Form 1098-T is issued to many (though not all) graduate students and reflects some of their higher education income and expenses. Until this year, the 1098-T was rife with problems for funded graduate students, and in many cases caused more confusion than it clarified. The 1098-T underwent a makeover in 2018, which corrected the worst of these problems. However, the shift could cause funded PhD students to owe a larger-than-expected amount of tax in 2018.

Further reading: How to Prepare Your Grad Student Tax Return

What Is Form 1098-T?

Form 1098-T is a tax form generated by educational institutions to communicate the education-related expenses and income associated with an individual student. It reflects the transactions in the student’s account (e.g., Bursar’s account) from a given tax year. The form’s primary use is to document the amount of money a student (or the student’s parents) may be able to use toward an education tax benefit.

The 1098-T underwent a makeover for tax year 2018, and it has improved significantly. However, some of the issues with the prior version of the form are still causing problems in 2018. This article outlines those problems and their solutions.

What Does the 1098-T Communicate?

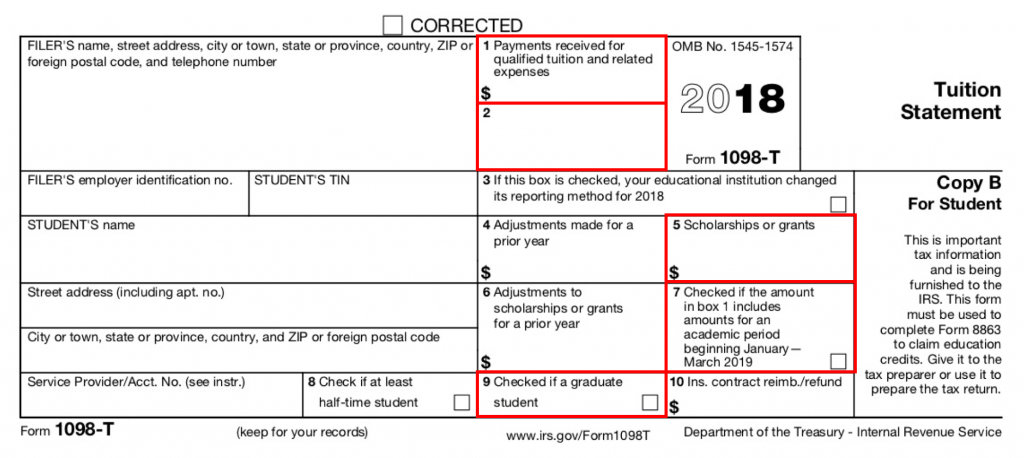

A few of the fields on the 1098-T are most relevant to funded PhD students.

Box 1 Payments Received

This box reflects the amount of money paid on your behalf or by you for tuition and related fees. For example, if your department pays for your tuition, the amount of the tuition will show up in Box 1.

Box 2 Amounts Billed

This box is no longer in use in 2018, but many (most?) universities used it until 2017. Box 2 also reflects tuition and related fees, but it is a sum of the charges billed in the tax year rather than the amounts paid. A bill could be issued in one tax year and not be paid until the subsequent tax year.

Box 5 Scholarships and Grants

This box reflects the scholarships, fellowships, and/or grants received by the student in the tax year. The money that paid your tuition and fees will show up in this box. The fellowship (or other non-compensatory income) that paid your stipend or salary may or may not be included in this box.

Box 7

This box is checked if any bills or payments for a term beginning in January through March of the following tax year were included on the current year’s 1098-T. For example, if your university received payment in December for a term starting in January, this box will be checked.

Box 9

This box is checked if you are a graduate student.

The remainder of this article reviews the problems with the 1098-T and how they can be ameliorated.

Receive Your Tax "Cheat Sheet"

Subscribe to the Personal Finance for PhDs mailing list for essential information to help funded US graduate students (citizens/residents) with their federal tax returns

Problem #1: Academic Year and Calendar Year Misalignment

Box 7 concerns the misalignment between the academic year and the calendar year.

Bills and Payments to Your Student Account

Ideally, the bills and payments for a given term will all show up on the 1098-T for the same calendar year in which the term falls.

Each fall term is like that: you may be billed or make a payment a month or two prior to the start of the term, e,g., in August for a term starting in September, but all the charges and scholarships and payments are done in the same calendar year.

However, for spring terms, you may be billed and perhaps make payments at the end of one calendar year for a term beginning in January to March of the next calendar year. In this case, the 1098-T for the earlier tax year is the one that reflects those expenses, and if a tax benefit is in order, it can be taken in the earlier year.

Historical Billing Practices for the 1098-T

In 2017 and prior, this caused a significant though largely unnoticed problem for funded graduate students (or anyone receiving scholarships): A university could post a bill for a spring term in December of the prior year, for example, and not post the scholarship that paid that bill until the start of the term in the later calendar year. That means that the earlier year would have an excess of expenses in Box 2, while the later year would have an excess of income. If not corrected, this could result in a tax deduction or credit in the earlier year and excess taxable income in the later year.

Imagine a typical fully funded graduate student at a university that had its accounting system set up this way and that used Box 2 on the 1098-T. (This was a common scenario.) In the student’s first calendar year, there would be two semesters of expenses billed but only one semester of scholarships posted. If the student used the numbers from the 1098-T without correction, he would be eligible for a tax break in that first year (or his parents would take it if he were a dependent). Each subsequent calendar year would have an equal number of terms of expenses and scholarships posted, which would probably result in small, not very noticeable discrepancies between the expenses and income. However, in the student’s final year, the system would catch up, and there would be scholarships posted with no corresponding expenses, resulting in excess income and excess tax due. In some cases, the extra tax due could exceed the value of the tax break taken in the earlier year. (Not to mention that if the student were a dependent in that first year his parents would have received the tax break, whereas he has to pay the extra tax himself in the last year.)

The correction that should have been performed throughout these years when a scholarship and the expense the scholarship paid showed up on different years’ 1098-Ts is to match up in the same calendar year the expense billed with the scholarship that paid the expense. Typically, that would mean not using an available tax benefit in an earlier year and preferring to use it in the later year that the income came in. When the expense and the scholarship that pays the expense are used in the same calendar year, the scholarship can be made tax-free using the expense if it is qualified. Specifically, you would report the relevant qualified education expenses in the later year rather than the earlier, meaning that the 1098-T in both years would be inaccurate / need adjustment.

What Changed in 2018?

Starting in 2018, Box 2 has been eliminated. This means that all universities now have to report payments received for tuition and related fees in Box 1. If the university switched its reporting system between 2017 and 2018, Box 3 is checked.

This is a much better system going forward for funded graduate students. It means that when a scholarship is posted to the student account to pay for tuition and related fees, that amount will show up in Box 5 and Box 1 in the same year, since they are the same action. It doesn’t matter if that happens in the same calendar year as the term or an earlier calendar year, because they will always be reported together.

However, this change causes two potential problems in 2018 for students at universities that made this switch.

1) If a charge was billed at the end of 2017 for a term stating in the first three months of 2018 and the bill was paid in 2018, the same expense will show up on both the 2017 and 2018 1098-Ts, first in Box 2 and then in Box 1.

Therefore, anyone receiving a 1098-T with Box 3 checked must determine whether one or more of the expenses summed in Box 1 was already used to take an education tax benefit in 2017. If that is the case, the expense cannot be used again in 2018.

2) This change in accounting systems also may force the unbalancing issue I described earlier for students finishing grad school. 2018 could be the year that there is excess income with no expenses available to offset it (after correction). If this happens, the student can either choose to pay the extra tax in 2018 or file amended returns going into the start of grad school when this problem originated (up to 3 years) to match up all the prior scholarships and expenses properly. This would still result in extra tax paid now, though it may be less than if the problem remained unamended.

The good news is that after catching up in 2018 if necessary, starting in 2019 the 1098-T will be much more straightforward.

Problem #2: Qualified Education Expenses Are Incomplete

The tuition and related fees reported on the 1098-T are not quite synonymous with the “qualified education expenses” you use to take an education tax benefit. In fact, there are different definitions of qualified education expenses depending on which benefit you use. Most likely, the amount listed in Box 1 is the amount of qualified education expenses the student has under the most restrictive definition for the Lifetime Learning Credit or the American Opportunity Tax Credit.

The definition of qualified education expenses for the purpose of making scholarship and fellowship income tax-free is more expansive. It includes certain required fees and expenses that were excluded from the definition of QEEs for the other education tax benefits, such as student health fees and required textbooks purchased from a retailer other than the university.

To find these additional qualified education expenses, check your student account, bank account, and saved receipts. Then, net them against your excess scholarship and fellowship income to make the income tax-free.

Problem #3: Not All Students Receive One

When Box 5 of the 1098-T exceeds Box 1 for a given student, the university does not have to generate a 1098-T. Some universities, as a courtesy, generate 1098-Ts for all students regardless of the Box 5 vs. Box 1 balance. This inconsistency generates confusion among graduate students and leads to the information in the student account being ignored.

Conclusion

It is clear that the 1098-T was not designed with funded graduate students in mind. Ideally, the 1098-T would be completely redesigned or a new form would be created to assist graduate students in preparing their tax returns. Until that happens, the 1098-T is not an independently useful document as it must be considered alongside the transactions inside and outside of the student account. The makeover to eliminate Box 2 was an improvement; at least starting in 2018, the 1098-T is no longer grossly misleading.