As you are no doubt aware, graduate students are clamoring for information on investing for retirement. I’ve observed this during my seminars and it’s been documented by the Council of Graduate Schools’ Financial Education. Graduate students are wondering how to get started saving for retirement during graduate school or want to be prepared to start immediately following graduate school. Roth IRAs are an integral component of preparing for retirement for graduate students. This article covers everything you need to know about Roth IRAs in graduate school: what an IRA is, why you should use one, the differences between traditional and Roth IRAs, the type of income you need to contribute to an IRA, how much to contribute to an IRA, and how to open an IRA.

If you want to know with which firm I have my own IRA and in what I’m invested, sign up for my mailing list to receive a unique 700-word letter. If you have any remaining questions on Roth IRAs in graduate school after reading the article, leave them in the comments or email them to me; I’ll respond directly and update the article with the answer.

Free Email Course: Investing for Early-Career PhDs

Sign up for the mailing list to receive the free 10,000-word email course designed for graduate students, postdocs, and PhDs in their first Real Jobs.

The information in this article is current as of 2023.

What Is an IRA?

IRA stands for Individual Retirement Arrangement. It is a tax benefit offered by the US federal government to incentivize saving for retirement. Anyone with taxable compensation (or a spouse with taxable compensation) can contribute to an IRA; it is not a benefit offered by your workplace like a 401(k) or 403(b). The contribution limit to an IRA in 2023 is $6,500 ($7,500 for people aged 50 and older) or your amount of taxable compensation, whichever is lower.

An IRA is not synonymous with particular investments; you buy investments inside (or outside) of your IRA. An IRA (and other tax-advantaged retirement accounts like a 401(k) or 403(b)) is like a shield that protects your investments from taxes.

If you invest in a regular taxable investment account, every year that you realize a gain you will pay some tax on the gain. This tax effectively suppresses the growth rate you see on your investments, which saps the power of compound interest. An IRA or other tax-advantaged account maximizes that growth rate by eliminating the tax, which ultimately maximizes the amount of money you have in your investments.

However, this tax-advantaged status comes with a trade-off. The purpose of an IRA is to help Americans save for retirement, so there are restrictions on when and for what purpose you can remove money from your IRA. In limited cases, you can remove money from your IRA without incurring any penalty, but in general you have to wait until you are 59.5 years old.

Why Use an IRA Instead of a Taxable Investment Account?

If you were to save for the long-term into a normal investment account, every year you would pay some tax on the gains you realized in the account. If your account had a great deal of turnover in the course of a year, you would pay your marginal tax rate on the gains (10%, 12%, 22%, etc.) plus whatever state tax would be due. If your account had very little turnover, your tax rate(s) would be lower. If instead your money was in an IRA (or a similar tax-advantaged retirement account like a 401(k) or 403(b)), all the gains would be tax-free.

Taxes on a regular investment account amount to death by a thousand cuts. Every year, a fraction of the growth (if there was growth) is removed through taxes and no longer serves as part of the principal for the growth in a subsequent year. Using a tax-advantaged account like an IRA allows the growth to continue unfettered. Over many decades, the balance in an IRA can be hundreds of thousands of dollars larger than the balance in a taxable account to which the same contributions were made.

Further reading: Taxable vs. Tax-Advantaged Savings

For short- or medium-term investing goals, taxable accounts are appropriate because of the complete accessibility of the money contributed. But for long-term investing goals such as retirement, it is very advantageous to use an IRA or other tax-advantaged retirement account.

Why to Contribute to an IRA during Graduate School

Graduate students have a limited income and plenty of claims on that income. They must first and foremost pay for their basic living expenses, which not all stipends can even cover. If there is any money remaining, the student must choose among upgrading his lifestyle, saving up cash, paying down debt, investing, giving, supporting family members, etc. They may very well have higher priorities than saving for retirement. However, there is a very compelling reason for starting to invest for the long term if possible: the power of compound interest aka the time value of money.

As graduate students are most often in their 20s or 30s, time is currently on their side with respect to investing. Many Americans put off saving for retirement until their peak earning years in their 40s and 50s, but the advantage of starting earlier is that you need to save less money overall to reach the same endpoint. This is the time value of money: the money that you invest today is worth more than the money you invest years from now because the intervening time adds value. Investing even small amounts of money during graduate school can massively add to your wealth in retirement, much more so than large amounts of money saved later on.

The mechanism of the time value of money is the power of compound interest.

In qualitative terms, this is how compound interest works: In year 1, you invest some money and it earns a return (we’ll say a positive return, to keep things simple). In year 2, you invest more money which earns a return, plus your contribution and the return from the previous year also earn a return. In year 3, you invest more money and it earns a return, plus your contributions and earnings from previous years earn a return. Before you know it the increases to your account balance each year are coming more so from the growth your previous contributions than on your current contributions; after decades, most of your account balance will be due to growth rather than your direct contributions.

The power of compound interest is modeled by this equation, which represents exponential growth:

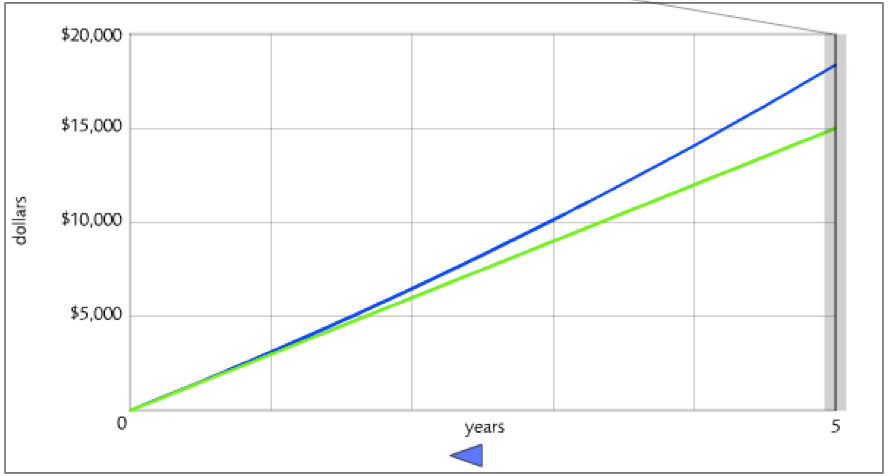

Using the equation for compound growth, you can get an idea of how much money can grow with a given rate of return and time period. In real investing in the stock market, you will not receive the exact same rate of return each year like clockwork; in some years you will lose money, in others you will see a very high return, and everything in between. But on balance, over long periods of time, the math of compound interest reveals the scale of growth possible with even an irregular return like you would see from the stock market. (Investments that give a regular and guaranteed rate of return, such as bonds and certificates of deposit, are comparatively low-returning and not usually considered appropriate long-term investments for a young person.)

For example, if you invested $250 per month at an 8% average annual rate of return for five years during graduate school, in that time you would contribute $15,000 and your ending balance would be $18,369.21. The growth over that time period is nice but not staggering.

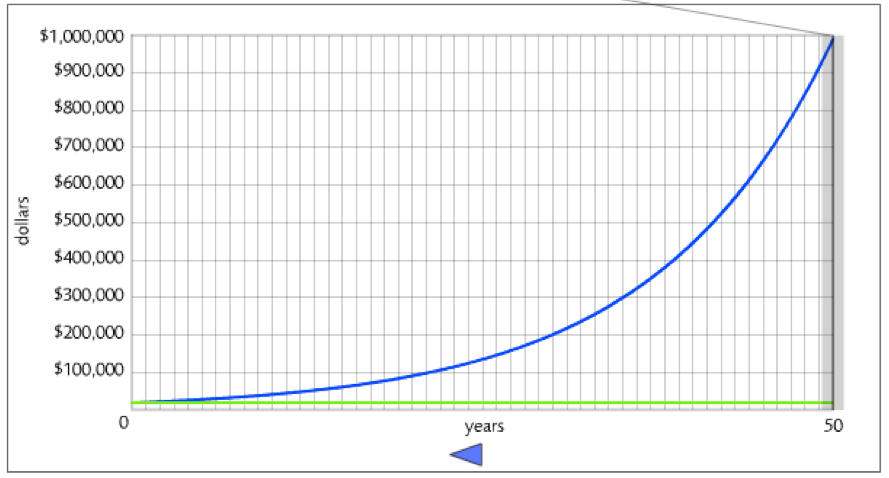

But if you then leave that money alone to continue compounding at 8% per year for 50 years – make no additional contributions – your money grows to a mind-boggling $989,688.35!

That’s an extra one million dollars in retirement that you would not have had if you had not started investing during graduate school!

The numbers above are for illustrative purposes only. It’s still incredibly worthwhile to begin investing during graduate school even at a rate of less than $250/month. Compound interest works the same on any sum of money, whether $5 or $5,000. The point is that investing with time on your side turns small amounts of money into large amounts.

Further reading:

- Whether You Save During Graduate School Can Have a $1,000,000 Effect on Your Retirement

- Why You Should Invest During Graduate School

- Even Grad Students Should Have a Roth IRA

Free 10,000-Word Email Course on Investing for Early-Career PhDs

Subscribe to our mailing list to receive the 6-day email course designed for graduate students, postdocs, and PhDs in their first Real Jobs.

The Difference between Traditional and Roth IRAs

When you open an IRA, you have the choice between opening a traditional IRA and a Roth IRA. (You can contribute to either/both in the course of a year, but the maximum contribution limit applies to them both together, not each separately.) There are a number of differences between the two types of IRAs, especially when it comes to eligibility and withdrawing money in retirement, but there are two key differences that are most salient for young people who are eligible for both types: when you pay income tax and how to withdraw money without penalty prior to age 59.5.

Further reading:

When You Pay Income Tax

With both types of IRAs, you won’t pay any tax while the money is growing inside the IRA.

With a traditional IRA – unsurprisingly, the first type introduced into the tax code – there is an additional tax incentive upon contribution to the IRA, which is that you exclude the amount you contribute from your taxable income for the year (take a tax deduction). You take a tax deduction on the money you contribute, then your money grows tax-free, and then you pay ordinary income tax on the amounts you withdraw each year in retirement. The traditional IRA is a mechanism of tax deferral.

The Roth IRA is the newer type of IRA (named after the senator who introduced it). The tax break on the Roth IRA is the flip of the one for the traditional IRA. You pay the full income tax due on the contribution you make to the Roth IRA, then your money grows tax-free, and you withdraw it tax-free in retirement.

The key to choosing between a traditional and Roth IRA is to guess when you will pay a lower tax rate: upon contribution or withdrawal.

One way to approach this question is by considering when you will be in a lower marginal tax bracket: now or in retirement? The rationale behind this is that you are going to get the tax break on the last dollars of your income, which are likely to fall in your marginal tax bracket. You know your marginal tax bracket today; most graduate students without outside sources of income fall in the 12% marginal tax bracket or even lower (plus your marginal state tax rate). But you have to guess whether the marginal tax bracket you will fall into in retirement will be higher or lower. In the intervening decades, you will experience personal changes in your income and tax bracket, and there are likely to be legislative changes to the tax code and rates.

This guess is probably easier for graduate students than for the average American. Graduate students can make the reasonable assumption that their current income is much lower than their income will be throughout their careers and likely also in retirement. (Ask yourself: Do you want to be living the same lifestyle in retirement that you are in graduate school or would you like it to be more lavish?) Whatever might happen to the tax code more broadly, confidence that you are in a personal low-income and low-tax bracket period is a strong argument for the Roth IRA over the traditional IRA. I and virtually every graduate student I’ve spoken with about this issue chose the Roth IRA over the traditional IRA during grad school.

However, there are more nuanced arguments that you might consider that are more in favor of the traditional IRA, even for someone in a low tax bracket currently. Such arguments are beyond the scope of this article, but there is plenty of reading material available on the decision between the traditional and Roth IRA for you to dive into if you are interested.

Further reading: Traditional vs. Roth IRA: The Unconventional Wisdom

Penalty-Free Early Withdrawal

One of the big planning/psychological barriers to beginning to save for retirement is the nagging question “What if I turn out to need the money in the near future?” After all, life is unpredictable; sustained loss of income or a very expensive emergency might be just around the corner. Some people find it difficult to put barriers between themselves and their money no matter what degree of cash they may have accessible in an emergency fund or other savings. The prospect of sequestering money that can only be used many decades from now in retirement can be daunting.

The Roth IRA (as opposed to the traditional IRA) helps to alleviate this anxiety. While it is rarely a good idea to take already-contributed money out of an IRA (after all, you are unplugging that money from the power of compound interest), you do have that option with the Roth IRA. Because you have already paid your income tax on your Roth IRA contributions, you can withdraw those contributions at any time without penalty (or additional tax). Certain conditions must be met to withdraw earnings early without penalty or tax. For one example of a qualified distribution, the IRA must be at least five years old and the withdrawal is used to buy a first home (up to $10,000); there are other conditions that create qualified distributions as well.

With a traditional IRA, on the other hand, early withdrawals always result in tax due, and penalties are also assessed if the withdrawal is not qualified.

The Type of Income You Need to Contribute to an IRA

Only “taxable compensation” (formerly “earned income”) can be contributed to an IRA; while IRAs are independent of your workplace, they are not independent of work. For most Americans, this is a non-issue, because they work for their income. For example, they might be employees receiving W-2 income or self-employed; both of these types of income are taxable compensation.

Up through 2019, taxable fellowship income not reported on a W-2 was not considered taxable compensation. Starting in 2020, taxable fellowship income not reported on a W-2 is considered taxable compensation. That means that a graduate student receiving a stipend is eligible to contribute their stipend income to an IRA, whether that stipend is reported on a W-2 or some other form (or not at all)—as long as it is taxable in the US.

If none of your income is taxable in the US because you are a nonresident and benefit from a tax treaty, you don’t have “taxable compensation” and are not eligible to contribute to an IRA.

Further reading:

Free Email Course: Investing for Early-Career PhDs

Sign up for the mailing list to receive the free 10,000-word email course designed for graduate students, postdocs, and PhDs in their first Real Jobs.

How Much to Contribute to an IRA during Graduate School

The right amount of money to contribute to an IRA in a given year of graduate school might be $6,500, $0, or somewhere in between.

Graduate school is an extraordinary time of investment in one’s career, possibly to the exclusion of investing for retirement. While many graduate students are paid stipends that more than cover their living expenses, some graduate students are either not being paid a living wage or have unusually high expenses (e.g., have dependents).

To determine the right amount for you to contribute to an IRA, you must explore your means and your goals.

Means: How does your stipend compare to the local living wage? While the local living wage will not exactly match your expenses in every category, it should give you a sense of the baseline cost of living in your county or metro area. If your stipend is at or above the living wage and you aren’t able to save anything, try to reduce your expenses so you can start to invest or accomplish other financial goals. If your stipend is below the living wage, you may not have the means to start saving or investing right now; getting through graduate school without accumulating debt may be an appropriate financial goal.

Goals: Not all graduate students with discretionary income should jump right into investing. There may be higher-priority financial goals such as paying off high-interest debt or saving cash for emergencies or short-term expenses. But if investing for retirement becomes your top financial goal or a goal you work on concurrently with other goals, it is appropriate to contribute to an IRA.

If a graduate student does have the means to invest and investing is their top financial goal, rules of thumb come back into play. The most common (mainstream) retirement savings rates bandied about in the personal finance community are between 10 and 20% of income (gross or net). I think investing 10% of gross income into a Roth IRA is a great initial goal for a graduate student; it was my retirement savings rate when I started graduate school. It may be one easily reached (especially if you build it into your budget from the beginning) or quite challenging. If it takes you years of budget optimization to reach 10% (or you never do), that’s fine. If you want to go higher than 10%, that’s great too, and you’ll have a wonderful nest egg when you transition out of graduate school. (My husband and I reached a 17.5% savings rate from our gross income by the time we defended, but it took years to raise our savings rate to that point.)

A higher retirement savings rate will help you reach financial independence faster, but you always have to balance that against your quality of life in the present. But if you have the means and aren’t working on a more pressing goal, I do recommend regularly contributing to a Roth IRA during graduate school, even if it’s a small percentage. Getting into the habit of saving for retirement is as valuable as the savings itself; if you save during graduate school, once you have a Real Job you’ll never be able to tell yourself that you “can’t afford to save right now.”

Further reading:

How to Open an IRA

The actual process of opening an IRA is straightforward, but choosing where to open it and what to invest in inside the IRA will take some research and decisions on your part.

Briefly, using index funds (a passive investing strategy) is the most effective, least expensive, and most time-efficient manner of investing. You can buy index funds (e.g., the S&P 500 index fund) or a fund of index funds such as a target date or lifecycle fund at any number of brokerage firms. (Brokerage firms that specialize in trading single stocks, i.e., the ones you probably see the most advertisements for, may not offer index funds.)

When you select a brokerage firm, you need to ensure that: 1) it allows you to open an IRA, 2) it offers the investments you are looking for, 3) it is not too expensive to own the funds, and 4) you can meet the account minimums. Index funds are inherently inexpensive, but there will still be some price differences among brokerage firms. Different firms also set different account size minimums, such as between $1,000 and $3,000, but some waive these minimums if you set up an automatic savings rate into the account.

Further reading: Brokerage and IRA Account Minimums

Once you have selected your brokerage firm and investment, you are ready to open your IRA. You should be able to complete the process online in just a few minutes, and the brokerage firm’s website will guide you through the process. You will be asked for your personal information such as your name, SSN, and address. Once you have the IRA open, transfer in the amount of money you need to open the account and/or set up an automatic savings rate, and choose the investment(s) you want to buy with your money.

Join Our Phinancially Distinct Community

Receive 1-2 emails per week to help you take the next step with your finances.

Can a grandfather or father start a ROTH IRA FOR A Child who is in school or internship regardless of child’s income. I’d like to start with the highest amount allowed?

The person whose name the IRA is in has to have taxable compensation in the tax year. If your grandchild has taxable compensation, you can gift your grandchild the money you want them to contribute.

Thank you for this great summary! I started a Roth IRA many years ago, when I was in a job without an employer-sponsored retirement account and making a lot less money than I do now. When I start my full-time PhD program this fall, my combined family income will be just outside of the IRS limit for being able to open a Roth IRA. However, can I still contribute to the Roth I already have? Or do I need to open a separate, non-Roth IRA?

Thank you for your thoughts on this!

Erin

If you’re disallowed from contributing to a Roth IRA in 2020 based on your income, you can’t use an old Roth IRA. You need to use a traditional IRA (if eligible) or a backdoor Roth IRA (https://www.nerdwallet.com/blog/investing/backdoor-roth-ira-high-income-how-to-guide/).

Ok I have a question – I’m an undergrad that is paid for research via this https://www.nigms.nih.gov/training/MARC/Pages/USTARAwards.aspx program. Am I eligible for Roth IRA contributions based on this? The wording of the law says it applies to people in graduate school or postdoc OR RESEARCH so to me it sounds like I should count?