In this episode, Emily interviews Dr. Jamie Lahvic about her experience being funded by fellowship during grad school at Harvard and her postdoc at the University of California, Berkeley. Regarding the tax complications of being on fellowship and the lack of retirement benefits, Jamie and Emily outline the issues, discuss possible solutions, and suggest advocacy avenues for instigating change. Listen through the end of the interview for the Big Questions regarding the true nature of fellowships and employment.

Links Mentioned in the Episode

- PF for PhDs: Set Yourself Up for Financial Success in Graduate School (Workshop)

- PF for PhDs S14E3 Show Notes

- PF for PhDs Episodes on Fellowship Income Tax

- S2 Bonus Episode 1: Do I Owe Income Tax on My Fellowship? (Expert Discourse with Dr. Emily Roberts)

- S6E9: How This Grad Student Fellow Invests for Retirement and Pays Quarterly Estimated Tax (Money Story with Lucia Capano)

- S12E6: How Fellowship Recipients Can Prevent Large, Unexpected Tax Bills (Expert Discourse with Dr. Emily Roberts)

- S14E1: Five Ways the Tax Code Disadvantages Fellowship Income (Expert Discourse with Dr. Emily Roberts)

- S14E2: How This Grad Student Fellow Resolved an Expensive Tax Bill in His Favor (Money Story with Matty Dowd)

- PF for PhDs Quarterly Estimated Tax Workshop

- FreeTaxUSA

- PF for PhDs Tax Center

- PF for PhDs S4 Bonus Episode 1: Fellowship Income Is Now Eligible to Be Contributed to an IRA! (Expert Discourse with Dr. Emily Roberts)

- PF for PhDs Episodes Where Grad Students Discuss Contributing to a 403(b)

- PF for PhDs S13E2: This PhD Student-Nurse Is Confident in Her Self-Worth (Money Story with Brenda Olmos)

- PF for PhDs S13E8: This First-Year PhD Student Prioritizes Investing While on Fellowship (Money Story with Michele Remer)

- Future of Research

- PF for PhDs S2E3: Using Data to Improve the Postdoc Experience (Including Salary and Benefits) (Expert Interview with Dr. Gary McDowell)

- PF for PhDs Subscribe to Mailing List (Access Advice Document)

- PF for PhDs Podcast Hub (Show Notes)

Teaser

00:00 Jamie: Because I often felt, you know, in addition to like the confusion and the frustration and wondering what to do, that I don’t know, it felt like an emotional hit. I felt unvalued when I’m put into this weird little category where my earnings don’t make sense and I can’t open an account and I can’t figure out how to pay taxes. And I went on this really kind of rollercoaster from feeling like, “Oh, I’m a valued scientist and worker in this field,” down to like, “Oh, nobody really cares about me or the type of work that I’m doing.”

Introduction

00:38 Emily: Welcome to the Personal Finance for PhDs Podcast: A Higher Education in Personal Finance. I’m your host, Dr. Emily Roberts, a financial educator specializing in early-career PhDs and founder of Personal Finance for PhDs. This podcast is for PhDs and PhDs-to-be who want to explore the hidden curriculum of finances to learn the best practices for money management, career advancement, and advocacy for yourself and others. This is Season 14, Episode 3, and today my guest is Dr. Jamie Lahvic. We discuss Jamie’s experience being funded by fellowship during grad school at Harvard and her postdoc at the University of California, Berkeley. Regarding the tax complications of being on fellowship and the lack of retirement benefits, Jamie and I outline the issues, discuss possible solutions, and suggest advocacy avenues for instigating change. Listen through the end of the interview for the Big Questions regarding the true nature of fellowships and employment.

01:43 Emily: If there are any prospective PhD students listening—and I hope there are—I want to point you to a new workshop I’ve been publishing in installments throughout this academic year, Set Yourself Up for Financial Success in Graduate School. Now that we’re in admissions season, the modules are getting really exciting and immediately actionable. The two most recent modules are titled “Decipher and Compare Your Offer Letters” and “How to Negotiate Your Stipend and/or Benefits.” One from last fall that you might want to check out as you’re evaluating the cities your offers are in is “Stipends vs. Cost of Living.” I sincerely want you to go into grad school with your eyes wide open regarding the financial realities and in the strongest financial position possible for the program you choose. I hope you will check out the workshop and enroll in the modules that will help you accomplish that. Go to pfforphds.com/setyourselfup/ for more information. You can find the show notes for this episode at PFforPhDs.com/s14e3/. Without further ado, here’s my interview with Dr. Jamie Lahvic.

Will You Please Introduce Yourself Further?

03:01 Emily: I have joining me on the podcast today, Dr. Jamie Lahvic. Super delighted to have Jamie here. We actually met at a conference last summer. I’m recording this in November, 2022. So, we met at the Graduate Career Consortium Annual Meeting, which was in July, 2022. We ran into each other during like a break or something, and we just started chatting and we had this electric conversation about funding, about fellowships, about benefits, about systemic issues that need to be addressed. And I just wanted to capture some of that magical conversation here on the podcast. So, Jamie, I’m super delighted to have you on. Will you please introduce yourself to the audience?

03:42 Jamie: Sure! My name is Jamie Lahvic. I am currently working as a Program Officer at the National Institute on Aging, where I focus on some policies as well as programs related to graduate students, postdocs, and early career faculty. But today I’m kind of excited to talk about my own personal experiences as a graduate student and then a postdoc. So, I went to grad school at Harvard Medical School studying biomedical sciences and then I moved on to UC Berkeley to do a postdoc in cancer biology. And I wrapped up that postdoc in 2021.

04:18 Emily: I’m really excited to see all these different perspectives from you being at a private university, a public university, now in government. Like, this is awesome! And I’m of course going to share some of my own limited experience as well. But we’ve both had some observations about these issues about the finances and the benefits and so forth that are offered to graduate students and postdocs as employees or as fellows. So, I want to, for the listeners just to introduce them. I have a framework, this is not necessarily the way that everybody talks about this, but in my mind there are sort of two broad classifications that graduate students and postdocs can fall into. One is as an employee. The way you know that you’re an employee especially if you’re a citizen or resident, is if you receive a W-2 <laugh> at tax time, that’s like really indicative that you’re an employee.

05:04 Emily: So, you have this employer/employee relationship with the university and that may cause different benefits and so forth to be offered to you. The other classification, a little harder to name, a lot of people use the term fellowship, but not only things called fellowships could fall into this classification. So, I broadly call it awarded income when your income comes from an award that you received. Could be certain types of grants, could be a fellowship, could be some other things. So, that’s the language we’ll be using. We’ll just say fellowship for shorthand, but that basically just means non-employee or at least under the, you know, the timing and circumstances of receiving that award, you’re a non-employee.

Switching Between Grad Student Funding Sources

05:37 Emily: Okay. With that clarification out of the way, let’s talk about, you know, your personal experiences, my personal experiences with being an employee and/or being a fellow during grad school and postdoc. So, we’ll probably take this like topically. What would you like to share? What you know surprised you about maybe switching between these two types of funding? What issues did they bring up? Go ahead.

05:59 Jamie: Sure. Yeah, so as a graduate student, I was never an employee. I was always either paid a student stipend coming straight from the university or then a fellowship stipend once I got an NIH fellowship. So there, it still was a really complicated process. I remember being very surprised first year as a graduate student to try to figure out how to pay taxes, how to pay estimated taxes every year. And it seemed to become more complicated every year, especially because once I got my fellowship, some of my money would come from the fellowship, some of it would come from the university. Those would come in separate paychecks. And then later on once I was teaching I would get a third paycheck to cover the teaching that I was doing. And throughout all of that, I never received a W-2. Every now and then I would receive a 1099 for the teaching, but they were kind of inconsistent in whether they would send that. So come tax time, I kind of never knew what I should even do. So, that was a big struggle.

07:01 Emily: Yeah. Let’s talk about the tax issue for a minute longer, because I mean, you probably know this is like part of the bread and butter of my business now because so many graduate students and postdocs are running into confusion around the tax issues. And basically, I mean we will link in the show notes some episodes I’ve done on this in the past, but it basically boils down to like when you’re an employee, your employer has certain responsibilities in terms of telling you how much money you’ve been paid and how much money they withheld on your behalf and so forth. And once you get into this weird non-employee status, they simply don’t have those legal responsibilities in the way that they do for employees. And so, universities take like all these different approaches. And you’re saying even within Harvard, different pools of money were being reported in different ways.

07:46 Emily: And so, yeah, of course, that gets confusing for the recipient when the vast majority of our like, I mean already the U.S. tax system is so complicated to navigate, but if you step outside of the simple like employee world, it gets even harder to find, you know, the support and the resources that you need. That’s part of why I do what I do. But yeah, tell me a little bit more about how you dealt with these like challenges or complications of not having income tax withheld, for example, or like the reporting inconsistencies?

Team Effort for Taxes

08:15 Jamie: Yeah, I think a lot of the students kind of banded together to help each other. I remember we had one really proactive student who would post in our year’s Facebook group four times a year saying, “Remember, pay your estimated taxes.” And I was like so grateful to get that reminder because I was so caught up in, you know, rotations and qualifying exams and whatnot. I just couldn’t think about remembering to do this. So, just having somebody send a reminder was amazing. And then we did a lot of talking to each other to try to fill out the forms correctly. I think I was a few years into graduate school when I found your website and some of your tips, and I remember that being just amazing and just feeling like that’s something that was, you know, it’s complicated but once it’s laid out it is relatively simple. It is the type of information that the university could have given us that they never really did because they wanted to stay away from giving tax advice and they’re not a certified public accountant, and that type of thing. So, it felt like the students were on our own to try and figure it out.

09:17 Emily: Yeah, I think that again, while the universities don’t have again this legal requirement to issue tax forms that make sense, or whatever, I do think it’s really helpful when they try to address this as much as they’re able to. And I mean, I hear a lot of pushback when I work with uni–not a lot. Some places I hear pushback like, “Oh we really can’t, you know, give tax advice and so forth.” And I try to kind of make the point like, “Well, you on your own or me, like we could talk about this without it being advice.” Like we can just talk generally about how estimated tax works and what these different reporting things that are going on are. And that’s what I do like with my quarterly estimated tax workshop. Again, we’ll link it in the show notes. And so, a lot of times universities contract with me to provide that because they feel like that shifts some liability off of them and onto me and they’re more comfortable with that.

10:07 Emily: But again, just giving a little bit of education and some reminders and tips and so forth is not, to me, giving advice, because really it is ultimately up to the individual to figure this out. Like I’m not sitting down with anyone filling out their forms, like they’re still doing that on their own. I’m just providing guidance on how to do so. So, I guess this is kind of turning into an ad but like if the listener <laugh>, if you listeners are on fellowship and you want your university to help you, tell them about what I offer, because they may feel more comfortable working with me then doing this, you know, with an internal employee who, you know, might expose them to some liability.

Added Hardship of Inconsistent Tax Reporting

10:41 Emily: Okay. Estimated tax and reporting stuff, all a difficulty of being on fellowship. Anything more you’d like to add about that? Or should we move on to a new talking point?

10:52 Jamie: I just thought it, you know, in addition to kind of the confusion, it can sometimes cause real hardship. Like for me for instance, I didn’t receive a 1099 for my final chunk of teaching that I did in my like final year as a graduate student. And so, in between doing that teaching and like the spring and into summer semester, I got a postdoc. I moved across the country, I had started a whole new tax, you know, qualification as an employee there. And then when it came time to do taxes, I honestly completely forgot about the money I had gotten paid in the previous spring. Because I never received any kind of 1099, any kind of documentation, and I just didn’t pay taxes on it. And I think I like woke up in the middle of the night sometime like three months later and went like, “Oh my god, I made like thousands of dollars <laugh> that I didn’t pay any taxes on.” And then like on my own, I had to then figure out how to adjust my taxes. I had to pay a penalty for the amount that I, you know, had failed to pay previously. And at the time, like I had just spent all of this money to move cross country. I was making a postdoc salary. Like I really didn’t need to be paying any extra penalties on my taxes for that type of thing.

Potential Changes at the University Level

12:04 Emily: Absolutely. I mean, good for you for doing the amended return and everything, because I know some people will just kind of let it go after that point. But you really don’t want to let it go like multiple years and then have the IRS, I mean I know it’s rare, but it can happen that they can come after you, and then it’s an even bigger problem. So, good that you took care of it. But I think kind of what we’re saying here is just like communication, <laugh> communication is helpful around this topic. So, we’ve talked about this problem, various problems related to taxes. What are some things that could change at the university level, state level, federal level, whatever it is, to alleviate these problems?

12:41 Jamie: I mean at the university level, my understanding is that even if you’re not an employee, the university can still give you a 1099 for the money that you’ve made, and that universities, as far as I know, kind of choose whether or not to go through that step and send out those 1099s. So, I think that’s a major thing that just having a very clear document makes filing your taxes easier. You know, that’s something that like TurboTax and similar basic tax filing software knows how to work with. So, I think that would make a huge difference for a lot of students.

13:12 Emily: So, I actually did experience this during graduate school, so I’ve had a couple periods of my life where I was on fellowship. But when I was at Duke, Duke actually did manage to withhold income tax on behalf of at least me. I don’t know if every type of fellowship it was available, but at least for me, about half my years I was on this like non-employee kind of income. So, they were able to withhold on my behalf, and they did issue a 1099-MISC (Miscellaneous) at year’s end. So, that helps with like the problem you just identified of like, you know, a year and a half goes by and you’ve forgotten about some chunk of your income. Yes, that does help with that problem. The issue that it causes <laugh> is that the 1099 is most widely recognized as a self-employment income kind of document.

13:59 Emily: And so, then there’s, I feel like there’s even more burden on the recipient to properly communicate what this is with their tax software or their tax preparer. So, if they know to do that and they know that they’re not supposed to pay self-employment tax on this income, then it can work out. As a reporting document, it’s okay, but I would say, you know, nine times out of 10, people don’t know that it’s not self-employment income or maybe they know that, but they don’t know how to communicate that. And they don’t check that, they don’t understand how it’s going to affect their return. Anyway, so it can cause an even bigger mess. So like, I hesitate to say that that is the best solution. I mean really to me, I would say the 1098-T is the best form that we have as of now.

Reflections on an Adjusted 1098-T and Streamlined Tax Reporting

14:50 Emily: Although I would love it if there was just an adjusted 1098-T or a different kind of form that really could fully reflect the fellowship like situation. Because again, the 1098-T, while it’s used by many universities, they’re not required to issue one if you have more of this box five grant income than you do box one, like the educational expenses and charges. So, if they would just issue it all the time, I think that would be helpful. But even going beyond that, like this is now like a federal level kind of thing. Like if there were a different form or the 1098-T itself were somehow different, that would be even more clear.

15:26 Jamie: Totally. Yeah. Yeah, and I know anecdotally, I eventually switched over from like the TurboTax software to I think FreeTaxUSA that has a great little box to check that said you know, is this income, are you like, are you a graduate student or postoc rather than an undergraduate? Because I think it’s typically with that 1098-T where they’re trying to like not take out taxes on the portion that you’ve used to cover scholarly expenses, which applies to like an undergraduate who’s receiving, you know, tuition reimbursement, but not to a graduate student. So, I could imagine at the federal level, you could create a little box like that on the 1098-T, right? To check here if this is a graduate or postdoctoral level fellowship, right? Or check here if this money is not being used to cover tuition and scholarly expenses. It would be nice.

16:20 Emily: I think this is both like maybe a reporting option at the federal level, but also it comes down to the university level and how, like which department is the one that’s like processing these paychecks. And you are, like saying how you did about your various different incomes from Harvard, that indicates to me that like maybe payroll was issuing some of this, maybe financial aid was issuing some of this. And like having these different siloed departments separated from one another communication-wise means that things are not streamlined and you get different types of forms and maybe for you, maybe you were on different pay schedules for, you know, different sources. Yeah. So, having like a single department that handles like all, you know, income for graduate students and postdocs, whether it is payroll income for employees, whether it is, you know, non-employee income, that might help. I don’t know, maybe that’ll cause other problems too, but like right now, again, the universities are not really set up to handle this in a streamlined, or at least, I don’t want to say broadly. Some universities are not set up to handle this in a streamlined manner. Maybe others have it a little more figured out. I don’t know.

17:23 Jamie: I know actually when I got paid at UC Berkeley, it was more like that. So there, I was eventually on a fellowship as well, but I received one paycheck per month. And it was kind of interesting because, you know, I would receive my lump monthly salary or stipend from the fellowship, but only a little portion of that would get taxed. So, there would be like a little tiny bit of tax taken out, and then the rest of it was untaxed. But it at least came to me on like one single paycheck where it was very clear how much tax had been withheld, and then I could run the numbers when it came time to pay the estimated taxes on the rest.

17:59 Emily: So, it sounds like you were still receiving a pay stub. Even though a portion of this is employee. Yeah, that’s perfect. I mean, I kind of always tell people who are employees like, “Okay, look at your last pay stub, even before you receive your tax forms. Look at your last pay stub.” Maybe you have to access it through your payroll system or whatever, but you can find out how much tax was withheld. But again, those pay stubs are not generated usually if you’re a non-employee. But it sounds like Berkeley has this figured out, so I’m really happy to hear that. I would, yeah, I would love to be able to come up with like, I don’t know best practices, like which universities are using the best practices. So like, Duke has something figured out over here, Berkeley has something figured out over here. Like, I don’t know, maybe there’s a way to again, promulgate these best practices among these different universities and financial whatever, backend stuff.

18:44 Jamie: Yeah, and you know, I think great groups to kind of connect to for that are unions. Within the UC system, we have a strong postdoc union. And I think they had done a lot of pushing, you know, both on how much you get paid, but also a lot of these minute policies about how you get paid. And so I wouldn’t be surprised if the more streamlined system came about because of pressure from the union. And I’d be interested to know what other, you know, grad student unions and postdoc unions are where they’re having successes.

19:13 Emily: Yeah, I’m super glad to hear that. Exactly. Like sort of giving a voice to these, well, you might not know, but the downstream effect of this like decision that you’ve made, the way you’ve set up the system is it’s causing these problems.

Commercial

19:28 Emily: Emily here for a brief interlude! Tax season is in full swing, and the best place to go for information tailored to you as a grad student, postdoc, or postbac is PFforPhDs.com/tax/. From that page I have linked to all of my tax resources, many of which I have updated for tax year 2022. On that page you will find free podcast episodes, videos, and articles on all kinds of tax topics relevant to PhDs. There are also opportunities to join the Personal Finance for PhDs mailing list to receive PDF summaries and spreadsheets that you can work with. The absolute most comprehensive and highest quality resources, however, are my asynchronous tax workshops. I’m offering four tax return preparation workshops for tax year 2022, one each for grad students who are US citizens or residents, postdocs who are U.S. citizens or residents, postbacs who are U.S. citizens or residents, and grad students and postdocs who are nonresidents. Those tax return preparation workshops are in addition to my estimated tax workshop for grad student, postdoc, and postbac fellows who are U.S. citizens or residents.

20:43 Emily: My preferred method for enrolling you in one of these workshops is to find a sponsor at your university or institute. Typically, that sponsor is a graduate school, graduate student association, postdoc office, postdoc association, or an individual school or department. I would very much appreciate you recommending one or more of these workshops to a potential sponsor. If that doesn’t work out, I do sell these workshops to individuals, but I think it’s always worth trying to get it into your hands for free or a subsidized cost. Again, you can find all of these free and paid resources, including a page you can send to a potential workshop sponsor, linked from PFforPhDs.com/tax/. Now back to the interview.

Advocacy Avenues for Grad Students and Postdocs

21:28 Emily: The last kind of question in this area, and you just mentioned one of the advocacy avenues: unions. Can you think of any other advocacy avenues that graduate students and postdocs might be able to use to make these kinds of changes that we’re talking about?

21:45 Jamie: I mean, even outside of a formal union, I’ve seen a lot of success from graduate students and postdocs just banding together and working together on these things. Whether that is kind of peer-to-peer advice and providing resources, or working together as a group to request something from your department, from your university. You know, I have so many memories of like trying to do my taxes, trying to fill in the forms, and getting like frustrated and upset and not knowing what to do. And I think like you have peers who can help you through some of those things and at least to help you feel supported.

22:25 Emily: Now, I don’t know exactly what avenue this is, but I have noticed over the years that I’ve been studying federal taxes for, you know, as in how they affect graduate students and postdocs, that there have been changes. The 1098-T has gone through actually a big remodel in the last few years. The Kiddie Tax went through a slight change with the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. So, there have been other changes that have been made that makes me realize that changes possible. Now, I don’t know what the avenue is for letting someone know, <laugh> that you want a change to happen. Maybe it’s contacting your representative or your senator or whatever. We can talk about some of the advocacy around like retirement stuff that happened a few years ago in a moment, but the change can happen. I’m just not clear exactly how you communicate, you know, this advocacy at the federal level.

23:09 Jamie: Yeah, that’s a good question. I mean, I know I’ve been on like the IRS website looking for like from their resources, like what is their advice for people in these situations. And what I found was only a few lines, right? Like not a lot of detail. So, I would love to see, you know, coming directly from the IRS some more clear advice around these types of situations. And I do know that government agencies put out things like RFIs, requests for information, and they do have various sort of feedback channels, so trying to find those for the IRS or for your state tax departments could be one way to go about it.

(No) Access to University Retirement Accounts

23:48 Emily: Okay. Future project for me. Okay, well I just alluded to retirement accounts, so let’s talk about that next. What’s been your experience with being offered or not being offered access to university retirement accounts?

24:01 Jamie: Sure. So, as a graduate student, I didn’t have any option for any kind of retirement account. And my understanding was that from legal sort of tax reporting purposes, I wasn’t able to open an official retirement account. So, in graduate school I was making like just enough money to save up a little bit and I did start buying like some mutual funds with that. And then as a postdoc, I did have a retirement account offered. However, I started out by like not really contributing very much to it at all because I was living in this really high cost-of-living area with not a lot of income. And then I actually found out as I was going through the fellowship application process that I was going to be losing that retirement contribution once I got a fellowship coming in. So then I sort of, at the last minute just before my fellowship came in, I like maxed out all my contributions as best as I could for like the last few months and tried to top it off. But then the fellowship came in and those accounts kind of sat stagnant for the rest of my postdoc. So, that was a frustrating thing to see. And it’s definitely been really nice now for a little more than a year I’ve been in, you know, a real job with very solid you know, federal government retirement accounts. So, that’s been nice to watch those finally like properly growing.

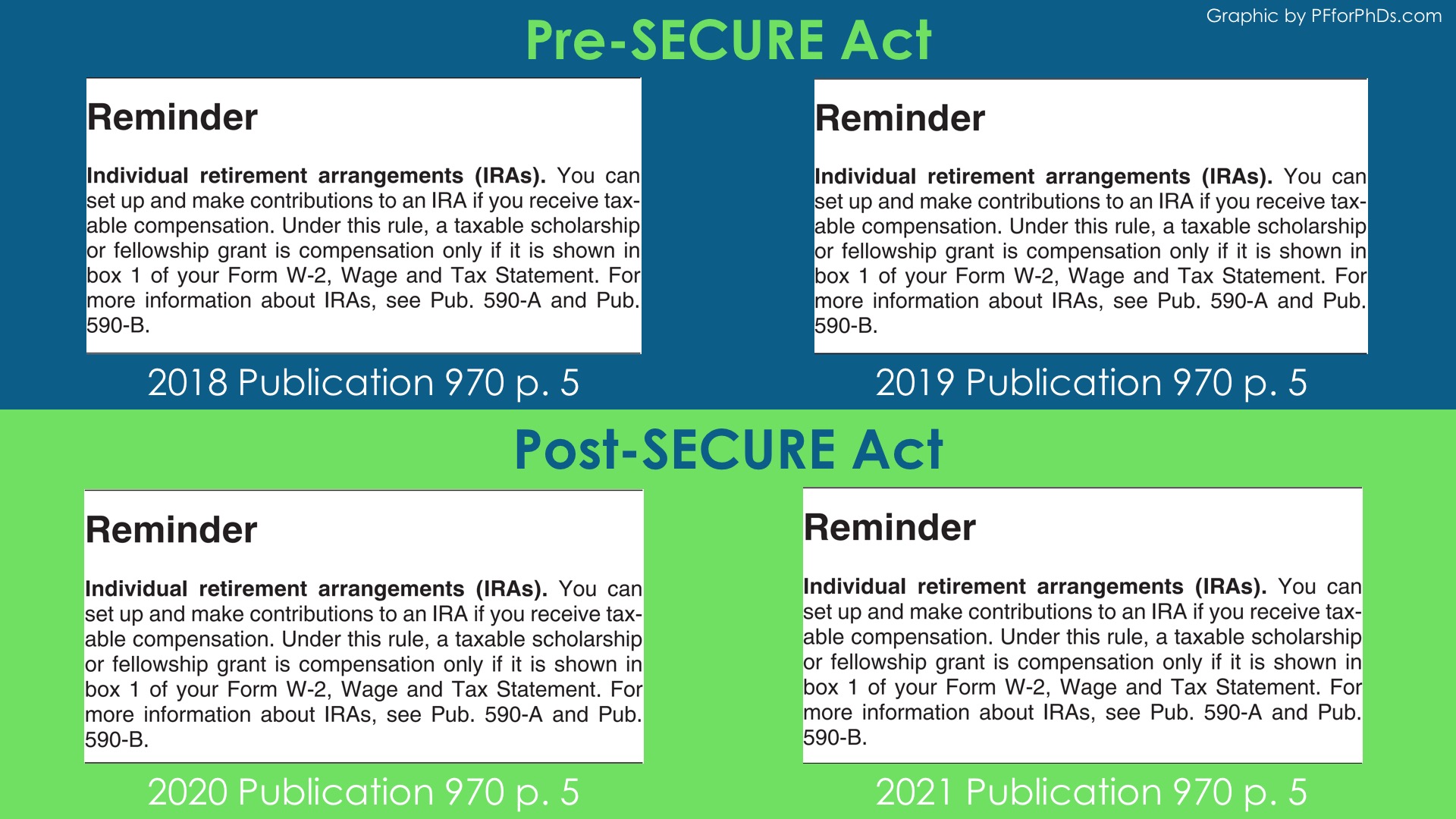

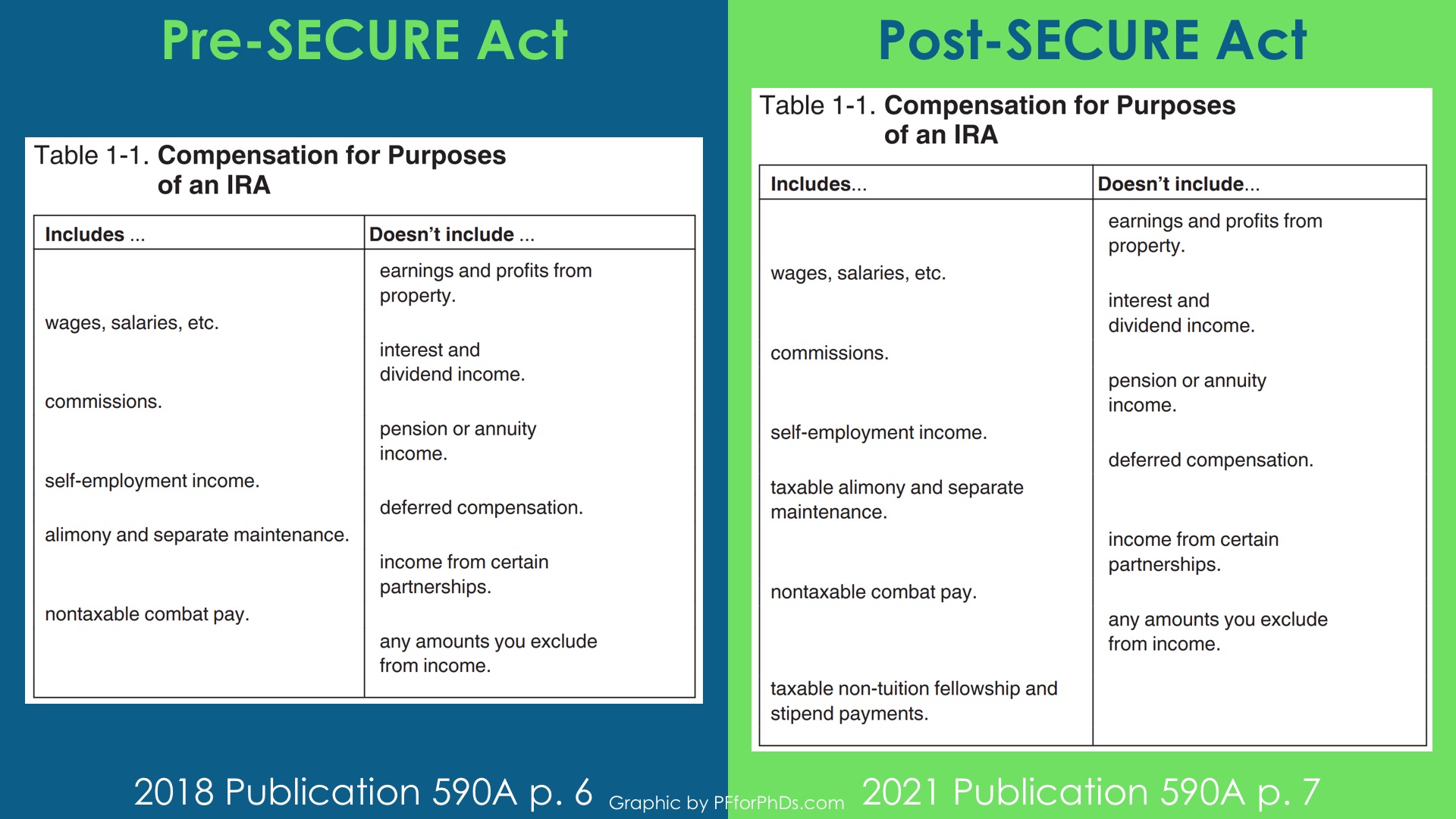

25:26 Emily: Yeah, it’s been my observation that if you’re not an employee, you do not have access to the 403(b) or 457. I actually don’t know why this is the case, but I’ve never seen an exception to it. Like yeah, I guess it has to do with like the rules behind what kinds of money can be contributed to a 401(k) or a 403(b), 457, these kinds of accounts. What I mentioned earlier, and you probably know this is, at the end of 2019 with the SECURE Act, there was a definitional change. So, 2019 and prior, fellowship-type income not reported on a W-2 was not permitted to be contributed to an IRA, an individual retirement arrangement. But that definition of what kind of money is allowed to be contributed to an IRA was changed by the SECURE Act.

26:18 Emily: And so 2020 and forward, you can contribute fellowship income not reported on a W-2, if you’re a graduate student or postdoc, to an individual retirement arrangement. I don’t know why a similar definition change could not occur for 403(b)s, 457s, et cetera. I just know that I’ve never seen it. I’ve never seen a non-employee be offered access to that particular benefit. Furthermore, at the graduate student level, it’s just very, very rare. Not totally unheard of, but rare, that a graduate student employee is offered access to those accounts. It does happen from time to time, but usually not. I’ve had a couple podcast episodes, and we’ll link in the show notes, where people have talked about as a graduate student contributing to those types of accounts. But again, it’s not common.

27:00 Jamie: I didn’t know actually about that change to the SECURE Act. Like I was still a postdoc in 2020 and I had had that IRA that I had opened like just before my fellowship started. But yeah, I definitely wasn’t contributing to it in 2020 and 2021. I had no idea that that was a possibility.

27:17 Emily: Yeah, I don’t think it was, I mean I talked about it a lot, but just like generally speaking, people make that assumption, right? That graduate students and postdocs are usually not able to contribute to a retirement account. So, why would we even have the conversation about whether they’re allowed to or not? Thankfully, someone was having the conversation because there was a change, right? Because I mean I remember that Senator Elizabeth Warren was a sponsor of this bill. There were other co-sponsors. It came up multiple times in the Senate and the House and it just never passed, multiple years, until it was rolled into the SECURE Act. There were a lot of other changes going on with how retirement accounts were being treated. So, it was kind of rolled into that and I’ll link in the show notes a couple of episodes we did right around that. But again, people make these rules. So, if people at the federal level decided that graduate student and postdoc non-employee income was legitimate in whatever, you know, little tax benefit they’re trying to offer, then it could become legitimate and maybe universities also would follow suit and start to offer that benefit. I actually don’t know why graduate students would be excluded from 403(b)s and 457s. Does it cost the university anything? Like a little more administrative burden to extend those benefits? I honestly don’t know why they wouldn’t for those students who can.

28:34 Jamie: Yeah, especially if it’s not a question of matching, if it’s just a question of contributing your own earnings into this account, right?

28:41 Emily: We can dream, Jamie, that there would ever be a match <laugh>. That’s a couple more steps down the road. No, some postdocs do receive matches or actually, I don’t know about you for being a postdoc in the UC system, but the UC system has a defined contribution level for their employees. I don’t know if it applies to postdocs, but in any case you might get that as an employee and then lose it if you, you know, then switch over to fellowship at a non-employee.

29:06 Jamie: Yeah, I believe in the UC system, I never got any kind of match, but I did have access to that 403(b) as well as I think a DCP.

29:15 Emily: Yeah.

“Non-Employee” Fellowship Income Legitimacy

29:16 Jamie: But yeah, I think it’s interesting that you describe it as like the legitimacy of being an employee and the legitimacy of that income. Because I often felt, you know, in addition to like the confusion and the frustration and wondering what to do that, I don’t know, it felt like an emotional hit. I felt unvalued when I’m put into this weird little category where my earnings don’t make sense and I can’t open an account and I can’t figure out how to pay taxes. I remember having like some really sharp juxtapositions between attending a professional conference and like giving a talk and talking to PIs in my field and having people really excited about the work that I was doing and then coming home a week or two later and trying to figure out some of my financial life and it being so confusing and seeing that there was just no support set up for it. And I went on this really kind of roller coaster from feeling like, “Oh, I’m a valued scientist and worker in this field,” down to like, “Oh, nobody really cares about me or the type of work that I’m doing.” So, I think it can have an emotional hit as well.

30:24 Emily: I’m so glad that you shared that. I think this is how we started our conversation at GCC actually, that fellowships and similar kinds of awards are supposed to be so prestigious.

30:35 Jamie: Exactly.

30:36 Emily: It’s supposed to be such an honor. It’s supposed to be based on your merit that you’ve received this. And yet the downstream effects are, well now you’ve been unclassified as an employee and your benefits are reduced. And I don’t know, maybe at some point in the past, the money made up for it. Like maybe you could make more as a fellow, which could make up for some of these issues. But I don’t know that that’s so much the case now. I was actually just seeing on Twitter today that like, you know, fellowship awards on certain grants are set at such a level that they’re below the minimums the universities have to pay their own graduate students and postdocs. So it’s like, well if you’re not even making more and the university has to make up some deficit in the award that you’re receiving, like what is the point of this when it has these negative implications later on?

31:27 Jamie: Yeah, absolutely. I mean I think the point for, well you know, it’s a point for your PI, right? It saves them some money out of their budget, and otherwise it’s a line on your resume. You got this prestigious award, congrats. Here’s some prestige. Right?

Inherent Value of a Fellowship

31:44 Emily: This almost reminds me of like, I don’t know, I’m thinking like crypto, like a currency. Like it only has value because we’ve decided it has value, it doesn’t have inherent value. If it came with more money that would be inherent value, but would it still be actually worth it? How much money would it take to make up for some of these deficits that we’re talking about?

32:04 Jamie: That’s a good question, yeah.

32:05 Emily: Right. So like, not only is it maybe the retirement stuff that we mentioned. Now on the tax front, you’re not necessarily paying more in taxes, it’s just more difficult. But I will say there are certain tax benefits I know at the federal level that you’re not eligible for if you have only this non-employee kind of income. So for example, the earned income tax credit, which is supposed to be for low-income individuals, usually with children, multiple children who are not making enough money, they have to have “earned income.” And under that definition, as of now, 2022, fellowship income is not considered earned income. So, you can’t get the earned income tax credit. You also can’t get the child and dependent care tax credit, which was so valuable in 2021. It was massively increased in 2021. You can’t get it if, let’s say even if you’re married to someone else, let’s say I ran into this situation literally I had a question from this married couple, both postdoc fellows, could not take this tax benefit because they did not have earned income under the definition. Now, graduate students can take it because students have an exception. But postdocs, everybody forgets about the postdocs!

33:08 Jamie: Everybody forgets the postdocs, it’s true!

33:11 Emily: Postdocs don’t have this exception <Laugh>. Everybody forgets that postdocs exist and yet for some, in some career paths, you can spend just as much time as a postdoc as you will as a graduate student, maybe even if not more. It’s a very important life stage. There’s family formation going on, and yet they’re excluded from some of these benefits. And like we were just saying, it comes back to is this fellowship income considered earned income? And that term earned income is used all over the tax code or the way the tax code is interpreted. Now, it used to be used for retirement account contributions, then the term was changed, taxable compensation, then the definition of taxable compensation was changed to include fellowship income. So, why can’t this term earned income be changed to include this type of income? I think this brings up a bigger, even bigger, bigger question though, which is like what is earned income?

Earned Income: Great Expectations

34:04 Emily: What is the responsibility that you have when you receive this non-employee income? What’s the responsibility that your employer has to you or your non-employer has to you? What’s the responsibility you have to your non-employer? So, if you’re an employee, you’re expected to work and produce certain outputs, whether it’s teaching, research, whatever. If you’re receiving a fellowship, it’s much less clear what the outputs are supposed to be. You have to have outputs to continue to be on the fellowship. But what are they exactly? And I think that lack of definition is what’s going into this earned income, not, you know, fellowship income not being considered earned income.

34:39 Jamie: Yeah, no, I think you’re right about that and I think that’s how this ties into kind of bigger labor questions, right? About our graduate students. Should they be classified as employees? Are they workers or are they students? And these are, you know, big things that have big implications across the U.S. and especially for universities on not just tax status but on a lot of things about how academics do their work and how academics get paid.

35:08 Emily: I’m so thankful for this conversation because it’s really like stretching me to think about these like bigger issues exactly as you were just saying. Whether we’re on fellowship or whether we’re employees, is there actually a difference there? Why are these differences encoded at the university level, at the federal level, state level, if they don’t have much meaning to us at the functional day-to-day, month-to-month, year-to-year. I know I mentioned earlier about half my time as a graduate student was spent as an employee, half as a non-employee. Functionally, what is the difference between what I was doing one year versus another year? It felt all pretty much the same to me.

35:45 Jamie: Yeah, and I think I remember it being sold to me as if you receive a fellowship, you have more independence from your PI because you’re bringing in your own money so you can be more independent in, you know, what experiments you do or how you drive your project. But in actual experience of my own or talking to other people, their level of independence was really just dependent on their PI and how that PI ran their lab. And I didn’t know anyone who was able to be more empowered because they had the fellowship or were able to push back on PI demands because of the fellowship.

36:22 Emily: I did see people who received fellowships be able to switch labs when possibly that wouldn’t have been the case otherwise. They were more attractive to that PI like accepting them. And they could, you know, take some time to get up to speed or whatever, again, without some maybe output expectations of being on a different kind of grant or whatnot. But I think you’re right, you know, we’re both kind of speaking coming from like the biological sciences kind of research. There’s so much overhead, there’s so much cost to that. How much money is the student really bringing in versus how much is their research overall costing the PI and the university? And so, if that ratio is not that great in the student’s favor, I don’t think there’s much independence that they can advocate for. Now, if your cost of doing research is like pretty much only your salary if you don’t have those kinds of overhead from doing like wet lab experiments and so forth, then maybe there’s a better argument here about independence from the PI. And I think in the humanities fields, some of them, at any rate, my understanding from talking with people is that like they have a lot more independence anyway in their research questions. And so a fellowship could be even more in that direction. But, yeah, I do think this is very, very field dependent.

37:32 Jamie: Yeah, I think that makes a lot of sense.

Future of Research

37:35 Emily: Well, this conversation has been so invigorating. Is there anything else that you want to share about your experiences or your observations or advocacy avenues that we can encourage listeners to take?

37:46 Jamie: I mean, I always love to tell people to check out the organization Future of Research. I used to serve on their board of directors and it’s a really great non-profit that kind of helps students and postdocs come together and crowdsource information and advocacy plans and push the field of research forward from the point of view of these early-career folks.

38:08 Emily: Excellent. And we will link in the show notes an interview that I did with Dr. Gary McDowell, the former director of Future of Research where we talked about post-doc salaries and post-doc work environments and how to, you know, choose a supportive PI and these kinds of questions. That’s excellent. Well, Jamie, I’m so glad that we got this interview out on the podcast that it didn’t just have to stay in the halls of the GFF conference, but that’s where great ideas are born with these like mixings and so forth and it was great to meet you in person and yeah, to be able to record this for the podcast listeners. So, thank you so much for coming on!

38:44 Jamie: Thanks, it was wonderful talking to you!

Outtro

38:51 Emily: Listeners, thank you for joining me for this episode! I have a gift for you! You know that final question I ask of all my guests regarding their best financial advice? My team has collected short summaries of all the answers ever given on the podcast into a document that is updated with each new episode release. You can gain access to it by registering for my mailing list at PFforPhDs.com/advice/. Would you like to access transcripts or videos of each episode? I link the show notes for each episode from PFforPhDs.com/podcast/. See you in the next episode, and remember: You don’t have to have a PhD to succeed with personal finance… but it helps! The music is “Stages of Awakening” by Podington Bear from the Free Music Archive and is shared under CC by NC. Podcast editing by Lourdes Bobbio and show notes creation by Meryem Ok.