In this episode, Emily lists six things that your university isn’t telling you about your income tax. Point 1 is on why and how this lack of communication manifests. Point 2 is on what your Form 1098-T, if you even receive one, is not telling you. Points 3 through 5 are on the extra steps that grad students, postdocs, and postbacs on fellowships or training grants need to take but are rarely instructed on or even warned about. Finally, point 6 is on the tax pitfalls that anyone under age 24 needs to watch out for.

Links Mentioned in the Episode

- Tax Center for Personal Finance for PhDs

- How to Complete Your Grad Student Tax Return (and Understand It, Too!)

- Quarterly Estimated Tax for Fellowship Recipients

- Emily’s speaking services

- Season 2 Bonus Episode 1: Do I Owe Income Tax on My Fellowship?

- Season 4 Bonus Episode 1: Fellowship Income Is Now Eligible to Be Contributed to an IRA!

- Podcast hub

- Subscribe to the mailing list

Receive Your Tax "Cheat Sheet"

Subscribe to the Personal Finance for PhDs mailing list for essential information to help funded US graduate students (citizens/residents) with their federal tax returns

Intro

Welcome to the Personal Finance for PhDs Podcast: A Higher Education in Personal Finance. I’m your host, Dr. Emily Roberts.

This is Season 8, Episode 1, and I don’t have a guest today, but rather will list for you six things that your university isn’t telling you about your income tax. Point 1 is on why and how this lack of communication manifests. Point 2 is on what your Form 1098-T, if you even receive one, is not telling you. Points 3 through 5 are on the extra steps that grad students, postdocs, and postbacs on fellowships or training grants need to take but are rarely instructed on or even warned about. Finally, point 6 is on the tax pitfalls that anyone under age 24 needs to watch out for.

Please keep in mind that I’m recording and publishing this episode in early January 2021 for tax year 2020, so if you are listening to this at a later date, please check the Tax Center on my website, PFforPhDs.com/tax/ for any relevant tax law changes or other updates.

For Season 8 of the podcast, I’ve shifted up the format! There are two new short segments, one before and one after the interview or, in the case of this episode, expert discourse. I hope this new format will encourage more interactions between me and you, the listener!

Book Giveaway

Without further ado, here’s my episode on what your university isn’t telling you about your income tax. I have seven points for you today.

Preliminary Comments

Before we get into my list, I need to make a few general comments.

First, this episode is for US citizens and residents living and working in the US who have household incomes below about $150,000. I am discussing federal income tax only, but don’t forget that you might be subject to state and local income tax and other types of taxes as well.

Second, I am not a CPA or any kind of tax advisor, so none of this is advice for financial, legal, or tax purposes.

Third, I’m going to use the terms employee income and awarded income throughout the episode, so I need to define them for you up front because I semi made them up.

Employee income is the stipend or salary you receive in exchange for working for your university or institute. It is reported on a Form W-2 at tax time. Typically, employee positions at the graduate student level are called assistantships and max out at half-time positions.

Awarded income is the stipend or salary you receive from your fellowship or training grant, provided it is not reported on a Form W-2 at tax time. You are not considered an employee with respect to awarded income. Awarded income also includes the money that pays your tuition and fees if you are a funded grad student and your health insurance premiums if you are a postdoc or postbac non-employee. We’ll talk more about the tax forms awarded income may or may not show up on momentarily.

Fourth, if you want to learn more from me about any of the subjects I mention, the best place to go is PFforPhDs.com/tax/, where you can find many free articles, podcast episodes, etc. If you want to really dive in deep, I have two paid workshops available.

How to Complete Your Grad Student Tax Return (and Understand It, Too!) goes over how to handle your higher education income and expenses with respect to your tax return, whether you ultimately prepare it manually, using software, or through a human tax preparer. You can find that at PFforPhDs.com/taxworkshop/.

Quarterly Estimated Tax for Fellowship Recipients explains how you know if you’re responsible for paying quarterly estimated tax and goes line-by-line through the relevant tax form to show you how to estimate your tax due. You can find that at PFforPhDs.com/QEtax/. That’s q for quarterly. e for estimated, t, a, x.

Finally, if you want to bring this tax content and more to your peers at your university or institute, I am available for live speaking engagements. Head to PFforPhDs.com/speaking/ for more info on that.

All right! With that out of the way, here is my list of six things your university isn’t telling you about your income tax.

1. Anything

Your university is not telling you anything about your income tax. This can happen in one or both of two ways.

The first mode of non-communication is through tax forms or a lack of tax forms. Now, employees definitely will receive a Form W-2 at tax time that lists their stipend or salary. But the university isn’t necessarily required to send you any forms regarding your awarded income. It’s actually quite common for grad students and postdocs to receive zero tax forms or any kind of formal or informal communication regarding their income. And that obviously leaves them totally adrift, and many don’t even realize that they are supposed to account for their stipends or salaries on their tax return.

Not all universities take this zero communication approach for their PhD trainees receiving awarded income. A lot of them report grad student awarded income on Form 1098-T in Box 5, even though the IRS does not require them to. A minority report awarded stipends or salaries on Form 1099-MISC in Box 3. Some send an informal letter listing the amount of the awarded stipend or salary. These approaches are helpful to a degree, but it would be even better if there was one standard way of reporting awarded income that was used by all universities in the US.

The second mode of non-communication is through staff members. Almost universally, staff members are instructed to not discuss income tax with individual students or postdocs. The university does not want to make itself liable for erroneous tax returns. Even though that’s frustrating, I think it is understandable.

As a sidebar, despite this prohibition, grad students and postdocs frequently repeat misinformation to me that they heard from staff members. Now, whether the staff member said something incorrect or the student simply misinterpreted what was said, I can’t be sure. A perfect example is the phrase “Your stipend isn’t subject to income tax,” which many students have repeated to me. What I think the staff member said or meant to say is “Your stipend is not subject to income tax withholding.” However, what the student hears is “You don’t have to pay income tax on your stipend.” You can see that this is a topic that needs to be discussed carefully.

The best case scenario seems to be when universities host educational workshops on higher education tax topics. Those are typically led by knowledgable staff members, volunteers from local accounting firms, or me, an outside contractor. None of us are giving individual tax advice, but we are teaching grad students and postdocs how the university reports their income and higher education expenses and how the IRS views the same.

So super best case scenario, you receive some kind of tax form or letter and have the opportunity to attend a workshop. Worst case scenario, no forms or letters and everyone clams up.

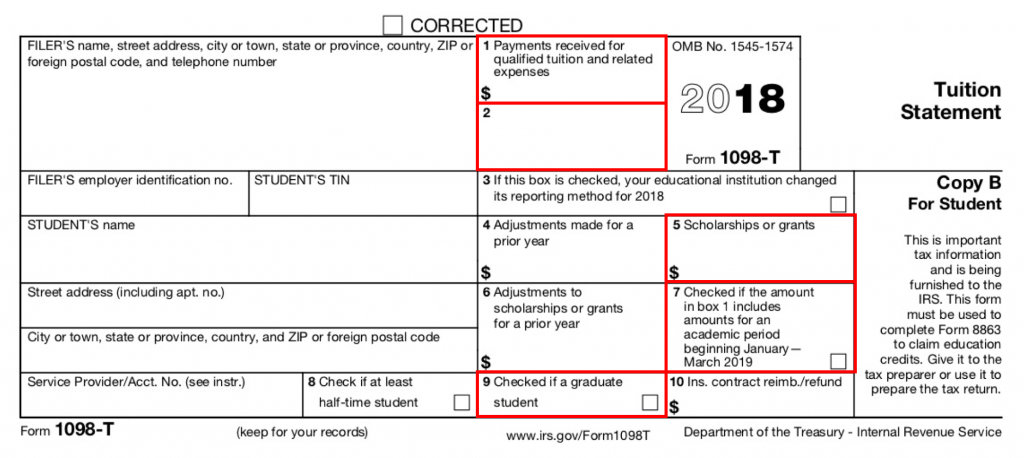

2. Your Form 1098-T Lacks Vital Information

I want to like Form 1098-T, I really do. It’s the best we have. And, without getting too much into the weeds, Form 1098-T has undergone a couple edits recently that make it far, far easier to use. So that is great. I wish its usage was universal.

Where Form 1098-T still falls short is in failing to catalog all awarded income and all higher education expenses that are relevant to a funded grad student.

On the income side, it’s typical to include tuition and fee scholarships and waivers in Box 5. Often, though not always, the awarded stipend or salary appears as well. But you might have received other awarded income as well during the year from your university or another source, and if that funding was not processed by the department that prepares the Form 1098-T, it may be left out. So you can look at the number in Box 5 of your 1098-T, but you still need to wrack your brain to come up with any additional awarded income you might have had for the year.

On the expenses side, Form 1098-T Box 1 reports “payments received for qualified tuition and related expenses.” A lot of people and software conflate the sum listed in that box with the total of their qualified education expenses for the year. Qualified education expenses are used to reduce your taxable income or your tax liability. I don’t want to get too technical in this episode, but if you make that assumption, you might be missing out on hundreds or even thousands of dollars of qualified education expenses, meaning you could overpay your true tax liability by tens or hundreds of dollars. This is because the definition of “qualified education expenses” is actually different depending on which higher education tax benefit you’re using them for, and Form 1098-T uses the most conservative definition. So unfortunately you can’t just go with the number listed in Box 1. You have to look into all of your higher education expenses individually to determine which you can use for the tax benefit you chose. That means combing through your student account as well as considering other spending you’ve done.

I wish Form 1098-T were completely trustworthy so you wouldn’t have to track down all the underlying expenses in your student account, but it’s just not the case right now.

If you would like some support through this process, I recommend joining my tax workshop at PFforPhDs.com/taxworkshop/. I provide a detailed discussion of what qualified education expenses are missing from Form 1098-T and worksheets to help you keep all the numbers straight.

3. Your Fellowship or Training Grant Income Is Taxable

I just wanted to close the loop I brought up in point #1. In case you were not aware, awarded income is taxable to the extent that it exceeds your qualified education expenses such as tuition and required fees.

Now, just because some income is taxable doesn’t mean you will actually end up paying income tax on it. If your total income is low enough or your have enough deductions and credits to claim, you may not end up paying any income tax. But you have to go through the exercise of filling out your tax return to determine if and how much income tax you owe, and that is true whether your income is awarded or employee or both.

There is a persistent rumor within many universities and departments that awarded income is tax-exempt. That actually used to be the case several decades ago, so there is a kernel of outdated truth in the rumor. And I can understand why the rumor lives on and spreads, because it is what people want to hear. Plus, at many places it is not countered by direct communication from the university as in point #1.

If you would like to hear my full argument with IRS references to prove that awarded income is taxable, please listen to Season 2 Bonus Episode 1 of this podcast, titled “Do I Owe Income Tax on My Fellowship?” It is linked from the show notes for this episode.

4. Your Paycheck Is Pre-Tax, Not Post-Tax.

I’m going to expand on the issues related to awarded stipends and salaries now.

With employee income, your employer withholds income tax on your behalf to send to the IRS and gives you a paycheck for the rest of your income, which is your net or after-tax income. A pay stub is also generated for each paycheck that lists your gross income and all the tax that has been withheld, though you might have to proactively seek it out.

While it is possible to withhold income tax from awarded income, most universities and institutes don’t offer this benefit. There is typically no pay stub generated, either. In the absence of clear communication, harkening back to point #1, many, many fellows who are on board with point #3 assume that their income has already had income tax withheld. After all, that is how paychecks work for the great majority of people who receive them.

It’s a nasty surprise when they realize that their pay is pre-tax, not post-tax, and they have a large tax bill to pay.

5. Your Income Tax Is Due Four Times per Year, Not One

This point follows on on from point #4 for those who do not have income tax withheld from their awarded stipends or salaries:

If the amount you owe in income tax exceeds $1,000 for the year and you don’t fall into an exception category, you are required to make what are called estimated tax payments. This is when you, personally, send the IRS money up to four times per year to stand in for income tax withholding.

Going along with point #1, this is rarely discussed or even mentioned to grad students and postdocs receiving awarded income. A heads up would be nice.

Ideally, fellowship recipients would be told that they might owe income tax—point #3—and that tax is not being withheld from their paychecks—point #4—and that the best practice is to set aside money from each paycheck for their future tax payments, whether that is once per year or up to four times per year—this point.

If you would like more information about estimated tax for fellowship recipients, I have a great long-form article on it that I’ll link to from the show notes. If you want my help to determine if you are required to make estimated tax payments and in what amount, I recommend checking out my workshop at PFforPhDs.com/qetax, that’s qe for quarterly estimated t a x.

6. Those of You Under Age 24 Need to Be Extra Cautious

If you are under age 24 at the end of the tax year and receive primarily awarded income, there are two tax potholes for you to watch out for. Your university won’t tell you about these subjects because it comes way too close to giving tax advice.

The first is potentially being claimed as a dependent by your parent or other relative, which generally speaking is not good for your bottom line but good for theirs. I have observed that parents and the people who prepare their tax returns tend to default to assuming that anyone under age 24 who is a student is a dependent. The thing to know about being claimed as a dependent is that it’s not a matter of preference. There is a set of five objective tests to determine if a young person is a dependent, which you can read about in Publication 501. There is a tricky part of one of the tests, though, the support test, which is different depending on if your stipend or salary is employee income or awarded income, so watch out for that. You should go the extra mile to discuss with your parent or relative whether you can be claimed as a dependent before either of you files in case there is a difference of opinion to work out, because it’s much easier to do it that way than to mediate a disagreement via the IRS.

The second is the Kiddie Tax. The Kiddie Tax is an alternative way of calculating your tax liability based on your parent’s marginal tax rate instead of your own graduated tax rates. Ostensibly, the Kiddie Tax is supposed to disincentivize high-earning parents from sheltering income-generating assets in their children’s names, but in a mind-boggling twist, the Kiddie Tax applies to awarded income, not just investment income. I have an article on my site on the Kiddie Tax linked from PFforPhDs.com/tax/. I sincerely hope that it does not apply to you or you can find a way to avoid it or minimize it, but in any case it is something to be aware of and watch out for.

I have a whole video in How to Complete Your Grad Student Tax Return (and Understand It, Too!) dedicated to people who were under age 24 during the tax year, so if you want a more in-depth exploration of these topics, please go to PFforPhDs.com/taxworkshop/.

Conclusion

I’m really glad you joined me for this episode! If you found something of value in it, please share it with your peers. You can save them a lot of emotional and financial turmoil and stress by giving them a heads up about the topics I covered. I really appreciate it! Good luck this tax season, and don’t hesitate to reach out if you need any help!

Listener Q&A

Outro

Listeners, thank you for joining me for this episode!

pfforphds.com/podcast/ is the hub for the Personal Finance for PhDs podcast. On that page are links to all the episodes’ show notes, which include full transcripts and videos of the interviews. There is also a form to volunteer to be interviewed on the podcast and instructions for entering the book giveaway contest and submitting a question for the Q&A segment. I’d love for you to check it out and get more involved!

If you’ve been enjoying the podcast, here are 4 ways you can help it grow:

- Subscribe to the podcast and rate and review it on Apple Podcasts, Stitcher, or whatever platform you use. If you leave a review, be sure to send it to me!

- Share an episode you found particularly valuable on social media, with a email list-serv, or as a link from your website.

- Recommend me as a speaker to your university or association. My seminars cover the personal finance topics PhDs are most interested in, like investing, debt repayment, and taxes.

- Subscribe to my mailing list at PFforPhDs.com/subscribe/. Through that list, you’ll keep up with all the new content and special opportunities for Personal Finance for PhDs.

See you in the next episode, and remember: You don’t have to have a PhD to succeed with personal finance… but it helps! The music is “Stages of Awakening” by Podington Bear from the Free Music Archive and is shared under CC by NC.