In this episode, Emily teaches what various types of PhD trainees can do at the start of the academic year to make next tax season go more smoothly. She covers tracking qualified education expenses, quarterly estimated tax, the Kiddie Tax, and state residency. Please consider sharing this episode on social media or with an email list-serv so your peers have access to this information as well!

Links Mentioned in the Episode

- How to Prepare Your Grad Student Tax Return (Tax Year 2020)

- What Your University Isn’t Telling You About Your Income Tax

- Do I Owe Income Tax on My Fellowship?

- Quarterly Estimated Tax for Fellowship Recipients

- Fellowship Income Can Trigger the Kiddie Tax

- How to Complete Your Grad Student Tax Return (and Understand It, Too!)

Introduction

Welcome to the Personal Finance for PhDs Podcast: A Higher Education in Personal Finance. I’m your host, Dr. Emily Roberts.

This is Season 10, Episode 2, and I don’t have a guest today, but rather I will tell you what various types of PhD trainees can do at the start of the academic year to make next tax season go more smoothly. We will discuss tracking qualified education expenses, quarterly estimated tax, the Kiddie Tax, and state residency. Please consider sharing this episode on social media or with an email list-serv so your peers have access to this information as well!

We are at or near the start of a new academic year, which means it’s time to take a moment to think about taxes. A few minutes of consideration at this time of year can save you a big headache and wallet-ache during tax season, so it’s worth it.

This episode has four sections, and I’m going to clearly identify at the beginning of each section who the information is for, because it will switch around. Overall, this episode is for US citizens, permanent residents, and residents for tax purposes living in the US. The various intended audiences for the sections are full-time graduate students; postbacs, grad students, and postdocs receiving non-W-2 stipends or salaries; full-time graduate students age 23 and younger; and grad students who either moved states in 2021 or whose income is coming from a new state. Our overarching topic is what you can do now to make next tax season easier.

Please note that I am not a Certified Public Accountant or Certified Financial Planner. This content is educational in nature only and should not be considered tax, financial, or legal advice for any individual. You are entirely responsible for your own financial decisions.

Tracking Education Expenses

Section A is for full-time graduate students.

In early 2022, once you get into preparing your annual tax return, you are going to need to use your so-called “qualified education expenses.” You can use these expenses to reduce your tax liability. Depending on which higher education tax benefit you employ, your qualified education expenses will either be used as a deduction or a credit. I’m not getting into all the details now because you will figure that out during tax season, but if you want to read more, go to PFforPhDs.com/prepare-grad-student-tax-return/ for my article updated for 2020.

The action step for you at this point in the year is to keep track of any education expenses that you suspect might be qualified education expenses. Now, the education expenses that are paid through your student account are already tracked for you, and you should be able to access your 2021 statement during tax season to look at all of the transactions for items like tuition and fees. What I’m suggesting that you manually track is any education expense that you transact outside of that student account, such as textbooks, course-related expenses, and computing purchases.

What I mean by tracking is to save two types of documents: 1) The receipt of the purchase showing the price paid. 2) The document stating that the purchase was required by your course instructor, your department, your school, or your university. The document could be a course syllabus, an email, or a screenshot from a webpage. You can choose how you want to save these records, but I suggest a digital copy maintained in cloud storage.

Now, not every education expense that you track may turn out to be a “qualified education expense” as that will depend on which higher education tax benefit or benefits you choose to use for your tax return. I suggest you leave the task of figuring out what is qualified and what is not to Future You. Present You only has the responsibility to track the expenses, and Future You will thank you for that.

Awarded Income and Estimated Tax

Section B is for postbacs, grad students, and postdocs receiving non-W-2 stipends or salaries.

Right up front, I need to define what I mean by a non-W-2 stipend or salary. I use a framework wherein there are two basic classifications for a stipend or salary that a PhD trainee might receive: employee income and awarded income. These are my own terms, so you won’t find ‘awarded income’ in IRS documentation or used by universities.

Employee income comes from the work than an employee performs for their employer. At the graduate student level, employee positions are often but not exclusively called assistantships, e.g., research assistantship, teaching assistantship, or graduate assistantship. If you have employee income and are a US citizen, permanent resident, or resident for tax purposes, this income will be reported on a Form W-2 at tax time.

The other type of income, awarded income, is more difficult to define. It is given as an award rather than for work performed. At the postbac, grad student, and postdoc levels, awarded income is often but not exclusively called fellowship income. If you are a US citizen, permanent resident, or resident for tax purposes, this income could be reported on a Form 1098-T, a Form 1099-MISC, a Form 1099-NEC, or a courtesy letter. However, there is actually no IRS reporting requirement for this type of income, so many PhD trainees receive absolutely no documentation whatsoever.

If you want to understand this framework more fully, I suggest listening to Season 8 Episode 1 of this podcast, which is titled “What Your University Isn’t Telling You About Your Income Tax.”

Now, the important things to know about awarded income, which I also call non-W-2 stipends or salaries, at this time of year are that 1) this is taxable income and 2) your university is likely not withholding income tax from your paychecks.

There are endemic rumors running around universities that this non-W-2 type of income is not taxable. While it is very tempting—and self-serving—please do not believe these rumors. Listen to Season 2 Bonus Episode 1 of this podcast, titled “Do I Owe Income Tax on My Fellowship?”, in which I clearly delineate which portion of your awarded income is taxable and which is tax-free.

One of the reasons these rumors sound believable is that, with rare exceptions, universities and institutes do not withhold income tax on behalf of their non-employees.

If your stipend or salary recently switched to an awarded income source or this is the first time you’re learning about this income tax issue, you have a few action items:

1) Figure out if income tax is being withheld from your paychecks. If it is, you’re done until tax season.

If income tax is not being withheld:

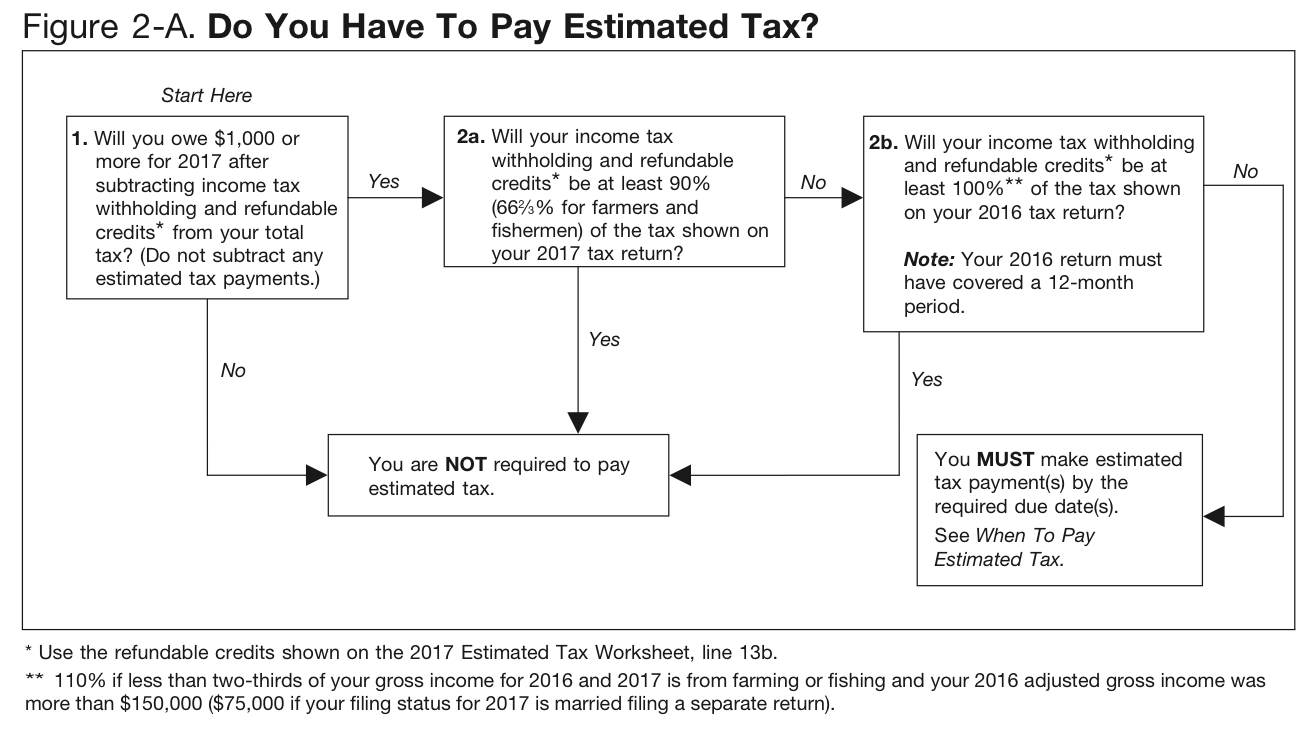

2) Fill out the Estimated Tax Worksheet on p. 8 of Form 1040-ES. Essentially, you will do a high-level draft of your 2021 tax return, and the worksheet will tell you whether you are required to pay estimated tax and if so in what amount. The principle behind estimated tax is that the IRS expects to receive income tax payments from each taxpayer throughout the year as they receive their paychecks. If your employer does not withhold income tax on your behalf, this becomes your responsibility. However, there are some situations in which estimated tax is not required, and the Estimated Tax Worksheet will tell you if you fall into one of the exception categories. If you are required to pay estimated tax, please be aware that the next due date is September 15, 2021. The due dates typically fall in mid-April, mid-June, mid-September, and mid-January of each year. If you are required to pay estimated tax and fail to, you may be fined by the IRS.

3) Whether you are ultimately required to pay estimated tax or not, the Estimated Tax Worksheet will tell you how much you can expect to pay in tax above your withholding for the year. I strongly encourage you to start saving up for your eventual tax payment or payments. Divide your additional tax liability in Line 14b by the number of remaining paychecks you’ll receive in 2021 and start saving that amount of money from each paycheck. Personally, I have a dedicated savings account named Taxes into which I transfer money from each paycheck. Then, when my quarterly bills are due, I have the money ready to go, and the payment doesn’t strain my cash flow at all.

Please keep in mind that if you have a state tax liability in 2021, you may be required to pay estimated tax to your state as well.

If you want some help with filling out your Estimated Tax Worksheet, please check out my workshop, Quarterly Estimated Tax for Fellowship Recipients at PFforPhDs.com/QEtax/. The workshop explains how to fill out every line of the Estimated Tax Worksheet plus how to handle common scenarios that PhD trainees encounter, such as switching onto or off of fellowship mid-year and being married to someone who has income tax withholding. The workshop comprises numerous pre-recorded videos, a spreadsheet, and an invitation to the next live Q&A call, which will take place on September 12, 2021. To join the workshop, go to PFforPhDs.com/QEtax/. That’s q for quarterly, e for estimated, t a x.

By the way, I give a discount for bulk purchases of this workshop, and it’s not too late to ask your department, graduate school, graduate student association, postdoc office, etc. to buy it on behalf of a group of graduate students, postdocs, or postbacs. Simply email me at emily at PFforPhDs dot com to get the ball rolling on that purchase.

Commercial

Emily here for a brief interlude!

We have a special event coming up on Friday, August 27, 2021! It’s the fourth installment of my Wealthy PhD Workshop series. The subject is debt repayment.

This workshop is for you if you are in debt of any kind and want to learn the best strategies for getting out of debt. These strategies are tailored to the PhD experience, particularly that of graduate students. We will cover student loans, of course, which are such a complex topic, as well as mortgages, credit card debt, auto debt, medical debt, etc. I’ll give you a spreadsheet that will help you work through in which order to tackle your debts, taking into account the type of debt, the interest rate, and the payoff balance. We’ll also discuss how to sustain your motivation through a long debt repayment process.

This is going to be a value-packed session, so please join us on August 27th. You can register at PFforPhDs.com/WPhDDebt/. That’s PF for PhDs dot com slash W for Wealthy P h D D e b t.

Now back to our interview.

The Kiddie Tax

Section C is for full-time graduate students age 23 and younger.

I want to give you a heads up that a higher tax rate might apply to you if you meet the following criteria:

- You are age 23 or younger on 12/31/2021.

- You are a full-time student.

- You receive a non-W-2 stipend or salary for at least part of 2021.

If you checked all of those boxes, you might be subject to the Kiddie Tax, which means that part of your income may be taxed at your parents’ marginal tax rate instead of your own. The Kiddie Tax can apply even if you aren’t being claimed as a dependent.

I can’t say for sure that you will or will not be subject to the Kiddie Tax as there are more calculations that have to be performed, but I suggest that you look into this before the end of the calendar year and possibly take some mitigation measures if your parents’ marginal tax rate is higher than yours. You may need to engage a professional tax preparer to help you and your parents with tax planning and preparation for 2021. You may need to save more from each paycheck for your eventual tax bill than I laid out in Section B.

I have an article about how the Kiddie Tax affects funded PhD students at PFforPhDs.com/kiddietax/. That P F f o r P h D s dot com slash k i d d i e t a x.

State Residency

Section D is for graduate students who moved states in 2021 or are receiving income from a new state.

I find that people get rather mixed up about state residency and taxes, especially when they are in graduate school. For a traditional college student who is a dependent of their parents, it is common to maintain your residency in the state your parents live in even while you attend college in another state. However, I rarely come across a compelling reason that a graduate student should do the same.

The pandemic has also thrown a wrench into the question of state residency due to how common remote work is now. So even if you lived in only one state in 2021, if your income comes from a different state, that’s something to contend with.

What I think you should do at this time of year to make tax season easier is to figure out and/or decide in which state or states you will be a resident, part-year resident, or non-resident in 2021. This will require you to read about how your new state and your old state define residency and how they tax residents, non-residents, and part-year residents.

My totally generic, blanket recommendation if you have moved states to start grad school is to consider yourself a resident of your new state, even if technically your former state allows you to still be considered a resident due to your student status. You’re a full-fledged adult with a more-or-less proper income now. Why would you want to keep close ties to your parents’ address? In almost all cases, there is no financial advantage to doing so plus you’ll likely have to file two state income tax returns, one as a non-resident in the state you live and work in and one as a resident in the state you don’t live or work in. For how long do you want to keep that up?

If you agree that you don’t want to keep filing two returns indefinitely if there’s nothing in it for you, take a few steps this fall to firmly establish your ties to your new state. Reference how your new state defines a resident for the definitive word on how to do so, but for some starting ideas you should get a new driver’s license, register to vote, change your address with your car insurance, and update your mailing address with all your financial institutions.

Now, if you really do have a compelling reason for maintaining your residency in your old state while you’re a student, by all means try to do so. You still have to read all the material I mentioned before, but this time with the goal to maintain your residency in your old state and avoid being considered a resident in your new one. By the way, in all my conversations with grad students about taxes, I’ve only ever heard one reason that I considered compelling: A resident of Alaska who was attending graduate school in another state wanted to maintain their Alaska residency so they could continue to receive universal basic income. Please remember that even if you do have a great reason to want to maintain residency in your old state, you have to cross all your ts and dot all your is to make sure you meet the requirements.

Conclusion

That it for this episode! I hope you’ll check in with me during next tax season for more tax education and support for PhD trainees. I offer a workshop titled How to Complete Your Grad Student Tax Return (and Understand It, Too!) during each tax season, which can be purchased by individuals or groups at a discounted rate. I’m making plans for how I can help PhD trainees with their tax returns in brand-new ways in the upcoming tax season. Join my mailing list at PFforPhDs.com/subscribe/ to stay in the loop! You can expect to receive 2-3 emails per week from me on various personal finance topics.

Before you go, would you please share this episode with your peers, especially new graduate students? Join me in helping to make next tax season go smoothly for all PhD trainees!