In this episode, Emily interviews Dr. Hannah Percival, an instructor at Houston City College who holds a PhD in music theory. Hannah shares how she financially made it through graduate school on a small stipend, including how she minimized student loan debt, side hustled, and kept her expenses low. She also tells the stories of landing her first and—more importantly—second post-PhD jobs and gives great advice for job seekers.

Links mentioned in the Episode

- Emily’s Email Address

- PF for PhDs Tax Workshops (Sponsored)

- PF for PhDs Subscribe to Mailing List

- PF for PhDs Podcast Hub

Teaser

Hannah (00:00): In general, I have found that if a department will be supportive of you, um, emotionally, they will also support you financially. And if they are going to just treat you as a cog in the machine, that will also show up in the money. So it’s okay to advocate for yourself to receive that.

Introduction

Emily (00:28): Welcome to the Personal Finance for PhDs Podcast: A Higher Education in Personal Finance. This podcast is for PhDs and PhDs-to-be who want to explore the hidden curriculum of finances to learn the best practices for money management, career advancement, and advocacy for yourself and others. I’m your host, Dr. Emily Roberts, a financial educator specializing in early-career PhDs and founder of Personal Finance for PhDs.

Emily (00:57): This is Season 22, Episode 6, and today my guest is Dr. Hannah Percival, an instructor at Houston City College who holds a PhD in music theory. Hannah shares how she financially made it through graduate school on a small stipend, including how she minimized student loan debt, side hustled, and kept her expenses low. She also tells the stories of landing her first and—more importantly—second post-PhD jobs and gives great advice for job seekers.

Emily (01:28): If you want to bring one of my live tax workshops to your university next tax season, get in touch with me ASAP! Between now and the end of the year, I’m populating my calendar, especially early February, with in person and remote speaking engagements. My workshops are typically hosted by graduate schools, postdoc offices, and graduate student associations, and sometimes individual departments. Whether you are in a position to make those arrangements or simply want to recommend me, you can get the ball rolling by emailing me at [email protected]. My tax workshops, both live and pre-recorded, are my most popular offering each year because taxes are such a widespread pain point for graduate students, postdocs, and postbacs. You can find the show notes for this episode at PFforPhDs.com/s22e6/. Without further ado, here’s my interview with Dr. Hannah Percival.

Will You Please Introduce Yourself Further?

Emily (02:40): I am delighted to have joining me on the podcast today, Dr. Hannah Percival, who is a full-time music professor and the program director for music at Houston City College. And we are gonna be talking all about making grad school work on a tiny budget <laugh>. So Hannah, I know we’re gonna get a lot of insight outta this interview. Thank you so much for volunteering to come on, and will you please introduce yourself a little bit further for our audience?

Hannah (03:02): Yes. Hi everyone. I am Hannah Percival and I have received my doctorate in fine arts in music theory and I also have a graduate, uh, certificate in piano pedagogy from Texas Tech University.

Emily (03:15): And what have you done since then? Give us a preview.

Hannah (03:19): So now I am the, uh, program coordinator at Houston City College and I’m a full-time instructor at Houston Community College. And currently this is my dream job. I love the students that I get to work with and I feel like a lot of the choices I made in grad school have prepared me super well for this position.

Minimizing Student Debt During Undergrad and Grad School

Emily (03:38): Hmm. Okay. Let’s see if we can circle back to that a little bit later. When, um, you approached me about giving this interview, you said that it was really important to you that you minimize the amount of student debt you need to take out during your PhD. So can you tell us more about what’s like normal in your program and why that approach was important to you?

Hannah (03:55): Yeah, definitely. Um, so I had a lot of emotional support and, um, encouragement from my family, but I didn’t have any financial support. Um, and so through my undergraduate degrees, minimizing debt was also important. Um, I commuted an hour and a half each way. Well, I went to community college first, um, which is one reason I have such a big passion for working at community colleges. Um, but then I commuted an hour and a half each way. Um, in order to keep working at my piano studio, I had at my parents’ house, um, for my bachelor’s degree. So I came out of the bachelor’s degree, I think that was debt free. There may have been a small, I think I took a small temporary loan for, I went on a study abroad to France for a summer and then paid that off. And so then I had a similar mindset with my master’s degree where my master’s degree is in a different field, it’s in counseling. Um, and I did the research track because I felt like it would really inform my teaching. And so that was also scholarship based because, um, as my salary as a worship leader was paid as a scholarship for this school. So minimizing debt was already really important to me. And then when I was reading up about what grad school is like, um, I saw how I was very aware of how few jobs there were <laugh>. And so even though I knew I really wanted to go to get a PhD and have that experience, I wanted to make sure that I did it in a way that wasn’t going to overly burden me in the future if I didn’t get an academic job. Um, and I think, although I probably couldn’t have articulated that at this, that this at that time, I think stability is really important to me. Even though I chose a career that’s in fine arts and in education in higher ed, um, stability is really important to me. And I think a large reason that became even more true for me during my PhD was because I had a lot of mental health and physical health issues and I realized that those can be expensive in America. And so I wanted to make sure that I wasn’t, that I was setting myself up for success even with those extenuating circumstances.

Emily (06:19): Hmm, that makes a lot of sense to me and I’m so glad that you, I mean you’re obviously very intentional throughout your entire, you know, academic journey there. I’m wondering if, um, in your field, is it typical for people to take out student loan debt and even in the program that you attended, was it typical for your classmates to be taking out debt?

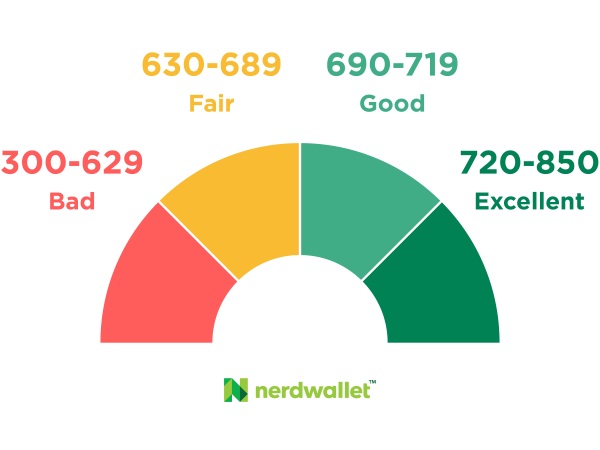

Hannah (06:38): I would say it ranges a little bit. I know that when I was looking at my career options and loans in general, my parents suggested that I sort of think about what my, i-, what would be a range of salary for what I, the career I would do and to take out no less, uh, take to not take out more than a year’s salary just as a benchmark. And I think a lot of music musicians know that the fields are not very well paying. They used to always tell us don’t go into music for the money. But I also think that musicians tend to feel very, um, dedicated and driven towards having a successful career. And so sometimes we tend to get tied up in the like prestige of needing to go to a very big university or study with a specific professor or have a specific level of instrument. And so that can also influence what you’re paying for as a musician. And I think music is an interesting cross section, especially in America where it can be a tool for people like me that felt like music was the best way to improve their life career goals. And also it’s often a very privileged, um, subset of people that are able to have those private lessons. Um, so I always hear the horror stories of people that, you know, went like a hundred thousand dollars in debt for a bassoon career and then didn’t get it into the symphony. Um, and of course those are the horror stories, but those are still real people that made difficult choices and didn’t receive the, uh, payment out that they had invested into it. So I would say there’s definitely a sub. There’s both definitely people who were more conservative about it. Um, and those were the people I gravitated towards in grad school. But there’s also definitely the pressure to don’t worry about money. You need to worry about making the best art that you can.

Emily (08:38): It’s so interesting that we’re having this conversation right now ’cause like, okay, we’re recording this in September, 2025 and you know, the, the advice that your parents give you, you know, don’t let your student loan debt exceed more than one year of your expected salary. Pretty standard. It makes a lot of sense. It’s been given for a long time. Now we’re looking at, um, you know, with the passage of the one big beautiful bill act, these overall lifetime federal student loan limits of a hundred thousand dollars for most people, and then $200,000 for certain high paid, you know, career track graduate degrees. And so I I’m imagining your track is more on that a hundred k side of things. Um, and even your example just now was that would be a, that would be a lot to take out for like this a type of career where you didn’t make it to the upper echelon of, you know, what the possibilities were. So I think this is a, a subject that’s on a lot of people’s minds at the moment and how this new, um, you know, the new rules from the federal government are going to impact borrowing for graduate degrees. Is it going to bring down the cost of programs or is it going to push more people to the private loan market or a combination of, of the two? Um, so anyway, no answers there just yet, but it makes total sense to me like why your approach to this was the way it was. And so, uh, I guess I’ll ask, did you end your PhD with no student loan debt or, you know, one year’s expected salary or like how, how did you actually finish up with respect to the student loans?

Hannah (09:59): I was looking it up right before this podcast and I couldn’t find the exact number, but I know it was no more than 13,000. Um, and I paid that off as I went. Um, I didn’t accrue that until the very end of my degree. Um, so that was right when the pandemic hit <laugh> and I had health issues at the same time, so I took out the loans for that. Um, and also something that um, I think is important is that when you receive a TA ship, you really need to look at all of the details of it and you need to know it super well and not rely on the institution or the professors to remind you of those things. And so I was aware of some of the things like I wouldn’t get paid until October so that like moving costs would be expensive, um, or not paid out until later. And I was aware of a lot of those things, but there was also in the fine print of if, you know, if your degree goes more than four years, the TA ship does not last more than four years. But nobody mentioned anything to me about that. So I was already proactive about that and had been asking around and my um, advisor realized, oh yeah, that’s a problem. And was able to find funds to keep me on as a, um, lab assistant for our research lab. But that was tricky and could have been a lot worse if I hadn’t been more proactive about that.

Emily (11:30): Wonderful advice makes, oh my gosh, I, I know there are people in the audience who really need to hear that just now. And even what you said about, um, oh, I ended up accruing, you know, most of that debt it sounds like in one year because there was a confluence effect. Okay. Pandemic, nobody expected that. And then also personal stuff coming up at the same time. And that’s actually just like on the point that I was just making about these federal loan limits, like it makes a lot of sense to have your, your plan, your like plan a for how you’re gonna fund graduate school, not to be, to be maxing out all of the loans and for everything to be going perfectly with your TAship or whatever it is to last the entire time. Because like in the course of a PhD is a long period of time and some curve balls are gonna be thrown your way. And so you need to have a little bit of room to pivot. So like you had given yourself that room by like not taking out student lending or taking it out and repaying it, you know, gradually earlier in your degree so that by the time you finished, even though you had this final curve ball <laugh>, um, you know, the overall total was really quite minimal.

Hannah (12:28): Yes. And I received a generous, um, fellowship where I, I mean it was a TA ship as well as a scholarship, so it paid all of my tuition and then fees and then I had some for living expenses. Um, so I was able to use that for the first four years and, but already I think by year three or four I had started taking on some extra side gigs and then, um, that was really helpful to utilize those when my funding, um, became less steady. And I think that one reason, I mean I, I think it took me seven years to six or seven years to finish, but um, part of that was because I was working and aut- also I chose to get an extra graduate certificate because I felt like that would really help my job chances both in academia and um, just in the professional music world. And it really did. So even though I ended up taking out some at the end, I had that flexibility because I hadn’t been using them that whole time. And it was one of the direct unsubsidized loans. And so that was very helpful because during the pandemic all of the interest was paused. So I was able to pay that off within six months, I think a year or six months. So that was very nice.

Strategically Choosing a PhD Program

Emily (13:47): Well you just brought up increasing your income and so I wanna hear more about how you did that because you described like the funding package that you received, um, but then also you were doing other kinds of side work. So let’s talk about that. But as we’re doing it, I would love for you to share also, um, because you just said it took six or seven years to finish post masters and I’m wondering if any of that, you know, extended timeline on the PhD was because you were working and what really the interplay is there between like, okay, I need more money to live, but I also need to get to graduation. So like, let’s talk about both of those things.

Hannah (14:20): Yes, definitely. Um, I think, so first of all, I think one of the best things I did was I was very strategic in choosing my graduate degree program. I saw that the funding packages for PhDs were much larger than those for master’s degrees, which makes sense. And my bachelor’s degree was in music theory and it had prepared me exceptionally well to be, to go straight into a PhD in music theory. But on paper I had a master’s degree in a very different field. So a lot of schools were not open to that, but some were very open to that. And so I had four schools that I was extremely interested in that were fine with, um, PhD students who’d had a bachelor’s degree in music but not a master’s. And they were specifically also focusing on music cognition, which was a way for me to use them, use the psychology counseling alongside with my music, um, theory. And actually I think it was my eventual advisor who helped me phrase it this way in an email of like, I think I was phrasing as a liability. And he was like, no, this is great because you have a different perspective and that can make you really unique and valuable. So, um, I had two offers. I really appreciate the fact that I invested in myself and in my future enough to pay out of pocket to go and visit both campuses. It led to some really candid conversations with students, um, and faculty at both of the institutions. And one of them, the, the institution I didn’t go to did not end up offering me that much money, but also they told me that they would try to get me in front of a classroom once before I graduated, whereas Texas Tech said that I would be an instructor on record for one or two classes every semester and I felt like that would make such a huge difference in my resume and it did actually on the job market quite a bit. And so that was really important to me. So the first thing I would do is if you have a unique situation like I do or did where you’re wanting to go into a PhD in a field that’s not directly after a master’s in your field, I would encourage you to still look at doing a PhD because any courses that you need to make up are usually going to be part of that PhD program anyway. Depends on each institution of course. But at mine it was very similar, just that the dissertation took longer at the PhD level, I would say that my degree progress was, uh, faster than a lot of my contemporaries. Um, now that I’m thinking about it, it was, let’s see, I started in 2015 and then graduated in 2021. So yeah, six years. But a, a lot of that last year and a half was because of the pandemic. My research is researching how people bond together socially over music and that hit right as COVID hit <laugh>. So my research got really changed.

Emily (17:22): I love taking it back to that selection process, um, for graduate school and that yes, you included the financial components in in the decision, but also your career progression based on your career goals. It wasn’t, you mentioned earlier about like program prestige for example, that’s important, that’s a factor, but there are other very important things as well. And so I’m really glad that you brought up those other points about like, well, is this, is this program actually gonna get me what I want in terms of the job that I wanna have after this? Like, um, it’s easy to forget that when you have all these other things that are maybe more like in your face about who do I wanna work with or like these kinds of things. So I’m really glad you brought us back there.

Increasing Your Income During Grad School With Side Jobs

Emily (17:58): So you were funded for, you know, to some degree throughout it sounds like, but then when did you bring in like outside work and how much of an impact I guess did that make on your, um, your ability to live comfortably as a graduate student?

Hannah (18:11): Yeah, so um, I think it was about year two. Yeah, I think it was about year two I started doing some extra gigs. Um, and I’ve always had multiple jobs my whole life. I think that’s just part of being a musician. So that was always sort of my plan. Um, the, the two that really were the biggest income generators and also the best for my resume were that I worked at the graduate writing center. So I got to help students, um, at any graduate program at our college, work on job documents and work on their uh, projects. And it was very interesting because get to talk to all these people from different fields and uh, I also got the opportunity to practice teaching writing, which I feel like is a really important skill within music research that’s not often taught. And then I was a, um, teaching artist for the Lubbock Symphony Orchestra. So I would go into classrooms in public schools and teach, um, music for second graders about their science curriculum or about their um, political science curriculum. So that was very fun. Both of those were very fluid as far as I could schedule them when I needed to around my classes and my TAship. That was very helpful and would have been very difficult to do a different, um, a different type of work that wasn’t more flexible. Um, I also did two like tutoring accompanying piano lessons. Those were sort of like the black market or like kind of just did it without on my own gig work. Um, and then during the off times, um, sort of an inverse where Lubbock is very isolated and so at Christmas time if I stayed in Lubbock I could make a lot of money as a pet sitter and doing gigs by playing music at Christmas. But for the first two years in the summer it the, all of the college students tend to leave. And so my little bubble really, really would collapse economically. And so I actually went back home to live with my parents for two summers so I could work at a local bookstore and then actually pay for my rent during those months. After a few years then I was able to do some more of the writing at uh, working at the writing center during the summer and working with um, Lubbock Symphony during the summer. But my first two years I actually went back home first.

Emily (20:36): I love all these ideas, all these creative ideas and some of them of course are unique to you and the skills that you were developing, you know, during graduate school and some of them are things that probably other people could do as well. Well, um, I like that you had that like observation about the town emptying out at certain times of year and how that affected you. And certainly if you live in a college town then uh, you have to take into account those cycles. Um, so interesting. Okay. Is there anything else you wanna add about increasing income or side? Actually I do have one more follow up question. Um, you mentioned the writing center job and that it was, um, you could schedule it around your, you know, the volume of work that you had going on elsewhere. That’s really cool. ’cause I would’ve thought that a writing center job would be sort of like an assistantship, like a regular certain number of hours per week. So can you explain to me how that job was different than like your TA type position?

Hannah (21:28): It was a certain number of hours per week, but because we were working with um, graduate students, a lot of graduate students preferred evening hours and so I was able to schedule most of my writing sessions or you know, client sessions in the evenings. And I think for a while we may have even done Saturdays online, I can’t remember, but I remember that they weren’t just during the nine to five, so that was very helpful.

Emily (21:55): I see. And I love jobs like, well I’m using the word job a little bit loosely, but work that graduate students can pursue that they can schedule around what works for them because your primary focus is getting through that dissertation and doing the research that you need to do. And so yeah, there are certain times when your source of income is gonna have to take, you know, a back seat and you still want it to be there for you and you’re ready to, you know, have a different schedule, put more hours into it. So that’s very, very helpful when you can find that kind of work.

Hannah (22:25): And I found it actually very, um, motivating for finishing my degree because everyone was working with graduate students who were trying to work through their own dissertations and a lot of the, about 50% of the staff were grad current graduate students. And so it was also encouraging to be in a group of people who were currently writing and going through that process. Um, while there were a lot of people doing things like music musicology, um, or music performance, there weren’t that many people who were doing a music PhD when I was. And so I sort of had to build my own little cohort and doing the writing center really helped. And it was also nice to do it in a group that’s not your own field. Sometimes it’s, it’s nice to connect with graduate students that are not just with your same professor and same classes but still have similar experiences that they’re going through.

Emily (23:19): Absolutely. This is an important part of like side work that often goes overlooked, which is the networking. Like it can, in your case it helped you find people who can motivate you to get to your finish line in terms of your PhD or you know, there’s other purposes in other settings of course. Anything else you wanted to add about the income side of the equation?

Applying for Small Scholarships and Career Planning

Hannah (23:36): I encourage people to apply for small scholarships that seem really relevant to what they need for the same reasons you just mentioned. Um, you know, it’s free money <laugh>, which is awesome. Um, and you also build those networks that are super helpful for in that moment, getting to know people that are interested in your field and also it adds to your resume. It’s another thing you can put on it, uh, that helps you gain more scholarships. So I know some people, um, in the past used, like I had an advisor in undergrad encourage me not to apply for small scholarships because it wasn’t worth the time. But I have found them very helpful.

Emily (24:15): I’m so glad that you added that. Yeah, I mean applying for scholarships too is one of, I’m, I’m really surprised that your undergrad advisor said that because I feel like the attitude generally is like you’re gonna be preparing a lot of materials for a lot of different purposes anyway. And so like yes of course you have to tailor and you have to be selective, but I don’t know that the time burden is that much and winning it really can help you, not only monetarily but also in all these other factors that we were just talking about. So like, yeah, I’m glad you kind of <laugh> moved on past that advice and said, okay, I’m gonna go in a different direction.

Hannah (24:48): I think that it’s also really important when you’re in the bubble of grad school to be thinking about multiple different careers you could use, um, postgraduate school and part of that is looking to see what are the most, where will my skills be most used? So also what you love and also what you’re good at. But I think sometimes in music we often prioritize what we love or what we want to do, but I think there’s a lot of benefit in also seeing what will be the most required of me in a field. So I realized that all music, all bachelor’s degrees in the US um, tend to require four semesters of music theory, four semesters of sight singing and ear training, and four semesters of class piano. And so I felt like focusing on those were really great, um, job security and so I pursued some extra the, the extra certificate and I have found that to be extremely helpful. ’cause those are sort of the like bread and butter of the degree plans and then if you have extras that you can add on, that’s great, but being able to fill in where it’s most, um, there’s a significant need for those courses can be really helpful.

Emily (26:09): Yeah, I mean kind of what we were talking about earlier about like, oh plan a, like plan A might not work out and it’s helpful to have some skills that are going to apply. So you have a plan B and a plan C and so forth. Um, very, very smart.

Commercial

Emily (26:22): Emily here for a brief interlude! I’m hard at work behind the scenes updating my suite of tax return preparation workshops for tax year 2025. These educational workshops explain how to identify, calculate, and report your higher education-related income and expenses on your federal tax return. For the 2025 tax season starting in January 2026, I’m offering live and pre-recorded workshops for US citizen/resident graduate students, postdocs, and postbacs and non-resident graduate students and postdocs. Would you please reach out to your graduate school, graduate student government, postdoc office, international house, fellowship coordinator, etc. to request that they host one or more of these workshops for you and your peers? I’d love to receive a warm introduction to a potential sponsor this fall so we can hit the ground running in January serving those early bird filers. You can find more information about hosting these workshops at P F f o r P h D s dot com slash tax dash workshops. Please pass that page on to the potential sponsor. Now back to our interview.

Housing and Transportation Choices That Kept Expenses Low

Emily (27:40): Let’s talk about the expenses side of the equation. The other half of like making it work financially as a graduate student. So were there any like, um, either really valuable or like really creative, um, things that you did to um, keep a lid on your expenses during graduate school?

Hannah (27:56): Yes, I was also lucky in that Lubbock is a very low cost of living area. Um, and I know that that’s not always true. That’s definitely something I also took into account before moving. Um, but one thing I did, I took a lot of searching but I found a really cute, um, duplex or more like a quadruplex but little apartment that was within walking distance. It was a long walking distance but walking distance. So I didn’t, ’cause I didn’t have a car for the first three years, which is another reason why I didn’t really have any jobs until side jobs until year two or three. So I couldn’t really leave anywhere that wasn’t campus. Um, so that really kind of limited things and I thought it would limit my social life, but I’m also kind of introverted anyway and I found people that were willing to like pick me up to go to a board game night and things. So I, I didn’t find it to be a huge sacrifice unless it was a, a windstorm then that was rough.

Emily (28:57): Okay. So is the sort of frugal tactic there the place where you lived or is it the living in such a place that you didn’t need to own a car?

Hannah (29:05): I think a combination. So if I had lived in a town that had really good public transportation, then that would also save me a lot of money. Um, Lubbock is not known for being a walking town, so I was lucky in that I was able to find a place close to campus that was reasonably priced. So I think it was a combination of realizing that Lubbock did not have good public transportation and I wasn’t going to have a car. So making sure that some of like the money that I would’ve paid for a car went more towards the um, rent. So I think that my rent was 750 a month, which was really nice.

Emily (29:50): Hmm. And you said something like it was a difficult search process. Like can you give us any tips what you think might be applicable for other graduate students? Because I, I’ve heard this kind of over and over on the podcast is like I really had to put in legwork, but I found a deal.

Hannah (30:06): Yes. My mom and I drove down to Lubbock and we talked with a, uh, realtor, well actually we talked with two or three realtors and we went and looked at several different properties, um, that were all within walking distance of the college and two of the like realtors we talked with, it just wasn’t a good fit. And the, the location one place we looked at the ceiling like I would not have been able to stand up in the apartment for my entire, you know, college degree <laugh>. Um, and so we were supposed to go back to uh, back home but we still hadn’t found a place to live so we ended up staying an extra day and continuing to look at other um, properties and we finally found one that was nice and um, but it took a lot of searching. So I think knowing what your like, um, most important things are, which mine was walking distance to school, I was good and I ended up spending a little more than I wanted but it was, oh and I wanted it to be safe. So, but then that also meant I had to compromise on other things. Like the laundromat was in the, um, the laundry was in the garage and um, I don’t think there was no central heating and things like that. So.

Emily (31:27): I see. Well can I ask then about, it sounds like at some point you acquired a car and what the sort of trade off was there because you also mentioned well that enabled me to do different kinds of work.

Hannah (31:39): Yeah, so again, lucky, I was lucky in that um, through an inheritance my parents were able to buy me a used car and so the car um, helped me go and do more gigs. And so that was really nice because it was able, you know, I didn’t have to pay for the car payment. So that was a big blessing and it helped me to be able to go do more gigs throughout Lubbock.

Emily (32:03): But you have to pay for insurance, you have to pay for gas. You have to pay for registration. So like there are, aside from just definitely the cost of the car itself, there’s other like expenses. But it sounds like it was worthwhile, right?

Hannah (32:14): Yes, yes. Yeah, it was for me.

Emily (32:16): Alright. What other frugal tactics did you use?

Using Free or Low-Cost Campus Resources

Hannah (32:19): I tried to use as many of the campus resources as possible. Um, so we had a food bank and um, I was able to use counseling services there and um, at one point I used medical services on campus and then I realized that our student health insurance, I mean the insurance that I got through being a TA was good enough that I could go outside of campus and receive a little bit cheaper and better care. Um, but always looked for all of the free food options and go to all of the different like talks that had free food.

Emily (32:53): Can I ask about the food bank usage? Because I know some students have certain feelings about accessing basic needs like that, but like how did you think about that?

Hannah (33:03): I ended up not using it as much as I could have because I, I don’t know why, honestly, I think I had this idea of like, well I’m good enough, somebody else can use it.

Emily (33:14): So you had certain feelings about it too.

Hannah (33:15): Yeah. But if everybody feels that way, um, but I know it was just really helpful for my mental health to know that it was there if I needed it.

Emily (33:23): This is actually something that came up, um, in an interview that I’ve not published yet, but that will be coming out before, before this current interview is coming out. And that’s about actually looking, we were talking earlier about the selection of graduate school, um, taking into account the student services that are provided at the different options that you have in particular basic needs. And we were talking earlier about plan A for, you know, your funding during graduate school. Hey, it’s really great to know if there are basic needs services available on campus, even if you don’t plan on using them. Like you said, just knowing it’s there as a backup option can be really, really helpful and comforting. And so, you know, if you hit some, some skids that like, okay, like that’s there for me, I’m not going to be food insecure.

Hannah (34:04): Yes, yes, definitely. I um, I think my biggest expense with the medical bills, um, so that was a frustrating thing, but it was really nice that we did have good health insurance, um, through being a ta. Um, yeah, I really wanted a kitty, but I waited because I was like, what if the kitty has health problems and I can’t take them to the vet? And then that ended up being um, a good thing. I adopted a kitty, um, during the pandemic. I couldn’t wait any longer. Um, but then um, he ended up having some pretty severe diabetes complications, but by then I had already had a stable job and things. But I’m proud of younger Hannah for not getting a cat then even though I wanted it because I think it was, it did end up being much more expensive than I expected.

Emily (34:58): Yeah, you were prescient in that way actually. And yeah, I mean if you’re struggling just to provide for yourself, then yeah, you definitely have to think twice about adding anyone to your household in that sense. Was there anything for other people who really want to be pet owners <laugh> while they’re in graduate school, uh, but maybe think the same as you, it’s, it’s not the right time financially. Like were there ways that you could get some of the same benefits of having a pet that um, that you know, before you actually could adopt one

Hannah (35:26): Highly recommend being a pet sitter <laugh> because yes, you get all of those cuddles and you get paid for it.

Emily (35:33): Yes. Um, I just put this in the sample chapter for my book that I’m writing, which is like, uh, about increasing income and saying how like baby pet and house sitting, hey, like if you get some personal joy out of those like scenarios and you get paid for it, like double benefit.

Hannah (35:49): Yes.

Transitioning From Grad School to Full-Time Employment

Emily (35:51): Let’s talk then about when you transition out of graduate school and we’re applying for full-time positions. Um, do you have any other advice for people who are in like a similar stage or leading up to that stage?

Hannah (36:03): Yes. One is more generic that I think people hear a lot, but I think is still important. At the graduate writing center I learned a lot about helping to really tailor your documents to the job ad and to um, also for funding if you’re applying for a specific type of grant or funding. And I found that extremely useful not only for um, you know, getting an interview but also for understanding is this a job that I want? Is this the type of opportunity that would be good for me? Am I good match for this? Um, but I will also say that even when you tailor everything and you work really hard on your applications, it’s still very confusing. And having now been on some job searches, it’s also very confusing. Like the whole process is confusing for the applicants I think because you don’t get a lot of feedback on what you did wrong or right. Um, and there’s a lot of luck involved of like, are you the specific candidate that that person needs at that specific time and they may have needs that they haven’t been able to like, um, advertise exactly. So I think being kind to yourself during the job hunt is very important because there’s a lot of luck involved unfortunately. Um, and I applied to hundreds, um, over many years. I got about 10 initial interviews, um, and I only got, well, I guess I only got one on campus interview, so there weren’t very many on campus interviews. Um, but I really felt like it was still important for me to do that process and to continue trying for that. During that time I was continuing to work at the graduate writing center and I taught piano lessons, um, but I started rewarding myself with, um, every rejection letter I would get, whether it’s for a, a funding opportunity or a job, I would buy myself office supplies. So I had so many fancy pens for a while.

Emily (38:14): Yeah, I mean at least when you were receiving that bad news, you can say, oh but I get to buy something really pretty from my desk. That’s nice. Um, so it sounds to me like that you finished graduate school, you were doing this sort of part-time work, um, while you were continuing to apply for full-time positions. Is that right? Okay. And I think your advice is very good, very spot on. But like, is there anything more that you can say about that perseverance, because that’s a lot of applications that you had to submit.

Hannah (38:44): Yes, it was, I, I wanna acknowledge that I did get married during that time and it was to someone that had savings and had a steady job and that was really wonderful. It was also really important to me that I have the career that I had worked so long for. So I, um, could have certainly built up my piano studio and done taken on more writing clients, but I really wanted to try to be the co- a college professor since I had worked for that for so long. So I got an opportunity to teach at a school and it was teaching all the things I wanted to during the interview, it seemed like it was going to be a great fit where I could really help students and it was in a small environment. So we moved and thankfully my husband’s job is remote so he was able to move with me. Um, but I got there and I had already had some health issues and I let them know before I came that I was going to need a sub for the first two weeks. So before I accepted the job, I let them know and they were okay with that. Um, but then when I got there, they hadn’t gotten any subs for me and then they were upset that I hadn’t been more dedicated to my students even though I was on bed rest for my surgery. And so it quickly became very toxic and it got to the point where after about eight weeks in that job, I found myself very jealous of people in the grocery store, like workers in the grocery store because I was like, they’re able to do their job and go home and be done and they don’t have to worry about am I harming this student’s future? Am I helping the student take on so much college debt knowing that they’re not going to be successful in this program? So I reached out to my PhD advisor and he was very encouraging saying that, you know, I was more important than the job title and that if I ended up leaving and doing my plan B or C or D that was more important than letting the job and the toxicity of that job wreck my mental health to irreparable spot. So while I was teaching full-time at that institution, it was $24,000 a year for full-time, which is not enough to survive on. So I was also adjuncting for Houston Community College at the time, um, online. And everyone I knew who was at that level working had to do two jobs at once. Um, whether it was teaching at more than one institution or some other kind of job. And that actually gave me, um, the job that I have now. So it was a really good learning experience to realize that I can be good at this job and I can love it and I can still be at the wrong spot. So to realize that sometimes you can have your dream job and it’s not the right environment and to be willing to walk away from that is hard, but sometimes it can lead you into more healthy positions. Um, and the position I’m in now, I feel very supported. My colleagues are wonderful. I still get to help support students and I feel like I am being supported for the long haul. So I just want to encourage people that if your your dream job turns out not to be your dream job, that’s okay.

Emily (42:24): I’m taking two things from that story and I’m so glad that it took the turn <laugh> that it did. Um, the, the first is that the long protracted search for the first job did not have to be repeated, right? It was much more ready that you got the second job, um, even though the first one took so long to land.

Hannah (42:42): Although, although I did do, um, I was applying to even more jobs with the full-time in order to get out of that position.

Emily (42:49): Yeah, that makes sense. But it didn’t take the length of time that.

Hannah (42:51): Correct.

Emily (42:52): You know, the first one took, um, and the second one was that opportunities came from working. So.

Hannah (42:57): Yes, absolutely

Emily (42:58): Just, just doing anything that’s, you know, related. I mean as related as it can be of course to the career that you ultimately want, but like just doing any kind of work in that field is going to be helpful to you in some manner. And it, I hear this story over and over again of like the part-time work I did or, you know, it led to that full-time job. It happens over and over, it makes sense. People wanna hire known quantities of course. So I just wanna point that out as well as like keep working <laugh>, uh, even side work, uh, in addition to the full-time job. If, if you’re not, if the full-time job is not everything that you know it cracked up to be, then keep creating opportunities for yourself through working and of course continuing to apply as you did. So I find that very encouraging. Um, anything else you wanna share with our audience? You know, advice for getting that first job or the second job post PhD?

Hannah (43:51): It’s okay to want stable income and I think that that’s not always talked about in music. I, it’s we’re told to follow our passion and I’m lucky in that I did find the job that I wanted all along and um, you know, it’s got a really nice bow on the story, but I also know a lot of people that have happier lives outside of academia that are, have the space now to do things that they’ve wanted to do in their artistic field. Um, but in general I have found that if a department will be supportive of you, um, emotionally, they will also support you financially. And if they are going to just treat you as a cog in the machine, that will also show up in the money. So it’s okay to advocate for yourself, um, to receive that. And so when I went over to this full-time position, um, I ended up making three times the amount of money for like half the work. And so I also encourage people, um, to consider highly consider, um, working at a community college. Um, especially if you have a passion for teaching. It doesn’t have the prestige as some other places. Um, and some places have a little bit of a stigma because you often are not paid to research, you’re not, your research is not the important part, but there’s a lot of funding available. And so a lot of the professors that have the most lucrative jobs I know tend to work full-time at community colleges.

Emily (45:26): I actually have, um, a neighbor where I live who has a PhD and teaches at a local community college. And I, I believe it has the same kind of tenure system. Obviously it’s not based on the same things that it would be at an R one institution, but there’s still a great deal of job security that can be attained through this route. Which as you said earlier, is one of your high like values. Hannah, thank you so much for this interview. It’s been, it’s been very encouraging and yes, I’m so glad that you volunteered to give it.

Best Financial Advice for Another Early-Career PhD

Emily (45:55): Would you please share with us your best financial advice for another early career PhD? And it could be something that we’ve touched on in the interview already or it could be something completely new.

Hannah (46:03): Yes. I was brainstorming how to phrase this with my husband ’cause it was this big complicated thing and he said, um, don’t get academia tunnel vision. And I loved that phrasing because in academia we tend to have these ideas. If you do this and then you do this, and if that doesn’t work, you just keep trying. And that if, if you have to move your family to a place they don’t want to be, you do it or you take the place that has the best prestige. And I have found that it is good and healthy to prioritize your own mental personal stability. And sorry, I messed that up, <laugh>, that it’s good to prioritize your own mental health and physical health and stability. You get to choose how you work for academia and you get to choose if academia is placing you into a position that is untenable, it’s okay to do plan B or plan C.

Emily (47:06): I love the phrasing that your husband came up with. I love your phrasing that you had just there. You choose how you work for academia. Like this is a two-way street ultimately. And we’ve seen so much with, um, I, I mean this is going on for decades now but the quit lit like people make, you know, they think that academia is the be all end all and then realize that it’s not and they end up leaving for, you know, greener pastures and so forth. And just great advice. I want people to go back, listen to that little segment over again because it’s so, so true and we all need to hear it more. So thank you very much. Um, and thank you again for volunteering to give this interview.

Hannah (47:40): Thank you so much and I appreciate all of your work Emily, your, um, work on, um, the tax preparation was so helpful, especially because understanding how taxes work for things that are both stipend but then also a paycheck are very like very confusing. So I really, really appreciate you and so does my tax returns.

Emily (48:00): Okay. Thank you so much for saying that.

Outro

Emily (48:12): Listeners, thank you for joining me for this episode! I have a gift for you! You know that final question I ask of all my guests regarding their best financial advice? My team has collected short summaries of all the answers ever given on the podcast into a document that is updated with each new episode release. You can gain access to it by registering for my mailing list at PFforPhDs.com/advice/. Would you like to access transcripts or videos of each episode? I link the show notes for each episode from PFforPhDs.com/podcast/. See you in the next episode, and remember: You don’t have to have a PhD to succeed with personal finance… but it helps! Nothing you hear on this podcast should be taken as financial, tax, or legal advice for any individual. The music is “Stages of Awakening” by Podington Bear from the Free Music Archive and is shared under CC by NC. Podcast editing by me and show notes creation by Dr. Jill Hoffman.