, fixed expenses and high-ticket purchases. However, what really moved the needle in Nelson’s finances was increasing his income, both through winning an external fellowship and starting a business. We discuss in detail how his business complements his research and became an asset during his recent hiring process. Without further ado, here’s my interview with Dr. Nelson Zounlome.

Will You Please Introduce Yourself Further?

01:42 Emily: I’m so excited to have joining me on the podcast today, Dr. Nelson Zounlome. He is a faculty member at the University of Kentucky, but he recently, just a few months ago, finished graduate school at Indiana University. And so we’re mostly going to be talking about his finances during graduate school. By the way, we’re recording this in October, 2021. So Nelson, thank you so much for joining me for the podcast. It’s a pleasure to have you! Will you please introduce yourself to the audience a little bit further?

02:07 Nelson: Yeah. So thank you so much for having me. Excited to be here and just share a little bit about you know, my journey. So I’m Nelson Zounlome, I did my undergrad and doctoral work at Indiana University where I studied, in undergrad, psychology and sociology, and then in graduate school, I studied counseling psychology. So as you mentioned, recently graduated and happy to have a job as an assistant professor.

Balance Sheet Before and After Grad School

02:32 Emily: That’s wonderful. So let’s go back to the beginning of graduate school. Can you give us an overview of your balance sheet at that time? Like what was going on with you financially?

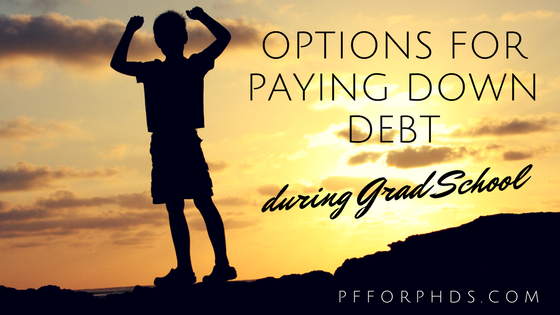

02:41 Nelson: Yeah, so when I first started graduate school, I had a stipend for my fellowship of about, I want to say, maybe $19,000 a year. So in Bloomington, Indiana, thankfully pretty affordable for the most part, so that was able to cover most expenses, but I didn’t have a lot leftover at the end of the month. Also going into graduate school, I did have $7,500 in student loans. And so one of my first priorities was to figure out basically how to get rid of that. And so that’s something that I budgeted for. During that time, I wasn’t doing an assistantship, so just focusing on classes at the time, which was helpful. So that was kind of, you know, what that looked like financially.

Assets at the Start of Grad School

03:27 Emily: So you had $7,500 of student loan debt. You mentioned your stipend, and it sounds like you didn’t have any significant assets. Did you have like a bunch of money and savings or anything like that?

03:37 Nelson: No. Maybe like a thousand or $2,000 in savings. So, you know, not a lot of money at the time, just coming right out of undergraduate. Yeah.

03:46 Emily: Yeah. So negative net worth. But having a thousand or $2,000 in the bank starting graduate school is not bad at all. And then I want to fast forward us to, when you finished graduate school, give us that picture. And then we’ll talk about how you got from A to B.

Assets at the End of Grad School

03:59 Nelson: Yeah. So by the end of graduate school, let’s see, paid off my student loan debt pretty early in my graduate program. So graduated debt-free. At that point in time had a net worth of almost a hundred thousand dollars and had a job. So yeah, that’s about where I stand now.

04:23 Emily: Fantastic. Wow. And how many years was that? How many years were you in graduate school?

04:28 Nelson: I was in graduate school for six years.

Financial Goals and Building Net Worth in Grad School

04:30 Emily: Okay. Wow. What a huge swing. I’m excited to learn more about this. So you mentioned paying off the student loan debt and you mentioned, well, you mentioned that you ended up building up significantly other assets. Did you set any particular financial goals during graduate school? Aside from the student loan debt, which you mentioned, were you intentionally building up these assets on the other side of the balance sheet?

04:52 Nelson: Yeah. So, you know, paying off the debt was my first, right. So that’s something that I budgeted for. Other things were more in line with making sure that I was living within my means, and actually below my means as much as I could and still, you know, have a fulfilling life during graduate school. So things like keeping track of all my expenses throughout graduate school. But also, you know, keeping costs low with things like furniture. So, you know, getting secondhand furniture in graduate school and on college campuses, there are a lot of ways to get free or reduced furniture. I think, you know, a lot of students don’t realize that you know, and that was a huge way. And then also just rent. So something that I was willing to do was actually move regularly to find a better living situation, particularly if that meant a better cost or just, you know, closer to campus. So then the commute time and commute costs were down. So those were the things that I kind of considered. And then thrifting, right? So just, you know, anytime I needed something new, I would check multiple locations for that to make sure that I got a good deal to keep costs low.

05:59 Emily: Yeah, those are some great frugality tactics. I guess what I’m asking is, did you accidentally build up a net worth of a hundred thousand dollars? Or like, were you like no, I’m funding my IRA and like I’m also have these savings goals or like what was going on in your mind with respect to, you know, what were you pursuing and also, why were you pursuing it?

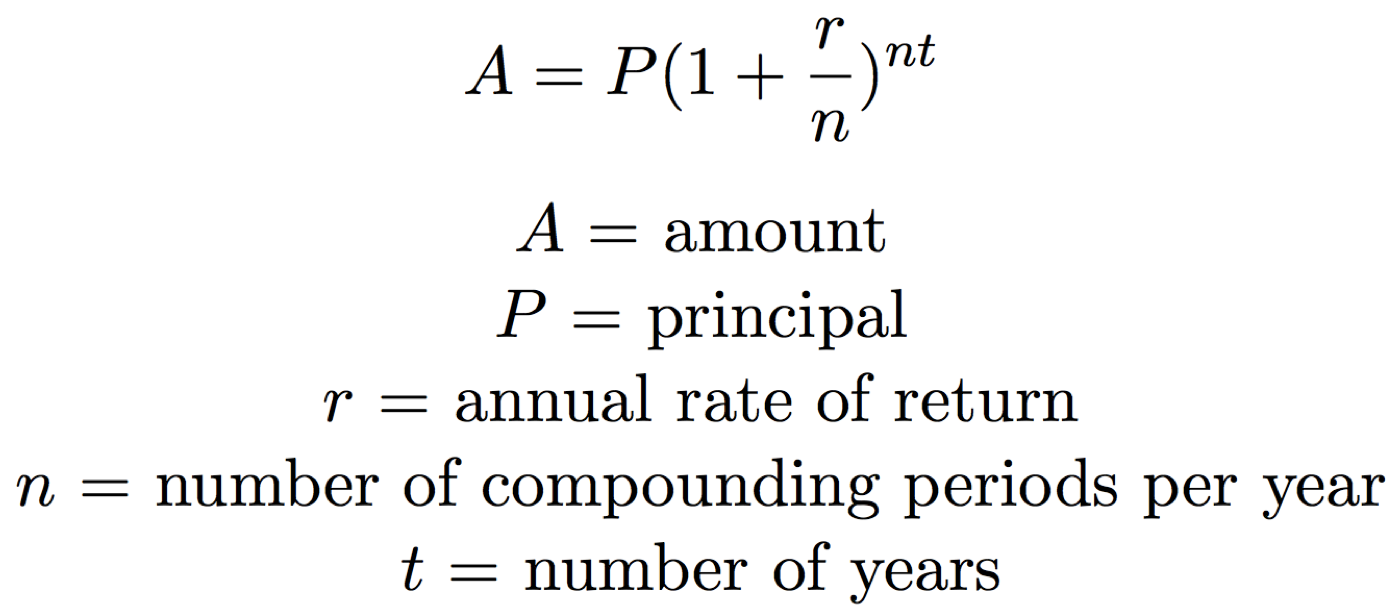

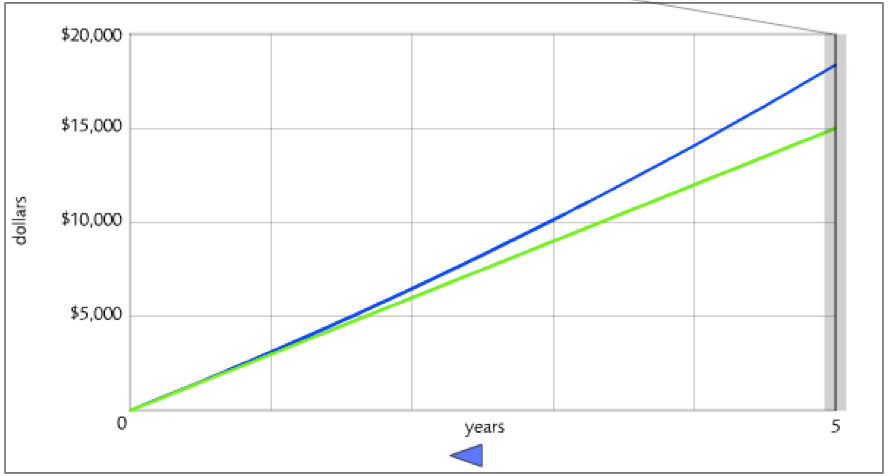

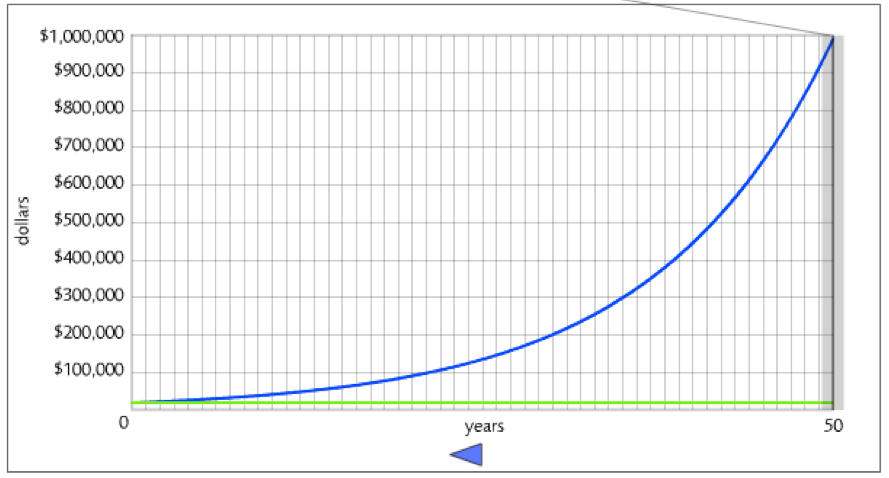

06:18 Nelson: Yeah, yeah, yeah. So it was part accident, and in part planned. So I would say initially, right, the debt was the biggest thing, but once I had that figured out, it was like, okay, I got used to living, you know, with this take-home., right? And so the idea for me was, okay, I should save this money because I’m going to need it for other things. And so that’s initially all it was, was saving. And then it was maybe my third or fourth year, I kind of stumbled upon different podcasts, different books, right? So, you know, Millionaire Next Door, Automatic Millionaire, you know, other kinds of resources like that, that got me more knowledge around Roth and retirement and brokerage accounts and things like that. And so I spent a lot of time over the next couple of years researching that.

07:06 Nelson: You know, listening to your podcast and other things like that to figure out like, oh, there’s much more that I can do with my money beyond just saving it, right? And so the motivation behind you know, a lot of that too, is that I grew up poor, right? So I grew up from in a very low-income, single-parent household. I lived in public housing for most of my life. And so you know, a lot of the messages I received about money were just save, save, save, right? And so it wasn’t until I got to these other resources that I realized that I can invest it, right? I can do other things. And then in addition to that, so that’s kind of the part that I stumbled upon, right? But the more intentionality came with learning, and then another really big strategy that I think is important for graduate students to know is being able to monetize your skills. And so something else that I did was create a business, right? And so I created my business, which is Liberate the Block, which is focused on providing educational and mental health resources for BIPOC students to help them live their lives holistically. And so I was able to create and publish a book. I was able to create an online course specifically for those groups of students, which help also contribute to my net worth and things like that.

Paying Off Student Loan

08:23 Emily: I’m really glad you brought that up. And we’re going to go more into detail about that in a moment, but like doing the quick math for me, I’m thinking $20K stipend times six years, $120,000. How did you get, you know, almost a hundred percent like savings rate on that income that you’re making? But it’s because we went beyond the stipend to make more money. So that’s great. So we’ll talk about that more in a moment. Since it was the student loan debt repayment that kind of kicked off this whole process for you, why did you decide to repay that student loan? Did you have to, or could have been in deferment? What were your decisions around that?

08:59 Nelson: I did not have to, it could have been in deferment, but it was something that it was instilled in me long ago that that debt is just something in my family that we don’t like. And so, you know, even that by comparison to others that I know is a small amount of debt. It’s just something that I didn’t want hanging over me, something I didn’t want to have to deal with later. And so it was just something important for me to feel financially secure and to really start that, getting rid of that debt and then focusing on how I can grow that net worth afterwards.

09:32 Emily: I’m so glad you brought that up because, are you familiar with like the debt snowball and the debt avalanche methods?

09:37 Nelson: I am. Yeah. And it was kind of unintentional that I did that. Yeah.

09:41 Emily: Well, what I like about this is that like, according to the debt avalanche, and also according to what I like typically teach, defer those student loans, pay them off later, especially if they’re subsidized. But what I like about what you said is that it was important to your psychology to get rid of that debt. And that’s much more in the debt like snowball camp of like get rid of these small debts. Like you don’t even want them on your mind. And of course, I mean, $7,500 is a small amount of money, but compared to your stipend, that’s like over a third of your stipend. So in your world, it was not a small amount of money, but anyway, so I’m really glad to know like your reasoning for why you did that. And I totally, if it helps you sleep better at night, like that’s awesome. Go for that.

Increasing Stipend and Income in Grad School

10:20 Emily: So let’s talk more about increasing your income and let’s start, like, in your role as a graduate student, was there anything you did to increase your stipend over the course of graduate school?

10:31 Nelson: Yeah, so something that I did as well was looking for an increase in stipend through a fellowship. So I was able to apply for, and luckily received my second time around, a national fellowship that increased my stipend from the 19 to about $24,000 a year. And so, you know, me being me, I kept my cost of living the same, right? So even though I had a higher stipend, I was being able to use that in the same way for my expenses. So that is also kind of what helped me, you know, start to increase my net worth and then start to use some of that money to invest in a general sense, right? Brokerage account, Roth, and things like that. But then also back into myself through things like my business and other things.

11:20 Emily: Gotcha. And I believe what I heard you say is that you started off graduate school with a fellowship as well, right? Not an assistantship. And then you got this higher fellowship later on.

11:31 Nelson: Correct.

11:31 Emily: So you didn’t have like teaching responsibilities or any research responsibilities that didn’t relate to your dissertation, is that correct?

11:40 Nelson: Well, so my first year, I did not have any of those responsibilities, but then my second and third year I did teach. And then my fourth year on, because I got that additional fellowship, I did not have those responsibilities. But as a counseling psychologist, I was also engaged in clinical work, you know, 10 to 20 hours a week on top of classes and teaching and things like that. So that took up a good amount of my time as well.

Business Helped Increase Net Worth

12:06 Emily: Wow. Okay. Busy schedule, because now we’re about to add the business in here as well. So you mentioned the name of it and a little bit of the mission earlier, but let’s talk more kind of like tactically, like what was bringing in money for you during that period of time?

12:22 Nelson: Yeah. So what was bringing in money were, you know, book sales, right? So, the book that I published which is you know, a book for BIPOC students to help them thrive in undergrad and graduate school. So that was actually the primary way. But then also I started being able to do speaking gigs. I also worked as a consultant, right? So individually with students to help them thrive in graduate school and undergrad, but then also working with, you know, larger school programs that focused on student success or, you know, BIPOC students matriculating into graduate school and things like that. So that’s also, you know, work that I’ve continued to do and to be hired for. And so that’s, you know, definitely increased my net worth in a good amount.

Finding Mentor Support and Being a Mentor

13:09 Emily: I love your story, because it’s been rare to have on the podcast, like a true business owner who started that business during graduate school and made significant income from it. Because this is also bringing up questions for me around like, your advisor must have known about this because you’re being invited to speak places and so forth. Like, and then, so how did you handle those conversations about sort of balancing your world as a graduate student and your role, like launching this business? And then there’s a time management portion of it too. So can you give us a few comments about that?

13:41 Nelson: Yeah. I mean, luckily my advisor, super great you know, very, very just, just a great mentor, really, not else to say about that, but he was really supportive. And so, you know, when he was found out that I was writing the book and then I published the book, right? He was one of the first people to get it and he was excited about it and encouraged me to do speaking and other things like that. So, you know, I assume that really helped me as well. I didn’t have an advisor who was seeing this work as a conflict, right? And instead, actually seeing it as an asset and a complement to my research in a lot of ways because a lot of the work that I do is focused around my research, right? So using my skills and my expertise in a way to give back to communities in a different way, aside from writing articles and getting grants and things like that, which is, you know, often what we focus on in academia.

14:35 Emily: It actually sounds to me like, I don’t know how this is in your field, but it sounds to me like you were doing as a graduate student, the kinds of things that faculty members do. The kinds of, you know it’s not even really a side hustle, it’s part of their work. It’s just not part of their job, right? As a faculty member, they publish books, they do speak, and they do all these other things, yet seeing that at the graduate student level is uncommon. Can you say, like, how did you like get up the like, audacity, like do this to like launch this huge thing, like as a graduate student? Like, how did you have the idea that this is even going to be possible during this time?

Monetize Your Skills

15:13 Nelson: Yeah. So in those same books you know, that I had mentioned, or just resources that I was consuming at the time around finance and retirement and all those things, something that kept coming up was, if you want to increase your net worth, you know, one of the best ways is to monetize your skills, which is to create a business, right? And so, you know, I was working on a research project that had to do with advice for students of color, which is, you know, what ended up becoming my book. But when I was doing that, I was like, man, this is really great advice that these participants are giving. It would be great to be able to put this in a medium, other than a research article, right? And so that’s where the idea of a book came. And then from there, it was just doing a lot of research around how to start the business, right?

15:58 Nelson: How to start, you know, doing all of these pieces. But because it was, you know, something really similar to the work I was already doing and because I am genuinely passionate about and excited about helping BIPOC communities and students in general, to me, it just seemed like a natural fit and complement to the work I was already doing. And so, you know, the time management piece was difficult, right? You know, staying up late and working hard and doing this and doing that. But, you know, I feel like the reward of just being able to engage with students really just gives me a lot of energy and excitement around that.

16:34 Emily: Wow. I’m so excited about this journey for you. This is amazing. I don’t know if this is like reading too much into the situation, but it sounds like these personal finance and entrepreneurship related books that you were reading maybe opened your mind to that possibility more so than maybe the average graduate student would be. And okay, so I think I also had kind of a similar experience from books and also from other types of personal finance content to like, think about, oh, wow. Like I can invest while I’m a graduate student. I don’t have to be limited to this like student mindset. There’s things I could do in my finances beyond this. For me, it didn’t look like starting a business at that time. But doing other things for my finances that were like pretty ambitious, like for a graduate student. It sounds like you went through a similar journey as well through this reading and exploration.

17:25 Nelson: Yeah. One hundred percent. And something that, you know, I often recommend to students as well is, you know, really take ownership of your education. Yes. But also remember that universities are really big resources, right? And once you leave, you know, academia, we often lose access to those resources. So while you’re there, it’s really, really important to take stock of that. And so something that, you know, I definitely should mention is at my university at IU, we have so many resources like access to lawyers, access to people who will help you with business planning, access to people who will talk to you about finances and other things like that. And so that was part of what I did was just take stock of the resources that already existed at my university and use all of those things to my benefit, to help launch my business. And so that’s something I would 100% encourage students to do is to take a stock at what the resources are at your university. And think about how you might be able to take advantage of some of those in a similar way.

18:28 Emily: Love that message. Wish I had heard that during graduate school!

Commercial

18:33 Emily: Emily here for a brief interlude. If you are a fan of this podcast, I invite you to check out the Personal Finance for PhDs Community at PFforPhDs.community. The Community is for PhDs and people pursuing PhDs who want to take charge of their personal finances by opening and funding an IRA, starting to budget, aggressively paying off debt, financially navigating a life or career transition, maximizing the income from a side hustle, preparing an accurate tax return, and much more. Inside the community, you’ll have access to a library of financial education products, including my recent set of Wealthy PhD Workshops. There is also a discussion forum, monthly live calls with me, and progress journaling for financial goals. Our next live discussion and Q&A call is on Wednesday, December 15th, 2021. Basically, the community exists to help you reach your financial goals, whatever they are. Go to pfforphds.community to find out more. I can’t wait to help propel you to financial success! Now back to the interview.

Liberate the Block is an Asset

19:45 Emily: With respect to your business, how much of a role did that play in your hiring process? Like, was it an asset that you have this business on the side?

19:56 Nelson: It was, and so, you know, as a counseling psychologist, one of our core components is social justice and multiculturalism. And so since my research and my business, you know, that’s basically the heart of those things as well. It was something that actually came up, you know, during my interview process. But it was referred to as an asset like Oh, you know, I was also a published author of a book, right? Not just on articles and you know, those types of things.

20:23 Emily: Fantastic! Is there anything you want to say further about either your business or increasing your income during graduate school?

20:31 Nelson: You know, if anyone wants to find more out just about the business itself, you can go to liberate the block dot com. And again, focusing on just the mental wellness and academic persistence of BIPOC students and professionals. And so book, out there already, and then an online course as well. So check that out if that’s useful.

Limiting Home Expenses

20:53 Emily: Fantastic. Let’s turn our attention to the other half of the cashflow equation, your expenses during graduate school. You mentioned earlier a couple of the strategies that you used to decrease your expenses. For example, I want to hear a little bit more about moving, because I kind of always point to these, like, you know, your big fixed expenses, housing being the top one on that list as targets for, if you’re trying to reduce your expenses, you need to think really critically about that particular line item. So can you tell us a little bit more about why you chose to move and how you made it work?

21:26 Nelson: Yeah, so because I had done my graduate school in the same place that I did my undergrad, or I guess we could flip those. You know, I was pretty familiar with the town already at Bloomington. And so I initially, you know, just wanted to switch the side of town that I lived on. So, I lived on one side of town, and I enjoyed it, but you know, it wasn’t the best, right? And so when I was able to find something that was closer to campus that was actually a bit more affordable, you know even though I hate moving, I was like, okay, this financially makes sense. And so and then also I was at the same apartment complex and I actually ended up moving right just across the street to another apartment for kind of a similar reason in the same complex. And so basically, you know, I was just able and willing to make that transition, you know, in light of my fixed cost of always thinking about, okay, how can I keep costs down?

22:28 Emily: That makes sense. And with a market like Bloomington, I have to ask, you chose to rent. Was buying ever on your mind as a possibility?

22:38 Nelson: It wasn’t until I had been there for quite some time, so maybe, you know, in the same time where I was consuming all of these finance, you know mediums, right? It was like, oh, buying actually maybe would have made a lot of sense. But around that time, you know, I only had about a year left in the program. And so it just didn’t make sense to me because I also had no idea where I was going to be in the next year. And so it was something that I definitely wish I at least would have looked into early in their process. And had I known, I would have continued on into graduate school a little bit earlier in Bloomington, that definitely would have been something that would have made a lot of sense. Because over the course of that time, I was in Bloomington for nine years. My last year, my program was an internship. I actually lived in Baltimore, Maryland. But for nine years I was in Bloomington. So yes, that would have been awesome to have been paying all that money for a house and not just for rent.

23:33 Emily: I do think it probably would have been difficult though, like on your $20K like starting stipend. I don’t know how well, you know, we have to go back in the Wayback machine to figure out housing prices at that time. But it may have been too much of a stretch. But by the time your income increased, like you said, your time is growing short in that particular city, so totally understand why it went that way. Are there any other areas of spending that you want to bring up where you like intentionally tried to sort of keep a lid on expenses?

Keeping a Lid on Expenses

24:02 Nelson: I mean, this kind of goes along with furniture, but just honestly anything that was kind of a high ticket item, right? So even when I got a new monitor for my computer, even when I got a desktop, just so I could work at home with and things like that a bit better. We have a surplus store at IU called the IU surplus store. And, you know, they would have old monitors, old desktops, old furniture, old, you know, whatever there. And so, you know, anything that was high ticket, I would almost always go there first to see if they had it to keep those costs down. You know, something I was also mindful of is, you know, food budget, right? So not eating out very often or limiting myself to about you know, just a couple of times a month. And just being mindful of that. And then just doing my best to, if there were conferences or other things, looking for funding for that. So within my program at the national level for my professional organization, I was constantly applying for these grants, fellowships, travel awards and things like that. So that spending, you know, to conferences and whatnot didn’t have to always come out of my pocket. And so I think I was able to really save a lot of money that way, compared to some of my peers.

25:21 Emily: I think this, it sounds like so strategic now, like you were focusing on building, of course, graduating, also building your business, increasing your income focusing on the big line item of housing, and then just letting you know, it sounds like you’re a naturally like frugal person, but just not being too concerned about the minutia. But just when those, as you said, the higher ticket items came up, made sure that you were being really intentional about your spending in those areas. And so in that way, your energy kind of goes more towards this like increasing income side of the balance sheet. I know for me in graduate school, I probably went more to the frugal, like extreme than was necessary and probably put too much energy over there. I should have been focusing more on like the increasing income or, you know, preparing for the next job, like side of the spectrum, but it’s all in retrospect.

Current Money Mindset

26:06 Emily: Okay. So you talked about how, you know, during this six years in graduate school, your net worth went from slightly negative to almost a hundred thousand dollars. Wow. Amazing. How has that set you up financially for your current like career stage and life at the University of Kentucky?

26:23 Nelson: Yeah. So I would say, you know, for me, I’m really using the same principles, right? So you know, I have a pretty cheap place. You know, two bedroom, but my rent is below a thousand dollars, which is great. But you know just based on the cost of living and everything here, I definitely be paying more to live in a more expensive area, right? Maybe with some more amenities and things like that. But it’s important for me to you know, spend my money on my business and other things that are a bit more important to me like visiting family. So I’m happy that I live pretty close to family, and less around kind of the rent side. And now I’m actually choosing to rent as opposed to buy, because I want to get a sense of the area right now before, you know, buying a house.

27:10 Nelson: And also as I’m sure you’re aware of like this whole past few months for buying was ridiculous. So as a first time home buyer, I was like no, I’m okay. But yeah, so just really keeping the same cost of living, like the same habits, the same cost of living for myself into my profession that I was as a graduate student. So, even though, you know, my salary is much higher than my stipend was, I didn’t then magically start, you know, spending a lot more. I’m keeping the same habits because I was pretty comfortable, right? I spend more money on higher price items that, you know, I think are good investments for long-term and things like that. But, you know, my eating habits haven’t changed much, right? The way that I obtain furniture is actually very similar, right? My budget on that has increased a bit, but you know, I’m on Facebook marketplace, I’m looking around, you know, here, I’m going to Goodwill, I’m going there, you know, just to see what’s around. So, you know, it’s important for me to keep those costs down so I can save more, invest more, and also just have more, yeah.

Investments and Retirement

28:12 Emily: Tell me what you’re doing with your investments now? Are you maxing out? What’s up?

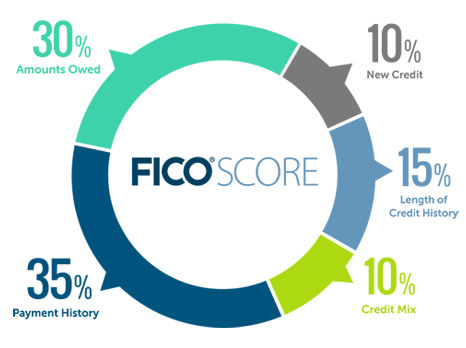

28:18 Nelson: Yeah. So right now I’m maxing out my 403(b), which has an employer match, which is amazing. And then I’m also making the max contribution to my individual Roth. And then I also am able to contribute a little bit right now to an actual, additional Roth that I have through work, which is really cool. And then I also have a brokerage account that I fund pretty regularly, too. And so all of those things are just automatic, right? So, you know, my paycheck comes, and all that money is taken from my paycheck to the different accounts invested automatically. And so I think that’s also just the beautiful part is that I really don’t miss the money because I don’t really ever see the money, right? It’s all in these other accounts. So I don’t even get the chance to spend that extra money. It’s just taken directly. And you know, it’s just invested in growing. And so once retirement hits, you know, at this point, even, I’m not actually that concerned about retirement, right? If, you know, as expected, my career continues and you know, my income hopefully will increase over time.

29:24 Emily: That’s fantastic. And I think that what you’ve done makes so much sense for someone in your situation where you have this like big, big jump in income and you don’t really feel the need to increase your lifestyle that much. Sure, a little bit here and there, on parts that are important to you. But overall not making a huge leap in lifestyle, just funneling all that money away into your investments and watching it grow. And then you’ll have lots of options in the future, right? Whether it’s retiring early or doing something fantastic with the money in another way. That’s awesome.

Best Financial Advice for Another Early-Career PhD

29:54 Emily: So let’s conclude the interview with the question that I ask all of my guests, which is what is your best financial advice for another early-career PhD? And that could be something that we touched on in the interview, or it could be something completely new.

30:08 Nelson: I feel like I have several pieces of advice, but I will keep it short. So I would say, my first thing is, I know from experience how overwhelming and how uncomfortable, and that’s a lot of what you address, you know, in some of your materials Emily, is how uncomfortable that can be at first, especially when you come from a background that money wasn’t something that you really talked about and whatnot. But really, you know, utilize these resources such as this podcast and, you know, other books and materials to just learn. And once you get past that little bit of discomfort, it’s actually, it’s pretty easy, right? So to be able to set up, you know, these accounts into investing, and so really just believe in yourself. Yes, it’s going to be uncomfortable.

30:50 Nelson: Yes, it’s going to be anxiety-provoking, but you know, once you get past that and set yourself up, you’re really mostly set up for the rest of your life, which is great, right? And in a really short period of time, you could set yourself up for financial success, which is amazing. And I really wish I had known that my first year. I’m very happy I stumbled upon this, but I really wish I had, you know, more of a resource like this beginning, so I could have been more intentional. And then the other piece is, you know, what I touched upon before is really take stock of your university resources and see what is there for you, right? And really think about, you know, whether that be through lawyers or, you know, business incubators, or, you know, just pitch competitions, all these things that happen at universities that might be helpful for you, if you’re someone that, you know, making a business or even being a part of a business makes sense.

31:41 Nelson: And related to that is we, as PhD students, have a lot of really marketable skills. And I think, you know for those of us who are in fields that industry isn’t something that’s discussed as much as an option, I would take the time to research careers, right? Because you know, myself as a psychologist, we often think about clinical work or academia, right? But we don’t think about all the plethora of ways in which we can apply our degree, right? And so, you know, think about ways outside of those two mediums that you might be able to contribute while in graduate school or outside that might, you know just help increase your financial wellness.

32:24 Emily: So well-put, I’m so glad we’re ending the interview there. It’s wonderful advice. Thank you so much for volunteering to give this interview, Nelson. I really enjoyed talking with you, and I’m just so glad to see this bright career and financial future ahead of you. It’s wonderful.

32:38 Nelson: Yeah, thank you so much! I appreciate it.

Outtro

32:45 Emily: Listeners, thank you for joining me for this episode! pfforphds.com/podcast/ is the hub for the Personal Finance for PhDs podcast. On that page are links to all the episodes’ show notes, which include full transcripts and videos of the interviews. There is also a form to volunteer to be interviewed on the podcast. I’d love for you to check it out and get more involved! If you’ve been enjoying the podcast, here are 4 ways you can help it grow: 1. Subscribe to the podcast and rate and review it on Apple Podcasts, Stitcher, or whatever platform you use. 2. Share an episode you found particularly valuable on social media, with a email list-serv, or as a link from your website. 3. Recommend me as a speaker to your university or association. My seminars cover the personal finance topics PhDs are most interested in, like investing, debt repayment, and effective budgeting. I also license pre-recorded workshops on taxes. 4. Subscribe to my mailing list at PFforPhDs.com/subscribe/. Through that list, you’ll keep up with all the new content and special opportunities for Personal Finance for PhDs. See you in the next episode, and remember: You don’t have to have a PhD to succeed with personal finance… but it helps! The music is “Stages of Awakening” by Podington Bear from the Free Music Archive and is shared under CC by NC. Podcast editing by Lourdes Bobbio and show notes creation by Meryem Ok.